“Jeju 4·3 was my destiny”: A path of devotion for half of life

Resolution of Jeju 4·3: Achievements and Contributions

“Jeju 4·3 was my destiny”: A path of devotion for half of life

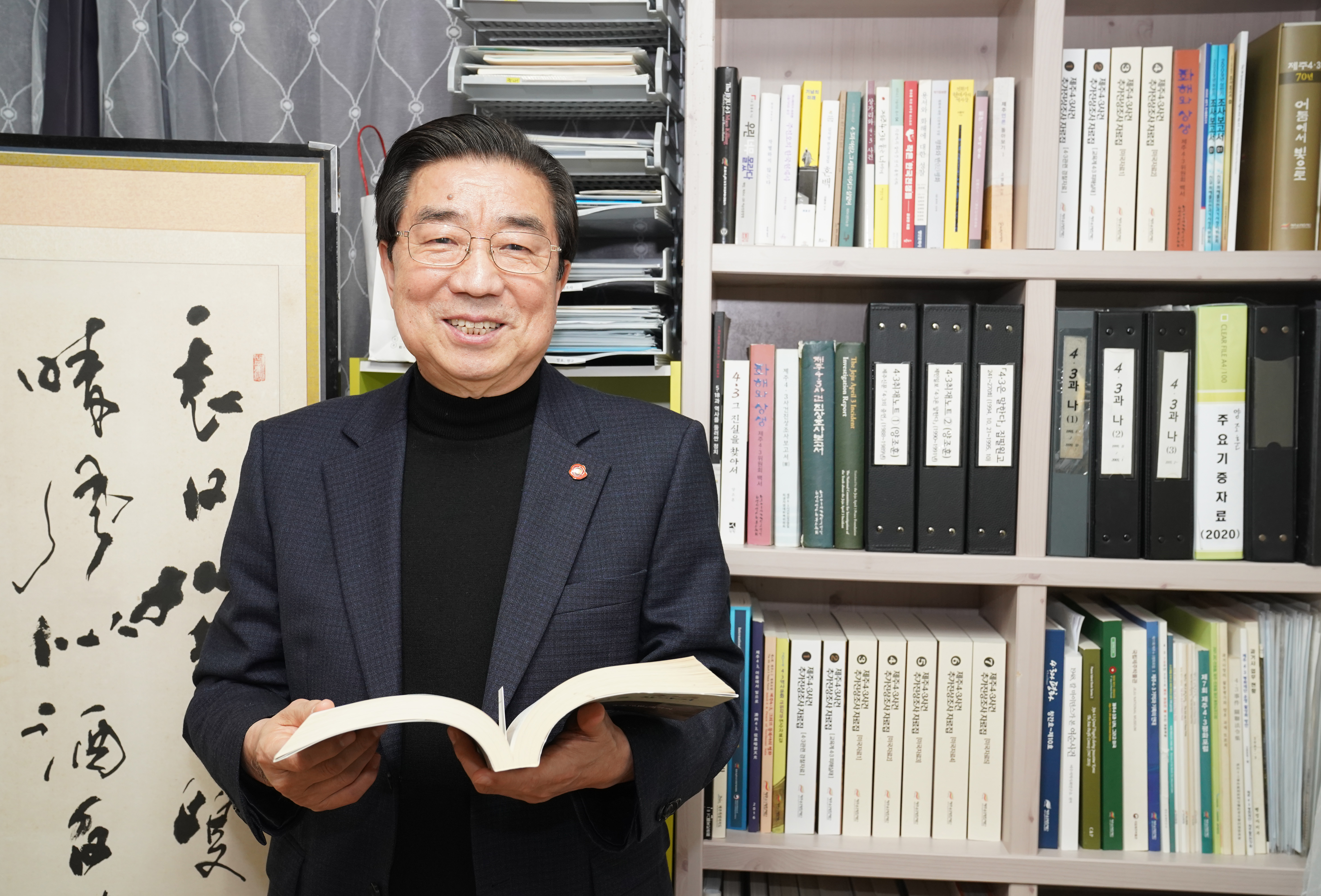

Yang Jo Hoon, former president of the Jeju 4·3 Foundation.

