After the international reporting on the massacre at its height in 1948 and 1949, coverage of Korea in the years that followed was dominated by the Korean War (1950-53). Even after hostilities ceased between North Korea and South Korea, domestic reporting on the massacre was suppressed by authoritarian governments particularly under Park Chung-hee (1961-79) and Chun Doo-hwan (1980-88). During these decades the victims of the massacre were tainted as “reds” and victims’ families were discriminated against and silenced. In such a climate, and given the involvement of the U.S. military government, it is unsurprising that there were few English reports on the massacre. When Jeju was covered by the international press between the 1970s and 1990s, the coverage was highly orientalistic with idealised representations of sandy beaches, exotic Asian culture and

“haenyeo” diving women portrayed as mermaids.

Notwithstanding the scholarly work by John Merrill and Bruce Cumings previously introduced, it was not until the turn of the 21st century that the Jeju 4.3 Uprising and Massacre was explored in the international press. Although the work has been varied, and at times extensive, the coverage previewed here is limited to four pieces that stand out for their importance and scope. The first is an Associated Press account from 2001, which first reported the ongoing truth and reconciliation commission to the world. This is followed by a piece from the same year by Howard W. French of The New York Times, which covers the truth-finding efforts of victims of the massacre. The third piece, originally published in 2008, is written by Hamish McDonald of the Sydney Morning Herald and he frames the massacre within the context of the movement for transitional justice in South Korea post-democratization. Finally, the work of Andrew Salmon in the Asia Times reflects on what has been achieved and what remains to be settled on the 70th anniversary of the massacre in 2018.

South Korea Reviews 1948 Killings

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — The government is reviewing the cases of 14,000 people who were reportedly killed during a crackdown on a leftist uprising by the U.S.-backed government in 1948 following South Korea’s liberation from Japanese rule.

A government panel will verify victims and offer medical and other benefits to survivors and families of the slain.

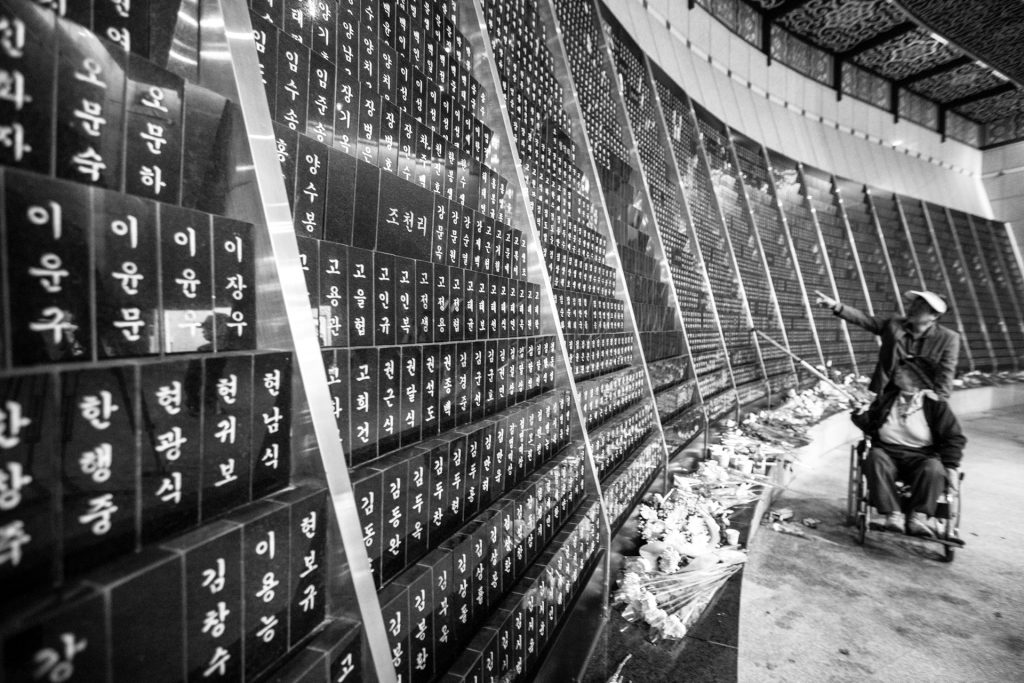

On Tuesday, the committee completed the first years of its investigation and plans to wrap up the probe by February 2003 and build a large memorial for the victims.

