Communities have always responded to trauma through culture. Whether through subversive theater, dissident poetry or the healing function of traditional shamanic rituals, the fight for justice finds fertile ground in the realm of arts and culture. This stands true for those who were victimized during the Jeju Uprising and Massacre, and this chapter explores the influence of the tragedy in local art, literature, poetry, film and more. Readers are introduced to key figures who have helped direct the cultural response to the massacre as covered by English-language media and chiefly The Jeju Weekly, which has been critical in introducing the world of Jeju culture to an international audience.

The chapter begins with an introduction to the influence of the Jeju Uprising and Massacre on the Jeju artworld by Anne Hilty of The Jeju Weekly. Hilty outlines some of the central figures in “4·3 art” from authors Hyun Ki Young and Han Rimwha to the theater group, Noripae Hallasan. Following this wide-ranging piece, the chapter focuses on specific individuals beginning with an interview with Hyun Ki Young by Darryl Coote. Hyun wrote the groundbreaking 1978 novella, “Sun-i Samch’on,” which led to his persecution by the Park Chung Hee regime. This is followed by a review of another landmark novel on the massacre, “The Curious Tale of Mandogi’s Ghost” by Kim Sokpom. The review is written by historian Robert Neff who highlights the theme of sacrifice that runs through Kim’s work.

Although Hyun’s “Sun-i Samch’on” was the first major literary work to cover the massacre, O Muel’s 2012 film “Jiseul” brought the massacre to the attention of a global audience for the first time. The film was awarded the World Cinema Dramatic Grand Jury Prize at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and his interview with Song Ho Jin of the Hankyoreh is also included. This is complemented by an interview with artist Keum Suk Gendry-Kim who published the graphic novel of “Jiseul” in both Korean and French. She tells Darren Southcott of The Jeju Weekly about her duty as an artist to cover such injustices from

The final two articles cover poetry and art beginning with an interview with local poet Moon Choong-sung whose work “The Whole Island” was read at the 65th Jeju 4·3 Memorial Ceremony in 2013. In an interview with The Jeju Weekly, Moon reflects with melancholy on Jeju’s hardships and the dark cloud of massacre that hangs over him as a poet and as an Islander.

‘Sasam Art’: The artists’ way

Jeju artists lead way to truth, justice and healing

By Anne Hilty

—

Art has a unique ability to move people, to change minds and heal hearts. The use of art to reveal truth, make political statements and initiate revolutions is known throughout the world.

Jeju artists – visual, performance, literary – have been especially influential in the “Sasam” Movement (local term for the mid-20th century period of mass killings), the urge of Jeju people to reveal the truth about the military brutality and deep tragedy of that time.

Art has also helped Jeju people to heal.

In 1979, writer Hyun Ki Young published “Sun-i Samch’on,” a work of fiction depicting events of that era. The first of its kind, this groundbreaking book brought both recognition and persecution to its author. An English translation was published in 2008.

Han Rimwha, a novelist, poet and independent researcher, published a three-volume novel on related themes in 1991 entitled “The Sunset on Mount Halla.” Today the president of the Jeju Writers’ Association, Han describes frequent interrogations as she researched material for her literary work.

• • •

The performing arts have also focused on events of this tragic historical period. A theatre company, Noripae Hallasan, was formed in 1987 as part of the democracy movement and continues to this day. Though investigated, the troupe avoided outright persecution by using symbolism and imagery rather than a more direct portrayal of its themes.

With performances related to the turmoil and massacres of the mid-20th century and other political controversies, this unique group travels from village to village to perform in a traditional style of theatre-in-the-round which includes audience participation.

Yoon Miran, a performance artist who has been involved with the troupe since 1989, identifies the group’s performances as consciousness-raising.

“Art can be used as a sword,” Yoon expressed, “to kill or threaten the enemy – or it can be healing.”

Participatory in nature, the group’s work encourages their audience to express otherwise dangerous or difficult emotions like anger and mourning. The company remains wildly popular to this day and also performs in Japan to the Jeju diaspora.

“Jeju has its own indigenous ways to heal,” said Yoon.

• • •

Kang Yo-bae is perhaps the most well known of ‘Sasam Artists’ and a co-founder of the Tamna Artists Association. While he also creates art seemingly unrelated to this theme, he admits that all of his work is in some way influenced by the events of that terrible time.