Yang Jo Hoon was born in Jeju-eup in December 1948, when the turbulence of Jeju 4·3 swept over the entire island of Jeju. He studied at Jeju National University’s Department of Korean Language and Literature and then at Dongguk University’s Graduate School of Public Administration. He worked as a journalist for 27 years from 1972. In 1988, he was appointed to head Jeju Shinmun’s 4·3 Coverage Team and published the series “Testimonies of Jeju 4·3.” This is how he had a fateful encounter with Jeju 4·3. Afterward, he led the Jemin Ilbo’s 4·3 Coverage Team and then as its editor-in-chief, issued a series titled “4·3 Speaks” over 10 years to reveal the truth of the tragic event. After being dismissed from the newspaper in 1999, he led the campaign to enact a special law on Jeju 4·3 by serving as a co-representative of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act Legislation Solidarity. Starting from 2000, he participated in authoring “The Jeju April 3 Incident Investigation Report” as a senior expert member of the Jeju 4·3 Committee. Using this investigation report, he played a pivotal role in achieving a presidential public apology for the victims, a first in Korean history.

He served as the first executive director of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, the environmental vice governor of Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, and chairman of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Education Committee of the Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Office of Education. His writings include “4·3 Speaks” (five volumes, co-author, 1994-1998), “Jeju 4·3” (Japanese, six volumes, co-author, 1994-2004), “Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report” (co-author, 2003), “Reconciliation and Mutual Prosperity: Jeju 4·3 Committee White Book” (co-author, 2008), and “In Search of the Truth of 4·3” (2015). For his contributions to media, he won the Songha Press Award, the Korean Journalist Award, and the Jeju Culture Award. In 2019, he received the Asia-Pacific Coordination Forum (APMF) Peace Prize for his contributions to discovering the truth of Jeju 4·3.

Novelist Hyun Ki-young referred to him as “a person who has lived for half of his life, to tell the truth of Jeju 4·3 and whose name became a symbolic byword of the Jeju 4·3 movements.” By heading the 4·3 coverage teams of local newspapers, he locked himself in the prison of Jeju 4·3, spending his days discovering the truth of Jeju 4·3. He calls the journey he has taken for Jeju 4·3 his destiny. One would easily collapse when drawn into a whirlpool of a complicated movement such as the one related to Jeju 4·3, but he persevered through the difficulties with precision. Looking back, the efforts to reveal the truth of Jeju 4·3 have relied on the former journalist. His book “In Search of the Truth of 4·3” depicts how he walked along the dangerous path of Jeju 4·3. In January, he completed his four-year term as president of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation. I was curious about his achievements that have become the foundation of the movement to reveal the truth of Jeju 4·3, as well as what steps he would take next. — Editor

Interview and arrangement by Huh Young-sun, director of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute

Photography by Kim Yeong-mo, member of the Memorial Project Team

I found your retirement address to the victims of the bereaved families impressive. How have you been since retiring? It is doubtful that you are free from work because of your diligent personality.

These days, I’m having the most relaxing time of my life. The day passes quickly when I read books I used to put aside

to read later and organize the materials that I have collected. I’m also thinking of authoring a book about Jeju 4·3 that

will be easy to understand.

At the Jan. 21 farewell ceremony, I asked the bereaved families for a favor. It was concerning the compensation for the

victims. I stressed that the money issue should not cause new conflicts among the family members. I asked them to

show the potential of the bereaved families so that the legitimacy and authenticity of the compensation would not fade.

It feels like Jeju 4·3 has overwhelmed half of your life. I sometimes wonder if it was the souls of the victims that attracted you to get involved. What does 4·3 mean to you?

I often say that it was destiny. I was born in December 1948, when the 4·3 craze was in full swing, but none of my

family members fell victim to it. In 1988, when I was 40 years old, I happened to head a 4·3 coverage team. Should I

say that I was caught up in the democratization fever brought on by the 1987 June Struggle? There were times when I

was so scared that I tried to escape. After suffering from nightmares, I finally made up my mind to continue the work

that has carried me to where I stand today.