Fighting between leftist guerillas and government forces in the southern island of Jeju followed the end of World War II.

Estimates of those killed or injured in the government crackdown range from several thousand to 50,000.

Many victims are believed to have been residents executed by government forces who suspected them of being leftist sympathizers. Then-President Syngman Rhee saw communism as the biggest threat to his government.

Last year, the government of President Kim Dae-jung, a former pro-democracy fighter, won parliamentary approval of a special law that mandated an official investigation.

The first police crackdown in Jeju began in March 1947, when police opened fire on demonstrating residents.

The unrest escalated as police and soldiers hunted down leftists, and guerillas operating in the island’s rugged hills attacked police and government buildings.

President Rhee, who took power in August 1948, declared martial law on the island.

Survivors argue that Washington is partly responsible for the Jeju crackdown because the U.S. military supervised the southern part of the Korean peninsula until Rhee’s election, and supported his rule thereafter.

Jeju is now a popular destination for Korean honeymooners and other tourists.

Originally published in The New York Times, Oct 24, 2001.

South Koreans Seek Truth About ’48 Massacre

By Howard W. French

—

A half-century later, Kim Hyoung Choe has no trouble finding his way back to the spot where he hid in the brush on this fragrant, nutmeg-forested mountain and watched helplessly while soldiers mowed down much of his family.

Mr. Kim had been urged to hide in a cave with other relatives as the attackers closed in, but his instincts told him it was not safe, and he managed to conceal himself in the brush and then crawl away. When he returned to the scene a day later, he said, he saw the bodies of at least 100 villagers, their hands tied behind their backs, being doused with gasoline by government forces.

A series of massacres on Mount Halla, which rises over Jeju Island, between October 1948 and February of the next year are estimated to have killed 30,000 people, and rank among the worst atrocities this country has ever seen.

Yet many Koreans, especially those who have never lived on Jeju Island, in the far south of the country, know little or nothing about it.

Japan’s history of violence toward Korea and other neighbors still brings angry protests in South Korea, as was the case during the recent visit by Japan’s prime minister, Junichiro Koizumi. But many Koreans say the time is past due for them to begin clearing the historic skeletons out of their own closets.

The Jeju massacres were part of a particularly brutal effort by the government in the southern part of Korea to root out those it suspected of being Communists on the eve of the country’s civil war.

The story of what happened in Jeju is an all too familiar cold war tale of excessive ideological zeal. With the split between North and South Korea taking root, elections were organized in the southern part of the country, where there was a strong American military presence, in May 1948.

The elections were meant to highlight the growing contrasts between the two halves of the country, but in Jeju, where resentment of heavy-handed administration by people sent from the mainland ran deep, the elections were boycotted in two districts, the only ones in the southern part of the country to abstain.

American commanders in Korea were furious, and after a series of incidents their South Korean counterparts embarked on a campaign to cleanse the island of supposed Communist agitators.

