‘Flowers Bearing the Memory of that Day’ The Eve of the 73rd Anniversary Memorial Ceremony of Jeju 4·3 There remain still many names to remember

‘Flowers Bearing the Memory of that Day’

The Eve of the 73rd Anniversary Memorial Ceremony of Jeju 4·3

There remain still many names to remember

Written by literary critic Kim Dong-hyeon

Photo by Kim Gi-sam

What concerned me most during the preparation of our performance “Flowers Bearing the Memory of that Day” to be held on April 2, 2021, the eve of the 73rd Anniversary Memorial Ceremony of Jeju 4·3, was how to pass down memories. What, and how, to remember was what mattered in planning the event. The performance aimed to suggest an assignment to our younger generations that they must remember Jeju 4·3.

A bill to revise the Jeju 4·3 Special Act was passed in February: the first complete revision to the law in 21 years. The revision newly regulates “consolation money” instead of compensation and indemnification to the victims and special retrials for those who were convicted by military courts in 1948-49. Nevertheless, there remain many names that have yet to be remembered. And still after the decision of the Constitutional Court in 2001 to dismiss a request for adjudication on the constitutionality of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act, there are still “forgotten names” as evidence that remembering Jeju 4·3 is yet complete.

The performance, hosted by the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, was a simple attempt to artistically describe issues that followed the enactment of the special law. The Jeju People’s Artist Federation, the organizer of the event, has constantly advocated for the theme of memory. This is why the event focused on the shooting incident of March 1, 1947, the general strike on March 10 of that same year, and the uprising on April 3, 1948. Furthermore, the performance aimed to look back on our attitudes toward Jeju 4·3 after the enactment of the special law in 2000.

After the enactment of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act, the meaning of Jeju 4·3 was weighted more on “the victimization of the innocent,” rather than on its historical significance of resistance. The rhetoric of “those who were killed meaninglessly” was one of the centerpieces of the performance regarding the tragedy of Jeju 4·3. But come to think of it, they were not killed without reason, just like in the poem “Tomorrow” by Kim Gyeong-hoon, they became meaningless only because they were killed. That is what Jeju 4·3 is really about. After 73 years still many names remain locked, and this is what we tried to shed light on in our performance.

Now, being aware of this, the difficulties we had in preparing the performance was how to develop an effective, artistic plot. The stage is not a place for rambling but a sphere for commemoration and harmony where all the people of Jeju, including the families of the bereaved, can reminisce. This is why we wrote “Flowers Bearing the Memory of that Day” as the subtitle of the performance, which had two goals: “to mention the tragedy without being grief-stricken” and “to break through taboo to sympathy.”

Unlike previous years, we plotted a story. As the curtain opened and lights turned on, a storyteller described that there are still many who we should remember despite what we have achieved in the revision of the special law. Then, a monologue of a grandmother began. “Father, it is a good day today. A truly good day in my life that I did not expect to come. Still, father, all that is left with me are tears. You were always in hiding, whether you were alive, or dead…” The monologue of the old woman suggests the necessity to bring up the issue again as there are still those who were not recognized as victims even after the Constitutional Court’s decision in 2001. In the next scene, the grandmother visited her Teuri uncle, a herder, who was also a device to inform the audience of a need to remember the forsaken.

Since the event was a story-based performance, the actors on stage drove the plot. However, with the intention of keeping the atmosphere light, choruses were inserted. The first song was “Do You Hear the People Sing?” from the musical “Les Miserable.” The lyrics were partially revised to show that the people at the time yearned for a united Korea following liberation. “Let’s sing a song, a song of passion and of the people. /We cannot live in this divided land, as we shout. /Holding our hands together, let us march, and into one. /When April comes, we all march on a single path.” Songs that were actually sung during Jeju 4·3 were considered for staging, however, the decision was made to go with more publicly well-known songs.

What I was deeply worried about while preparing this performance was the transmission of memories. In the face of time, the problem of memory becomes greatly important. The performance aimed to suggest an assignment to society that our young generations are to remember Jeju 4·3. This is why, after the chorus, two young students, a boy and a girl, discussed tasks regarding Jeju 4·3. The scene was also set in 2000 when the two students were depicted as college students as the special law was enacted. It is a message to those who were born in 2000 that they are the ones who should remember Jeju 4·3.