He identifies “emotional ups and downs,” citing this artwork work as “mentally difficult” while also acknowledging that doing such work helps to “heal” him. However he admits that he cannot sustain such a focus for long periods of time.

In 1992, Kang’s “Sasam Art” was shown in Jeju, Seoul and Daegu; the exhibition was entitled, “The Camellia Has Fallen.” According to Kim, it was considered a monumentally influential event. When the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park opened on Jeju in 2008, 50 of Kang’s works were displayed in a special exhibition bearing the same title.

• • •

One of the most influential activist-artists today is the aforementioned Koh Gill Chun.

Koh’s work is prolific, and one of his most striking may be that permanently housed in the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park Memorial. Entitled “Death Island,” it is a grouping of 23 alto-relievo sculptures in white plaster and clay, which depict the variety of victims’ tortures and deaths.

Following the discovery of a mass grave on the grounds of Jeju International Airport, Koh created another grouping of sculptures, this one of tragic life-sized figures in clay emerging from earth. It was included in the 2009 Tamna Artists Association exhibit and was entitled, “From the ashes of the earth, we stand.”

Koh describes his “shocking” discovery of US political progressive and scholar Noam Chomsky’s inclusion of this tragedy [“…the suppression of a peasant revolt in…Cheju Island”] in Chomsky’s 1992 book, “What Uncle Sam Really Wants.” He describes this as the initial motivation behind his own “Sasam Art” and political activism.

Koh received a letter of acknowledgment from Chomsky earlier this month.

Numerous writers, artists and performers now focus their creative endeavors on the events of this tragic period with themes of truth, justice and healing. There seems to be a consensus that the truth of the historical events has not been adequately revealed and that while some measure of resolution and recompense has been achieved, neither justice nor healing have been fully realized.

There are many viewpoints in Korea and elsewhere on the events of this period. The details may never be fully known. There is no question that it represents a psychological wounding of the deepest sort in Jeju’s culture.

The artists of Jeju have led the way in understanding and healing from this tragedy.

Kang Yo-bae’s paintings revive

the painful memories of 4.3

A review of a 2018 exhibition of Kang’s work on the Jeju Uprising and Massacre held

at Seoul’s Hakgojae Gallery

By Yi Hwa-soon

—

The work of painter and Jeju native Kang Yo-bae suggests that art and life are inseparable, and that art should breathe the epoch of history.

The work of painter and Jeju native Kang Yo-bae suggests that art and life are inseparable, and that art should breathe the epoch of history.

And there is probably no better illustration of this than his two-part solo exhibition at the Hakgojae Gallery, Seoul, that was on display for the 70th anniversary of Jeju 4·3 that presented some 60 of his historical paintings on the Jeju Uprising and Massacre.

The first part of the exhibition, “Just, Image,” on display from June 22, exhibited Kang’s impressionist paintings; while part two, “Memento, Camellia,” which opened July 15, was itself divided into two sections: “The Camellia Has Fallen” and “After the Camellia Has Fallen,” and dealt with Jeju’s tragic history.

Despite having steeled myself before visiting the gallery, my determination faltered as soon as I saw “One’s Respect for the Photograph of Bert Hardy” (2016). Totaling 455 cm in length (which could cover an entire large wall), the huge painting depicts two scenes: people, heads bowed, tied together like fish drying on a line; and the foaming dark blue sea, their assumed watery graves.

Kang’s inspiration for this painting was a photograph by Bert Hardy, a Korean War correspondent for Picture Post, of Busan prison in September 1950 the moment before a group of prisoners were massacred.

“When I first saw the photograph of the victims in the corner of a newspaper,” Kang said, “I was utterly shocked. I could not separate it from Jeju 4·3. As an artist, I tried to think of how to testify the mass drowning of the innocent people and how to pay due respect to the victims.”

Even before recovering from that shock, I encountered “Infant” (2007), a painting that depicts a mother shot to death on the ground and her baby trying to drink milk from her uncovered breast. Kang painted the image, inspired by a story he had heard from a survivor of the massacre that took place in Bukchon, a northeastern village in Jocheon, Jeju City.

In “Empty Breast” (1992) and “The Remains in the Cave” (1992), Kang has created a diptych where in the former a mother and her baby daughter hide in Billemot Cave to evade Jeju 4·3. But in the latter the viewer is confronted with their corpses as discovered by an academic research team long after their deaths.