I left the Jemin Ilbo in 1999. My series covering Jeju 4·3 were also suspended. If it hadn’t happened, I would have

served as the CEO of the newspaper for some years. As I was dismissed, I eventually participated in the movement to

enact a special law on Jeju 4·3, after which I took a completely unexpected path, such as serving as a senior expert

member of the Jeju 4·3 Committee. Experiencing several encounters with the spirits of Jeju 4·3 victims, I thought,

“Jeju 4·3 is my destiny.”

[Yang Jo Hoon (left) is being interviewed by Huh Young-sun.]

Taking on a range of posts, from the head of the 4·3 coverage teams, the co-representative of the Jeju 4·3

Special Act Legislation Solidarity team, a senior expert member of the Jeju 4·3 Committee, and the president

of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, you have been in the middle of the movement to reveal the truth of Jeju 4·3

and made a lot of achievements. There must have been some difficult moments in the process.

The most difficult moment was when I joined the Jeju 4·3 Committee as a senior expert member after the enactment of

the Jeju 4·3 Special Act in 2000. I experienced a lot of conflict with the administrative support team while leading the

truth investigation team. When I delivered to the administrative support team the various complaints filed by the

investigation team, they were negative about everything, saying, “There is no precedent.” In fact, there was no

precedent because it was the first time the government investigated the past. Without realizing it, I became stuck

between the investigation team and the administration team. Every day was a tough day.

The other is the situation right after “The Jeju 4·3 Investigation Report” was passed. The deliberation process of the

report was very difficult to manage. I took the matter on as if it were a matter of life or death. When the report was

finalized, however, the pro-investigation blocs rather disparaged the report as a “half-report” and announced that they

would issue a “real white paper.” I felt somewhat empty. Having lost all my energy, I even felt frustrated with myself,

asking “Why did I do this?”

This may be the same question, but when did you feel satisfied and proud while revealing the truth of Jeju

4·3?

It was in December 1999, when the Jeju 4·3 Special Act was passed at the National Assembly. During the National

Assembly sessions, the draft bill had only the body of its provisions, with the provisions that should have served as its

arms and legs having been cut off. There were only 11 clauses left. Civic groups, of course, opposed it, arguing

“There’s no need to legislate this nonsense.” However, Rep. Choo Mi-ae persuaded them, saying, “It would be easy to

revise the law once it is enacted.” Hearing that if we missed the opportunity, we would have to wait another four years,

I took the lead in passing the “shabby” Jeju 4·3 Special Act. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the

unsatisfactory special law created the status of Jeju 4·3 of today.

I was happy when “The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report” was adopted by the national government, but the more

touching moment was when President Roh Moo-hyun officially apologized according to the report’s conclusion. That

was when I cried.