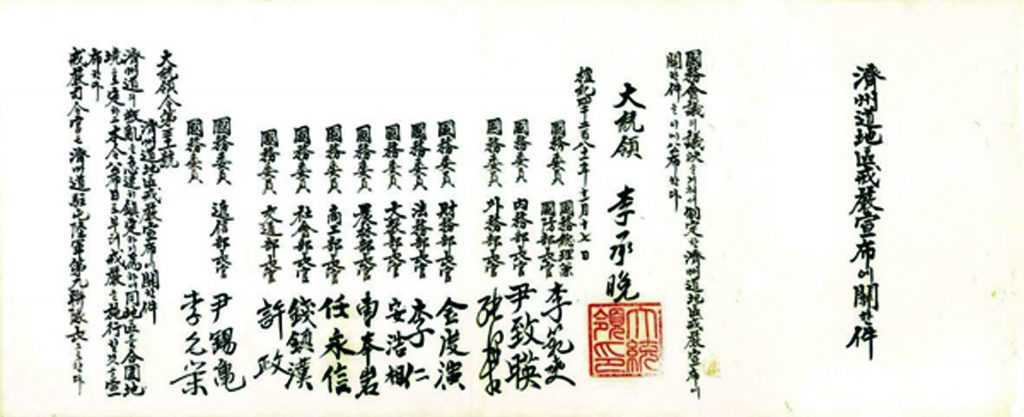

Although he concedes that no documentary evidence exists that the Americans knew what happened, Yang Jo Hoon¹, a prime ministerial appointee who heads a committee established to collect testimony about the killings, believes with many others here that the Americans must have known of, and perhaps even ordered, the crackdown. A team of South Korean researchers is in the United States now seeking proof of an American role.

History textbooks here still give the Jeju massacres only cursory mention. ”I feel very frustrated and angry even now,” said the 80-year-old Mr. Kim, his face heavily creased from years of outdoor work as a beekeeper.

”Those who were killed were never even officially identified. Even now their children and grandchildren come to me to ask what kind of people their relatives were. It makes me feel horrible to realize that people could have disappeared like this without leaving even a trace of themselves.”

In places like Jeju the debate about how textbooks present history has entered a second phase.

In addition to demanding an accounting of atrocities by foreign invaders like imperial Japan, in one country after another local community advocates, historians and human rights groups are pressing governments to acknowledge massacres and other large-scale rights abuses committed against their own people.

On the Japanese island of Okinawa, demands have grown for official recognition of the killing of large numbers of local residents by Japanese troops to prevent them from surrendering to American forces in 1945. In Taiwan, civic groups have mounted increasing pressure for an official accounting of the deaths of between 15,000 and 30,000 people by Chinese Nationalist forces in 1947.

A monument to the victims in Taiwan was erected in 1995, but people pressing the issue say that even now the facts have not been fully investigated.

In South Korea, until a decade ago, the Jeju massacres were ascribed both officially and in textbooks to North Korean infiltrators. Gradually local journalists, university students and members of Parliament began pushing for recognition of what historians say really happened: a largely unfounded witch hunt that resulted in the killing of more than 10 percent of the island’s population.

”The National Assembly passed a law about the massacres for the first time in December 1999, and the government began to investigate this incident for the first time only the following September,” Mr. Yang said.

”All along,” he said, ”the government has known that thousands of innocent people were killed, and that’s why they made a lot of noise about a Communist threat. People were threatened with jail for so much as mentioning the matter. Relatives of the dead were afraid of being labeled Communists too.

”Even today, many people are still too afraid to come forward and tell us what they know.”

Still, even without such testimony, much is already known. Working together, police and army units declared any part of the island more than three miles from the coastline — the forested interior areas that were presumed to be the lair of rebels — to be enemy territory and unleashed a merciless campaign of terror, including the burning of scores of villages, summary executions and widespread torture.

”I still don’t know how I survived,” said Mr. Kim, the beekeeper. ”When I returned here to look for my relatives, they were carting off the surviving women and children. There was still plenty of shooting, and they were setting fires at all of the cave entrances they could find to suffocate the people inside.”

Mr. Yang, a Jeju native, says that when he was an agitated teenager, his parents often told him cryptically that ”you are very lucky to be growing up now instead of in our era.”

Later, as a university student, he read a novel that spoke of the Jeju events and finally understood clearly for the first time what his parents had meant.

He became a journalist, then a prefectural government official in Jeju and spent five years researching the massacres. Local residents say he is as responsible as anyone else for causing the details of the Jeju tragedy to come out into the open.