Kang also honored the victims through “The Song of the Soil” (1995) by portraying yellow pumpkin flowers blossoming among the people buried in the soil. “A Crow and the Old Tree” (1996) paints wind, an old hackberry tree, a crow and Mt. Hallasan, the things that Kang encountered while wandering through the nature of Jeju for over a decade. In “Song of the Bones” (1998), a skull shouts in the dark, expressing its pent-up anger and sorrow that could not be appeased even by death.

Nevertheless, the exhibition also reveals hope. “Greenness” (2013) is an abstract painting fully painted in red, a color that reminds viewers of the victims and their pain, while showing the green of hope and life blooming from the bottom of the canvas.

“On Jeju, the public suffered from unspeakable pain in silence for too long,” Kang said. “Although the situation has improved, the pain remains deep in their hearts.”

My dinner with Hyun Ki-Young

Jeju writer talks literature, the massacre and his physical and mental torture

By Darryl Coote

—

I first learned of writer Hyun Ki-young a few years back while researching for The Jeju Weekly’s Jeju Massacre series. Hyun, a Jeju native, is credited with having written the first public mention of The Jeju Massacre with the 1978 short story “Sun-i Samch’on.”

I first learned of writer Hyun Ki-young a few years back while researching for The Jeju Weekly’s Jeju Massacre series. Hyun, a Jeju native, is credited with having written the first public mention of The Jeju Massacre with the 1978 short story “Sun-i Samch’on.”

I used the recent publication of an English translation of his story as an excuse to interview the scribe. We met at a small fish restaurant in Shin Jeju for beer.

“Becoming a novelist means to acquire freedom. Literature is freedom,” Hyun said. “But I have a complex in my mind… Why am I so complicated? Because of the 4·3 accident, which I experienced [when I was] six or seven years old. That trauma insists on my mind. I want to be free. In order to be free, I have to write about 4·3 to cure me of trauma.”

Fifty percent of his work, he said, is about the massacre. But even still, it’s not enough to silence his guilt.

“If I die and go to heaven I will meet 4·3 victims. I think they will torture me. Because at my age I neglected them. I didn’t write about them,” Hyun said. “I am afraid of it. I want to write about 4·3 more, more beautifully.”

This is a challenge he claims he has no choice but to accept.

The story that he is best known for is historical fiction, combining the slaughter of 400 people in Bukchon-ri village with Hyun’s experiences during the massacre in the Nohyeong-dong area, his birthplace and the location of the fish restaurant in which we were sitting.

“Because it is history, it wasn’t so difficult to write,” Hyun said.

What was difficult, he said, was describing the behaviours of those who would have been much older than him during the massacre.

In many ways the book contains archetypal characters from the massacre, none more vivid than the narrator’s uncle, a former member of the North West Youth Association (NWYA).

“At that time young women have to get married to NWYA people in order to protect their family,” said Hyun. To this day, former NWYA members live on the island and have families and property acquired through these marriages during the massacre.

This has been one of the more troubling aspects of the massacre; having neighbors who’ve murdered neighbors. Some committed these crimes for their own survival but some, Hyun said, were committed from the evil that occasionally arrests men in positions of uncensored power.

His NWYA character is more the former than the latter, and for a very specific reason: he hoped having done so would have absolved him in front of the Park Chung Hee dictatorship.

This would not be the case.

“I was tortured for three days,” said Hyun.

There were two men from the NIS (Korean CIA), one holding Hyun from behind while the other beat him, threatening him to not write about the massacre again. In the booth of the restaurant Hyun mimed how he was restrained and mimicked taking blows to the ribs.

They made sure not to break his bones, he said.

He wasn’t officially arrested, for if he was there would have to be a trial, which would expose to the rest of Korea the truth of the Jeju Massacre.

“My muscles swelled. The color was ink color, ink color all over my body. Bruise, you know? Ink color, ink.”

The government, almost 30 years after the massacre, was trying to silence any mention of the massacre.

“They didn’t want people to know about 4·3 … 4·3 is trouble and they wanted to keep 4·3 [quiet] forever.”

He is still writing about the Jeju Massacre, and the torture he experienced was reproduced in a book he is currently working on. Though the topic is consumerism, and not the massacre, it is difficult to picture anything he writes to stray far from his “mission,” ordered by those long passed.

“I was tortured because I was writing about this, but if you think of my death I will be tortured by the victims because I didn’t write about it enough.”