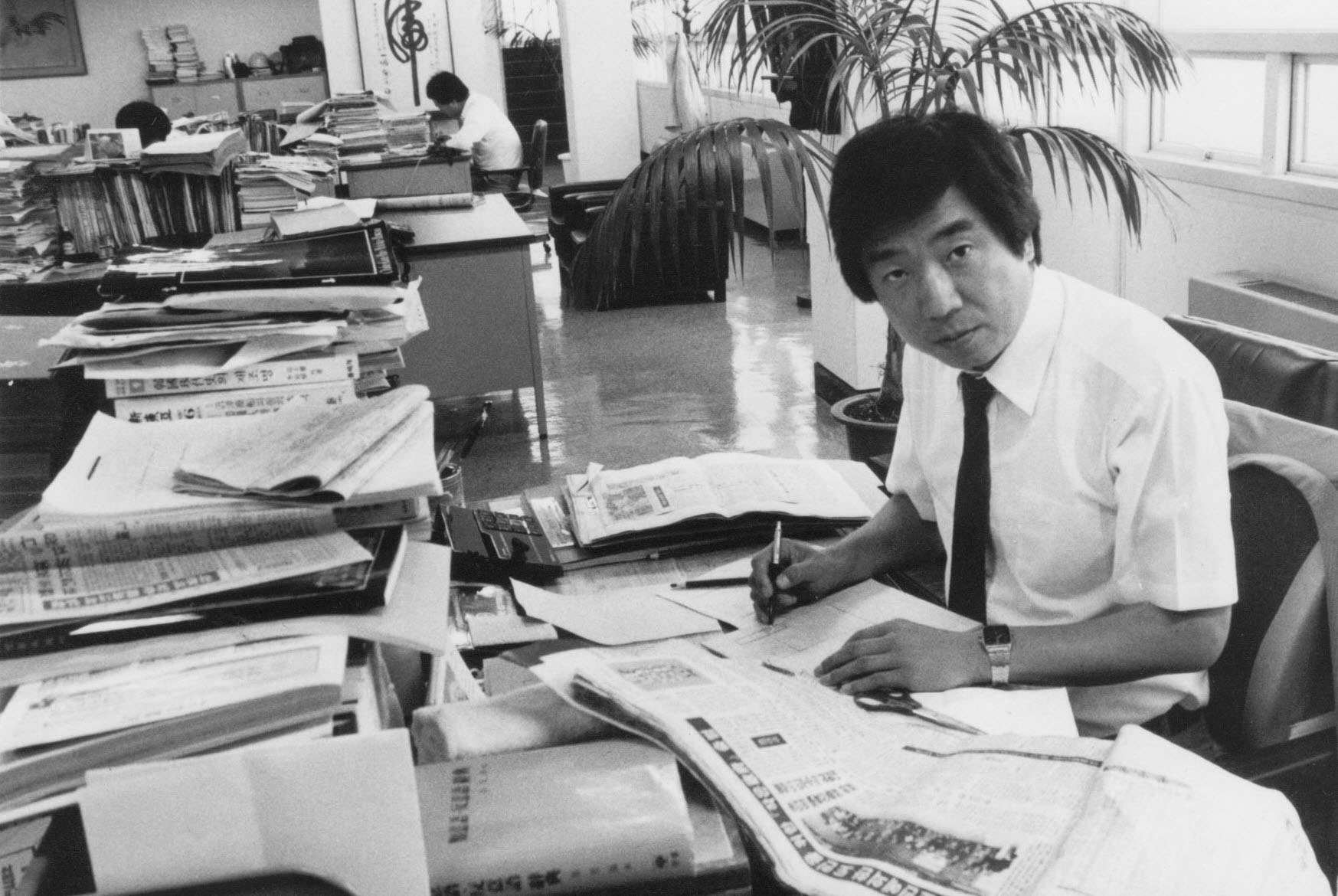

[Yang Jo Hoon working in the Editorial Department while heading the 4·3 Coverage Team of the Jemin Ilbo in 1992.]

The long-term series, which started with “Testimonies of 4·3” of the Jeju Shinmun and ended with “4·3

Speaks” of the Jemin Ilbo, were issued in a total of 513 articles. These articles not only laid the foundation for

the revelation of the truth of Jeju 4·3 but also created a legendary record in Korean media. Could you

introduce what you focused on at the beginning of the project?

I started covering Jeju 4·3 in 1988, but elderly men and women who experienced the tragedy rarely spoke. I managed

to persuade some of them to be interviewed, and when I was about to end the interview after only hearing a few

words, they used to hold my hand tightly and said, “Please get rid of my false accusation of being a communist.”

That’s why I decided to reveal the truth concerning the claim that Jeju 4·3 was a communist riot. While conducting in-

depth coverage of the arson of Ora Village and analyzing the posthumous writing of the 9th Regiment Commander Kim

Ik-ryul of the National Defense Guard (NDG) — which was difficult to collect — my team found traces of manipulation

by the U.S. Army Military Government and the police. Lieutenant Lee Yoon-rak, a former intelligence officer of the NDG

9th Regiment who had participated in the peace negotiations with the armed resistance forces, also gave us a very

helpful on-site testimony.

At the time, the writers from conservative blocs cherished the writing by Park Gap-dong, underground chief of the

South Korea Labor Party, which reads, “There was an order for a riot from the Central Party.” But when we analyzed

his documents, there were many distorted and sloppy parts. We heard from Park Gap-dong, who lived in Japan, a

shocking answer that “the document was not my writing, but was rewritten by an intelligence agency.”