Another attempt to reinforce this message was the inclusion in the performance of Lt. Moon Sang-gil who assassinated Col. Park Jin-gyeong on June 18, 1948. While Col. Park’s memorial stone still lies in the Loyal Dead Cemetery of Jeju, still few people remember Lt. Moon, who would later be executed, at the young age of 22, for murdering Col. Park. Some might say Moon’s terrorism was “adventuristic.” (A former senior public official who saw the play actually posted a message to his Facebook page following the performance questioning the glorification of terrorism.) However, the assassination was not a direct cause of the massacres of Jeju 4·3. As soon as his term as the commander of the 9th Regiment of National Constabulary began, Park gave orders to indiscriminately apprehend the people of Jeju, and the casualties that followed were serious. Moon’s deed was the culmination of his fundamental question as to what a soldier must do to protect the life and well-being of the people. Moon’s last statement shows this well. “I part for the afterlife, leaving my 22 years in this world behind. You are soldiers of Korea, and the last thing I want is for you to become soldiers killing your own people under the command of the United States. Please, do not forget my last wish, as I say goodbye to you.” The will of Lt. Moon was introduced during the performance. It was our intention to remember his name.

The performance has actively bolstered arts regarding Jeju 4·3. Also this year, artistic trials aimed at describing Jeju 4·3 were introduced on the stage. The role of Kim Si-jong, a stowaway poet who sneaked into Japan during Jeju 4·3, was performed by Kim Gyeong-hoon, an old friend of Kim Si-jong, who is also a poet. In a book titled “Spring goes, yet another spring comes” published by the Association of Writers for National Literature, Jeju Branch, Kim Gyeong-hoon interviewed Kim Si-jong. One of the lines from the interviewee’s work, “Live in Joseon and in Japan,” as well as his poem, “Tomorrow,” were recited on the stage. Also, lines from the novels “Thirsty gods” and “A spoon on earth” by novelist Hyeon Gi-young were recited by members of the association. What made the event more meaningful was the performance by Wan Yiwha, a Myanmar citizen in South Korea. Wan’s father was a singer of Myanmar’s Karen ethnic minority group. The recent demand of the people of Myanmar for democracy, and the violent oppression by the military junta there, resembles what happened during Jeju 4·3. Wan’s performance served as a chance for the people of Jeju, who suffered Jeju 4·3, to support the people of Myanmar.

The event paid particular attention to the missing people. At the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park, there are 3,900 stones in memory of those who went missing during the seven-year tragedy. We must not forget them. They prove that Jeju 4·3 is still ongoing. When we visited the park to write down names to call out on stage during our performance, we were taken aback by their young ages. There was a young individual who died at the age of 20. A child, who had lived not even a full year, screamed, and a father lamented over losing his two dearest children. Another one born April 25, 1916, in Sangye village, Jungmun district, went missing in 1950 after the preliminary inspection. Yet, another one born Feb. 11, 1924, in Sindo Village, Daejeong District, was reported missing from what is now Jeju International Airport early in October 1949. Each of the three short lines that describe where and when they were born and went missing were read out on the stage so that they would not be forgotten. With the grave for the missing people as the background, their names and records were called. We wanted to call all 3,900 names if time allowed. Only 11 names were called at the event. As we called their names, a picture of red camellia flowers was projected onto a screen. They became “the flowers bearing the memory of that day.”