‘The Curious Tale of Mandogi’s Ghost’: a review

Kim Sok-pom’s fiction shines a light on Jeju’s troubled past

By Robert Neff

—

Ghosts are often said to haunt places where great suffering and loss of life has occurred. Thus it is no wonder that Jeju is rumored to be haunted.

The April 3, 1948 uprising on Jeju and its subsequent brutal suppression by the South Korean government is still a sensitive issue amongst Koreans – especially those on Jeju. This short story, although done in a light folktale style, explores some of the darkness of the turbulent era of the 1930s and ’40s.

The protagonist is Mandogi, a young priest, who as a boy was abandoned by his mother at a temple on Jeju Island in the late 1920s or early 1930s. It is through Mandogi’s innocent eyes that we witness society’s horrors and the sacrifices that desperate people are forced to make. We follow Mandogi’s life from the morning he is abandoned at the temple, to his days spent working in the mines of Japan, to his return to Jeju and role as an reluctant participant of the Four Three Incident, a role which causes his execution and subsequent return as a ghost.

The author, Kim Sok-pom, was born in Japan in 1925 to parents who had recently emigrated from Jeju Island. He spent much of his early childhood on the island. According to Cindi Textor, the translator, Kim has not been able to return to Korea after World War II but identifies Jeju as his “ancestral homeland.”

As Textor notes, despite Kim’s claim that Jeju is his “ancestral homeland,” he is “perhaps ideologically aligned more closely with the North.” This becomes quite apparent upon reading this book.

Although he portrays the islanders as hapless victims of the political struggle between communism and democracy, he also highlights their selfishness and willingness to sacrifice others. When a policeman takes an interest in a young married woman whose husband is away, the father-in-law willingly sacrifices her virtue for the good of the family.

He explains it away with: “Since ancient times, in our Korea, which values virtue above all else, it must be said that the commands of your husband’s parents, especially his father, are higher than those of your husband. And filial piety is the highest virtue.”

The girl, unwilling to dishonor her husband, hangs herself from the family’s persimmon tree. Instead of earning respect, her ghost is scorned for endangering the entire village and not proving her filial piety.

The policemen, all members or friends of the Northwest Youth Association — an anti-terrorism organization established by President Rhee Syngman — are portrayed as ignorant tyrants who abuse the islanders for their own gain. This is emphasized by the police captain’s inability to write and the station chief’s boast: “In our Republic of Korea, as long as you don’t agree with commie ideas, you’re allowed to rape, steal, and murder.”

To these simple police, a mere display of the color red casts suspicion on one’s political views. Even hanging cayenne peppers from the roofs so that they could ripen in the sun to a bright red is taboo.

Even the sanctity of the temple is not spared from the author’s cynicisms. Mandogi’s illegitimate birth is the result of a brief encounter in a Korean temple in Osaka, and one Jeju priest abandons the Jeju temple to visit his many mistresses. However, it is the temple manager, Mother Seoul, whom the author develops into a symbol of the decadence of the South Korean capital.

Described as a “hysterical old widow,” she had operated an inn in a red light district of Seoul before coming to Jeju Island, where she is regarded with some respect, if not fear. Her relationship with Mandogi is complicated. Despite the sadistic beatings she administers to him on a regular basis, he regards her, perhaps somewhat pathetically, as a surrogate mother. At times she shows a rough compassion but is not above using him, even sexually, or sacrificing him for her own well-being.

Sacrifice seems to be the theme of this book, and on more than one occasion I felt as if I were sacrificing my time in reading it. It is not an easy read. It won’t do for purely selfish entertainment, but that being said, it is a book that I would recommend to anyone with an interest in Korean history or society during the years just before the Korean War. I especially enjoyed the ending, but I won’t elaborate because I don’t want to spoil it for you, the readers.

Jeju 4·3 film wins prestigious prize

at Sundance Film Festival

‘Jiseul’ by director O Muel is the first Korean film to win the award

By Song Ho-jin

—

“What led me to make this film were the souls of the Jeju islanders who were massacred,” the director said, “and I also think that their souls helped us during the filming. I’d like to share the award with them.”

“What led me to make this film were the souls of the Jeju islanders who were massacred,” the director said, “and I also think that their souls helped us during the filming. I’d like to share the award with them.”

O Muel, the 42-year-old director of “Jiseul,” responded to news of the film’s Grand Jury Prize not with pride in his accomplishment, but with respect for the victims of the Jeju 4·3 Massacre. “I think maybe the sorrow of those souls reached the heavens,” he declared as tribute to them.