Until the late 1980s, high school history textbooks described Jeju 4·3 as a riot that took place under the North Korean

communist mantra. We traced the textbook authors. But they responded in a ridiculous way that they didn’t do the

research on their own but just cited existing materials. So, we reported the fiction of the textbooks as a top article, and

reporter Kim Jong-min played a key role.

The coverage of Jeju 4·3 eventually traced responsibility to the United States. Based on your research

experience of 30 years, what do you think is the relationship between Jeju 4·3 and the United States, and what

would be the issue of U.S. responsibility for Jeju 4·3?

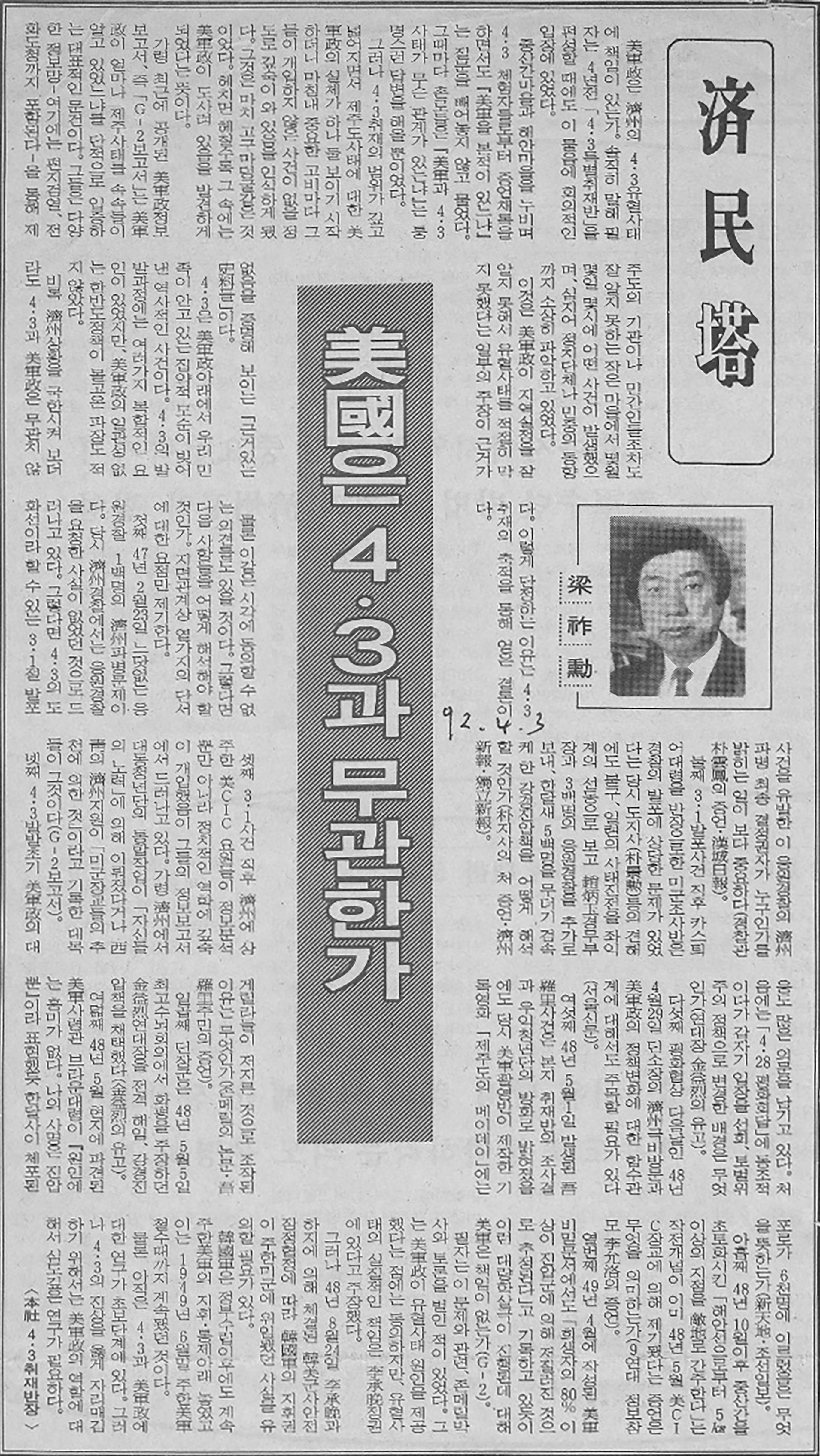

I had a special experience in 1992. In April of that year, I wrote a column, titled “Is America irrelevant to 4·3?” Soon