These days, Mr. Yang, 41, says he has one wish. ”The facts of Jeju are still not taught in schools, even today,” he said. ”My goal is to make the whole nation recognize this history.”

Originally published in The New York Times, Oct 24, 2001.

1 Yang Jo Hoon wrote the foreword for this volume and is currently chairman of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation.

South Korea owns up to brutal past

By Hamish McDonald

—

Something remarkable has been happening in South Korea this year, without getting much attention anywhere.

It has been a nation dragging its darkest secrets into the daylight – not historical crimes committed by the long-dead, but those carried out during the 60-year life of the Republic of Korea.

The stream of reports coming out of Seoul’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission are unsettling not just for Koreans, but also allied countries, including Australia which defended the southern Korean state and supported its successive leaders.

Out of the competing barrages of propaganda that have shrouded the 1950-53 Korean War, we are finally getting conclusive admissions that some of the worst atrocities, blamed at the time on the enemy, were in fact committed by our side – and we knew it.

The commission is the legacy of Roh Moo-hyun, the former human rights lawyer and political liberal who was South Korea’s president for five years until February. It was set up in December 2005, and operates with a staff of 240 and a budget of $US 19 million (AUD$ 29.7 million) a year, with the daunting task of opening up a century of hidden history.

• • •

One of the worst incidents preceded the Korean War, in 1948, when the new Syngman Rhee government installed in Seoul by the United States ordered its army to suppress a leftist revolt on Cheju Island. About 30,000 local people were gunned down.

• • •

At a recent ceremony in which the Supreme Court Chief Justice, Lee Yong-hoon, bowed his head and apologised for unjust court judgments in the past, Lee said the courts had to “guard against judicial populism”.

Of course the findings reflect badly on the right, but even worse things will be unearthed if a similar inquest is ever held into North Korea’s history.

The exercise suggests an impressive maturity and sophistication in South Korea, a lesson for its bigger neighbours Japan and China.

Originally published as an editorial in The Sydney Morning Herald, Nov. 15, 2008.

On Jeju, Korea’s island of ghosts, the dead finally find a voice

70 years ago, an estimated 30,000 people were massacred in an anti-communist blitz on today’s vacation island of Jeju. Now, fingers point at America

By Andrew Salmon

—

• • •

“Not many people know what happened on this island 70 years ago,” said Yang Yoon-kyung, chairman of the 60,000-member Association of Bereaved Families. “This pains us.”

Across Jeju, there is an almost desperate urge to inform the world. Last month, a restaurateur refused payment for drinks, imploring a visiting reporter to write the story.

“Please let people know,” pleaded Kim.

Still, there are contradictory narratives about “4·3.”

While some partisans certainly had North Korean connections, Jeju tour guides label them pan-Korean nationalists. Go¹, the massacre survivor, is even-handed. “During the day, the soldiers and police bullied us,” she said. “At night, the armed resistance came down and bullied us.”

The numbers killed are questioned by some. Millett, in his history, cites census figures between 1946 (233,445) and 1949 (253,164) which actually show a rise in the island’s population. But even Millett concedes that the peace won was “Carthaginian” – a reference to the city famously annihilated by Rome.

There are no surviving partisans: Only a handful escaped to Japan. The victors – those who did the killing – never confessed and were never punished for their excesses. “Not a single person has spoken up from the police or paramilitaries,” Kim said. “Maybe they are ashamed.”

Still, there have been reconciliatory moves between representatives of victims and the security forces. “Every year, we meet and we pay respects at different memorial parks; we go together,” said Han Ha-young, chairman of the Jeju City branch of the Bereaved Families Association. “The police officers were also victims.”

Younger people dispute this. “Deep inside their hearts, they still hate each other,” said Kim. “We are very uncomfortable with the word ‘reconciliation,’” a tour guide admitted.

• • •

Originally published in Asia Times, April 3, 2018.

1 Go Wan-soon, a resident of Bukchon-ri, was nine years old at the time of the Bukchon-ri Massacre