Beginning on April 3, 1948, between 14,000 and 60,000 people¹ on Jeju Island were killed in an uprising that ensued after the South Korean military fired on a demonstration commemorating the end of Japan‘s colonial occupation of Korea. The South Korean army’s and rightist group’s brutal suppression of this uprising caused the destruction of many villages on the island, and sparked demonstrations on the Korean mainland.

The suppression lasted until May 1949, while isolated fighting continued into 1953. Many residents of Jeju escaped from the massacre to Japan.

The film, which dramatizes the events of the massacre, earned top honors in the world cinema category at the 29th Sundance Film Festival, the most prestigious independent film festival in the world. The organizers announced the jury’s unanimous decision at a Jan. 26 award ceremony in Park City, Utah.

Sundance awards Jury Prizes for the best entries in US and world documentary and film, for a total of four categories. This marks the first time a South Korean film has won one of these top prizes at Sundance. In 2004, Kim Dong-won’ s documentary “Repatriation” received a special Freedom of Expression Award at the festival.

Speaking to the Hankyoreh by telephone on Jan. 26, O said he was contacted by the festival organizers about the result the previous day while changing planes in Tokyo on his way home.

The award for “Jiseul” adds to the list of honors received by South Korean films at major festivals over the past couple of years. In 2011, Yi Seung-jun’s “Planet of Snail” won in the feature category at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, one of the world’s top documentary festivals. Last year, Kim Ki-duk’s “Pieta” won the Golden Lion at the Venice International Film Festival, one of the world’s top three film festivals.

Film industry insiders said the awards are an especially major coup for documentary and art features that have failed to find their way to screens back home.

Set during the events of the Jeju Uprising and Massacre in winter 1948, “Jiseul” is based on the true story of Jeju Islanders who hid in the caves of Seogwipo after an order from the US military designating all residents within 5 k.m. of the coast as “rioters” and ordering their execution. Shot in black and white for 250 million won (about US$231,500), it adopts the format of an ancestral rite as it pays respects to the tens of thousands of people who lost their lives at the time.

In scene after heartbreaking scene, it uses intensely powerful images to capture the islanders, whose amusingly fumbling response to their dire situation only underscores the tragedy of what follows. The title is a word in the local dialect for “potato,” which symbolizes the hope of survival in the film.

O, himself from Jeju Island, commented on the significance of the film’s reception.

“4·3 needs to be viewed in terms of world history as a Cold War-era massacre of civilians in which the US military administration was complicit,” he said. “It is significant that a story like this was screened in the US and acknowledged by artists there.”

The director recalled a tearful US audience member at the festival, apparently in her 50s, who thanked him for making the film.

“Different countries have different languages and ways of making films, but I think all of us share the same pain that comes through when innocent people are dying,” he said.

Originally published in the Hankyoreh on Jan. 28, 2013.

1 Although there are over 14,200 official victims, the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation estimates that up to 30,000 could have lost their lives in Jeju 4·3. Nevertheless, the death toll has been estimated as high as 60,000 by some historians.