after, an American Cultural Center official contacted me and suggested that I interview Dr. John Merrill. Merrill received

his master’s degree in 1975 from Harvard University for his research on Jeju 4·3, and he was working as an official at

the U.S. Department of State when I wrote the column. When I agreed to interview him, a triangular satellite relay

system was installed to connect him from Washington, an interpreter from Virginia, and me from Jeju Island.

Merrill’s argument was dichotomous, saying, “The USAMGIK also did wrong in terms of the cause of the Jeju 4·3

outbreak, but the Rhee Syngman regime should be held responsible for the massacres.” So I countered that the

Korean Military Advisory Group (KMAG) of the U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) is largely responsible because it held the

right to operate the Korean military forces. The problem is that a first-class U.S. Department of State interpreter was

mobilized for the interview. The interpreter was experienced and skilled enough to interpret for the ROK-U.S. summit.

In the end, it was the first and last time that the U.S. Department of State engaged in the 4·3 issue.

Clearly, the U.S. was involved in the Scorched Earth Operation during Jeju 4·3. The representative figure is General

W. L. Roberts, the then-head of the USFK KMAG.

[The column “Is America irrelevant to 4·3?” on the April 3 issue published in the Jemin Ilbo in 1992]

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the excavation of the remains of Darangshi Cave. The Jeju 4·3 Research Institute discovered the cave and opened it to the public along with the Jemin Ilbo. As far as I know, there were many regretful moments during the exhumation of the remains. How do you feel about the 30th anniversary?

I believe that the intelligence agency intervened, cremated the remains found in the cave, and scattered them into the sea to remove traces.

There was a man surnamed Ko, who claimed to represent the victims’ families at the time. Even though he was not a legal bereaved family member, he lied that a victim’s son entrusted him. It is inevitable to view that the administration joined the cover-up according to his claim.

If there is something that comforts me, it would be a replica of the Darangshi Cave is now available in the Special Exhibition Room of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Memorial Hall. Additionally, we promoted the excavation on a global scale through articles published by the Yomiuri Shimbun, and videos and booklets were produced in Korea. It is also a bit comforting that the relics have not been destroyed and are still preserved in the cave.

After leaving the newspaper, you actively participated in the campaign to enact the Jeju 4·3 Special Act by taking the post of a co-representative of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act Legislation Solidarity. You once described the passing of the bill as a “miracle-like moment.” Why did you use that expression?

Oh, that’s right. It was under the Kim Dae-jung administration, but the opposition party was the majority in the National Assembly, having a lot more lawmakers from the Grand National Party (GNP). It was an excellent idea that Jeju-based GNP lawmakers made a proposal to enact the special act. It would have been difficult if it were the other way round.

At that time, the ruling party’s floor leader intended to form a special committee on Jeju 4·3 in the National Assembly, rather than legislating the special act. However, the situation turned around when President Kim Dae-jung issued a special order to prioritize the enactment of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act.

The bill to enact the Jeju 4·3 Special Act was first tabled at the National Assembly on Nov. 18, 1999, and it passed the plenary session on Dec. 16, less than a month later. Conservative groups shouted, “It’s a crap law! It’s unconstitutional!” but it was a belated response.

The best achievement from the enactment is the government’s adoption of “The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report.” It must have been hard to author the report, but winning the government’s approval must have caused difficulties as well. What do you think is the power of the report?

For me, the process of passing the deliberation was several times harder than developing the report. At the time, there were seven deliberation meetings directly headed by Prime Minister Goh Kun. It was like walking on thin ice. The eight concluding pages of the report were read and reviewed by Prime Minister Goh. With the passage of the report, seven draft recommendations for the government were adopted. They detailed the government apology, designation of a national memorial day, use of the case in peace education, creation of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park, and excavation of remains, and most of them have been achieved.