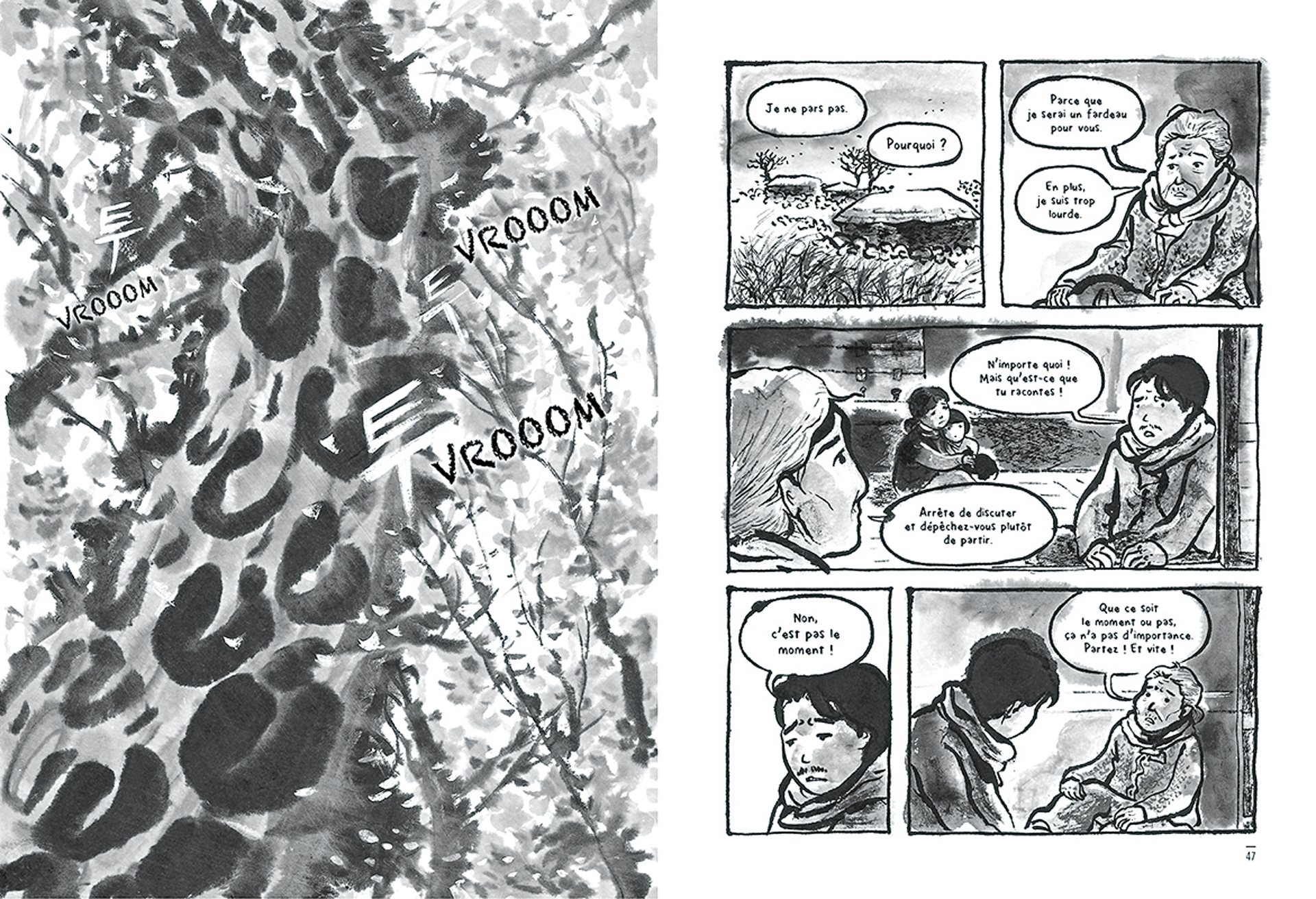

Artist’s ‘duty’ to make ‘Jiseul’ graphic novel

Gendry-Kim recreates award-winning 4·3 movie

in French and Korean manhwa

By Darren Southcott

—

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim had been told it was a film she must see, and all it took was a look at the poster to convince her to take on the job.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim had been told it was a film she must see, and all it took was a look at the poster to convince her to take on the job.

“The woman wears traditional clothing, holding a bag. The young soldier looks directly at her but cannot pull the trigger, feeling she is a younger sister or relative. Within the image you have the whole of Korea’s contemporary history.”

The unmistakable scene of a rifle-toting soldier aiming at the head of a young woman, framed by Jeju’s oreum, is taken from O Muel’s “Jiseul,” winner of the prestigious World Cinema Dramatic Grand Jury Prize at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival.

Gendry-Kim’s task was to recreate the film in French and Korean for a graphic novel, or “manhwa.”

“Even before seeing ‘Jiseul,’ I knew I wanted to do it. Then when I saw the film, the cinematography itself was already like a work of art,” the native of Jeolla said.

She was moved by “Jiseul”’s touching representation of the Jeju Massacre (Jeju 4·3) which left up to 30,000 dead between 1947 and 1954.

Despite director O having studied traditional Korean art himself, he did not work alongside Gendry-Kim in making the book, although she was influenced by his work’s essence.

“Normally, movies or graphic novels portray massacres brutally, but ‘Jiseul’ is warm and beautiful. Rather than showing massacre, it even brings a smile to our faces by showing the innocence of farmers who only care about their potato crops or children,” she said.

Her traditional ink drawings are also powerful for their bleak beauty, sometimes without dialogue for page after page. Gendry-Kim had to make some changes, however, such as when choosing standard Korean over Jeju dialect.

“At first I tried to use only some words such as ‘oemeong’ [mother] and ‘abang’ [father] or some verb endings, but the ‘Jiseul’ people suggested using either the original Jejueo, or choosing standard Korean. I decided to go with the latter as it is important for people to understand,” she said.

Tackling tough subject matter

Gendry-Kim majored in Western painting and studied sculpture at L’École Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs de Strasbourg, but after exhibiting her work across Europe she eventually moved into graphic novel drawing.

It was not long before she was disillusioned with the formulaic manhwa storylines sent to her, which were dismissed in France as Japanese mimicry and lowbrow. She thus began to draw and write her own, following the “artist’s duty” to speak up on historical and social issues.

Her work has since covered dictatorship in 20th-century Korea, Japanese sexual enslavement of Korean “comfort women,” and she is currently working on a book on Jeju’s haenyeo, or women divers.

“I have always had something to say, and it is not the image but the message that is important,” she said.

She hopes this current work can help bring some solace to Jeju’s massacre victims and — also being published in French — bring more international awareness to the tragedy.

“What was most moving was that [the people] had to hide the truth for so long as if they were criminals … Even though it is only a little, I want to let the long-suffering families know that they are not alone and have not been forgotten,” she said.

Originally published in The Jeju Weekly, April 20, 2015.