The government’s adoption of “The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report” means that the history of Jeju 4·3 changed in the public domain. In other words, it was revised from the past description as a “communist riot” to the description as a “human rights violation by state power.” A good example is a case in which the Ministry of National Defense used the term “Jeju 4·3 Riot” in “The Korean War History” (2004) but they were severely criticized for doing so and made corrections in 35 descriptions.

The recently published high school Korean history textbooks more broadly cover the report as Jeju 4·3 in the section titled “Efforts to Establish a Unified Government.” The textbook published by Dong-A Publishing also cited my article on the distortion of Jeju 4·3 in the history textbook.

[Yang addresses the United Nations Symposium on Human Rights and Jeju 4·3, held at the United Nations Headquarters in New York on June 20, 2019.]

Since taking office as the 6th President of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation in 2018, you have achieved so many things without a break. You may feel bashful, but could you introduce some memorable events?

I tried to stick to the basics. Part of this is the establishment of a research and investigation team, the publication of the follow-up investigation report, and the significant improvement of the archive search system. As a result, the foundation was assigned to conduct an additional government-level investigation into the case.

We used a two-track strategy to identify the role and responsibility of the U.S. government in Jeju 4·3. We resumed the field survey of U.S. data and published five volumes of the U.S. data collection, and held the UN Symposium on Human Rights and Jeju 4·3 at the U.N. Headquarters in 2019. A Washington Symposium was also planned, but it is regrettable that the conference was postponed due to COVID-19.

Also memorable are the opening of the Jeju 4·3 Trauma Center, the performance of the creative opera “Sun’I Samch’on”, the camellia planting campaign, the supply of 800,000 camellia badges, and the 4·3 training project for 10,000 teachers nationwide over the past 10 years, staged with the Office of Education. I tried to communicate actively with the prosecution, police, and military agencies, going beyond the limits of 4·3-related groups and institutes.

Last year, you took the lead in revising the Jeju 4·3 Special Act, which includes clauses for state compensation for victims and special retrials for prisoners. What is the significance of the revision, and any impressive figures you particularly remember?

It is significant in that the general revision of the act resulted from the efforts to solve the problem of unlawful imprisonments and eventually adopted a national compensation plan. In particular, it is highly appreciated that the statutory state compensation is the first achievement in Korea in terms of civilian casualties that happened before and after the Korean War. It is also significant that a fixed-rate system has been introduced for the compensation and those who have been recognized as victims under the Jeju 4·3 Special Act are subject to compensation.

Until the last minute of revising the bill, the biggest challenge was for adding special clauses on the retrial of wrongfully accused victims and the compensation for the deceased and the injured. The then Justice Minister Choo Mi-ae solved the retrial, while the then Democratic Party leader Lee Nak-yeon opened the door to the agreement by the Ministry of Strategy and Finance, which seemed impregnable. In the process of passing the bill at the National Assembly, none of the opposition party members opposed, which was thanks to Rep. Lee Myung-soo from the People Power Party. The fixed-rate system and the increase in the amount of compensation to 90 million won were supported by Yonsei University professor Park Myung-rim, who advised the research team for the enactment, and Minister of Public Administration and Security Jeon Hae-chul. Rep. We also need to remember Jeju-based National Assembly members, including Oh Young-hoon, the chief author of the proposed bill, as well as the leadership of the Association of the Bereaved Families of Jeju 4·3 Victims, including former chairman Oh Im-jong, who agreed to the proposal from a broader perspective.

Lastly, what is your position on the value and nature of Jeju 4·3?

I would like to emphasize that Jeju 4·3 is a world-historical event, rooted in the division of the Korean Peninsula and the Cold War between East and West. Recently, I summarized and announced the value of Jeju 4·3 in six points: 1) Autonomy and self-orientation, 2) justice, 3) unification, 4) peace and human rights, 5) reconciliation and mutual prosperity, and 6) healing and integration.

For those who ask about the nature of Jeju 4·3, I answer that it was a struggle against unfair oppression and a unification movement that aimed at the unification of South and North Korea. Now that we reached the point of managing the issue of national compensation and retrial, I think it can be a global model for resolving past wrongdoings by the government. I hope we can solve the remaining tasks step by step under this goal.