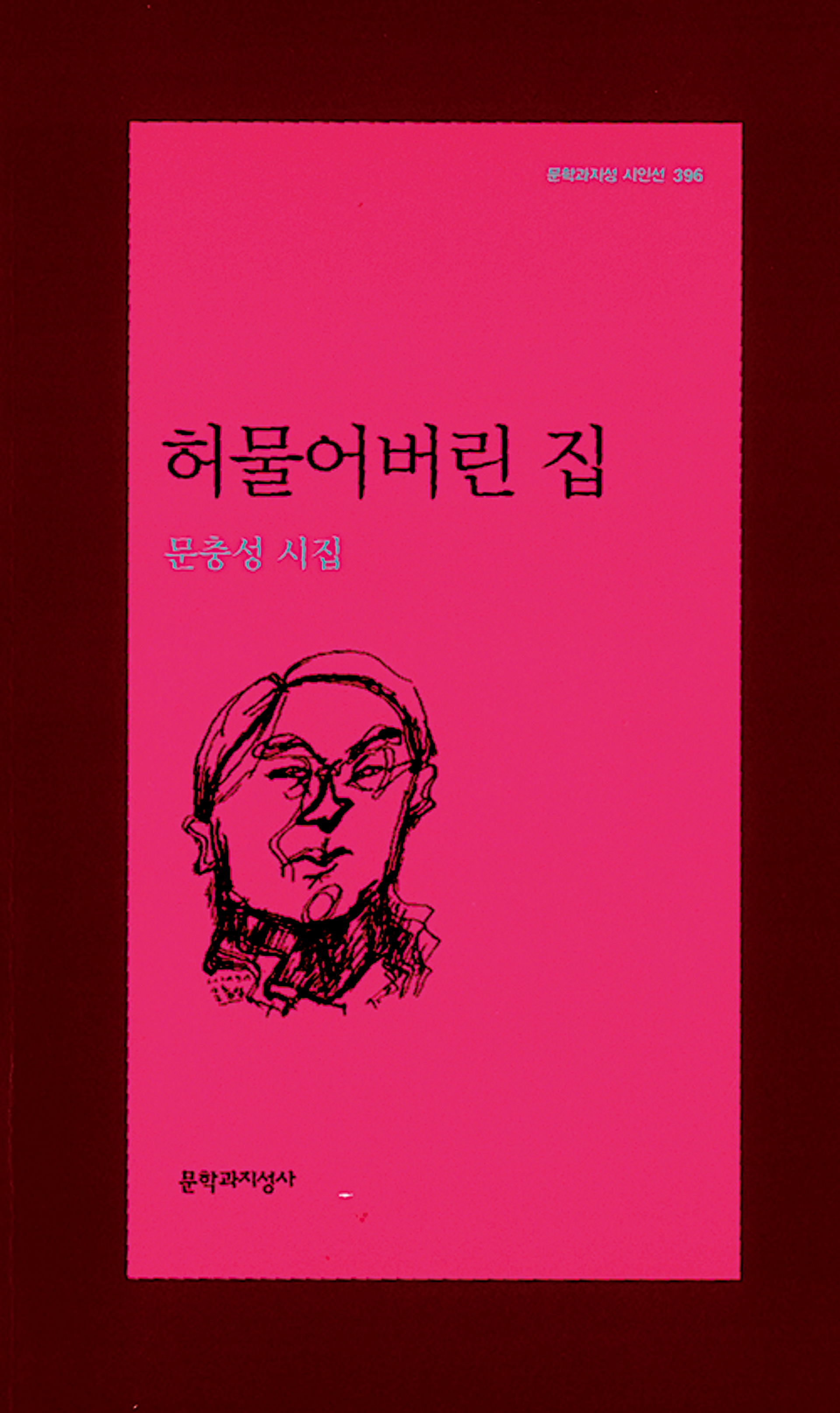

One man’s search for poetic justice

Moon talks about the lingering scars of Jeju 4·3

and his mission to heal the wounds through poetry

By Darren Southcott

—

It was at the 4·3 Massacre 65th Memorial Ceremony that I first heard the work of Jeju poet Moon Choongsung. At the end of the ceremony, before wreaths were laid, his poem “The Whole Island” was read. The last verse ran:

It was at the 4·3 Massacre 65th Memorial Ceremony that I first heard the work of Jeju poet Moon Choongsung. At the end of the ceremony, before wreaths were laid, his poem “The Whole Island” was read. The last verse ran:

“What is it?

Where was the freedom?

The whole island was death.

The whole island.”

The poem provided a moment of introspection, the reflection that Moon regards as essential for reconciliation as Jeju’s history disappears. “I dream of that final voyage, setting out for the unknown of that nostalgia, the nostalgia of that unknown,” he pens with melancholy in his anthology, “Heomuleobeolin Jip.”

Now 74 years old, Moon was a journalist for 15 years at Jeju Ilbo and spent 20 years as a professor at Jeju National University. His voyage began back in middle school, however, as he was visited by tragedy like so many Jeju residents of the time.

“I was in the fourth grade of middle school when 4·3 happened and then the Korean War followed that — my whole childhood was war,” he said.

• • •

While for some the conflict is long over, for Moon and other survivors the communal and familial divisions linger to this day. Ceremonial acts of reconciliation are no substitute for the real thing, he pointedly writes in “4·3 Song:”

“Even yet it’s not over.

It will never be over.

Just once a year you go, up that hill.

All you people who gather, you just sing of forgiveness, reconciliation, togetherness and peace.

Your tears have just turned from red to white.”

The red of pain, hatred and hurt, has become empty and shallow — not a whiteness of purity, but of vacancy.

Moon included “4·3 Song” in his anthology to complement “The Whole Island,” both of which cover Jeju 4·3: “The first deals with the legacy of 4·3 in the present and the latter reflects on the past. I wanted to do this because we are still living 4·3 now — it is not finished,” said Moon.

Moon wrote “4·3 Song” as a sonnet with the first two stanzas of four lines followed by two stanzas of three, representing 4·3 in its very structure. In desperation he writes, “What are you doing? Stop fighting like enemies,” a lament that was sadly prescient.

“It is even evident in the reaction to ‘The Whole Island’ that was read at the 4·3 ceremony. I use the term ‘san-pok-do-deul’ (mountain rebels), a term that was naturally used at the time, but people were angered by it, saying it was offensive. I was writing poetry, not making a political statement.”

• • •

Returning again to Jeju’s dark past, Moon sees Jeju’s victimhood as a recurrent theme in the face of hegemonic forces from near and far. “When I was young, Jeju was known as ‘the island of tears and sighs’ due to its history of invasion and conquest, from an independent Tamna, to Mongol colonization, to its use as an exile island in the Joseon era, to Japanese occupation and then 4·3,” he said.

Moon is cheerful and softly spoken, whose quietness belies his reflective nature which is amply indulged by the island’s predicament. The glossy images of a holiday-maker’s paradise provoke a wry smile from the artist.

“It is interesting for me that people come here and see Seongsan Ilchulbong or haenyeo and see beauty and something wonderful. Actually these things represent the hardship and pain of Jeju,” he said. “When I see haenyeo I see the fight for life and when I hear their songs I recall not romance but hardship,” he said.

For Moon, the beauty of the landscape, now famed globally, is something that hides this tragic story of Jeju’s past.

“Jeju has another name that has come down to us: the island of divine punishment.”