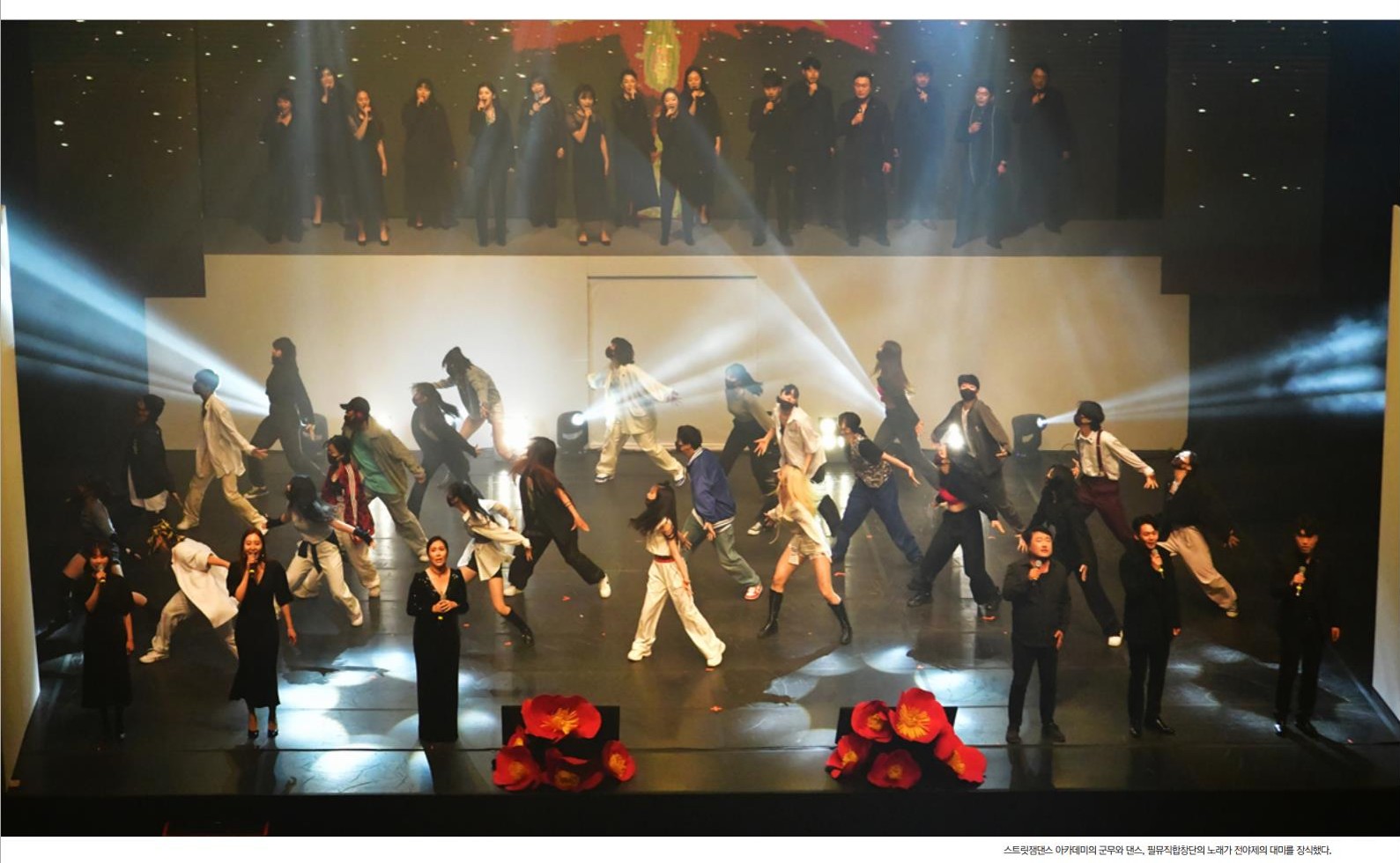

The finale scene consisted of the grand chorus and group dance performance presenting the song “This is Me,” from the movie “The Greatest Showman,” edited for the event. It showed our resolution, to remember the grief and for it not to be buried within and to speak about what is to become of tomorrow. When we heard the applause after the curtain closed, we still felt something was missing. It was because there were those who could not attend the performance due to COVID-19 protocols. We give our special thanks to the People Who Remember Jeju 4·3 organization and Mr. Cho Dong-hyeon who has always been a torchlight in the fact-finding movement of Jeju 4·3, Mr. Kim Seok-beom, who visited Jeju at the 70th Commemoration of Jeju 4·3, and Mr. Kim Si-jong, whose poem shined during the performance. The applause appeared to us as our common hope that there will be a day when all of us can gather together to remember Jeju 4·3.

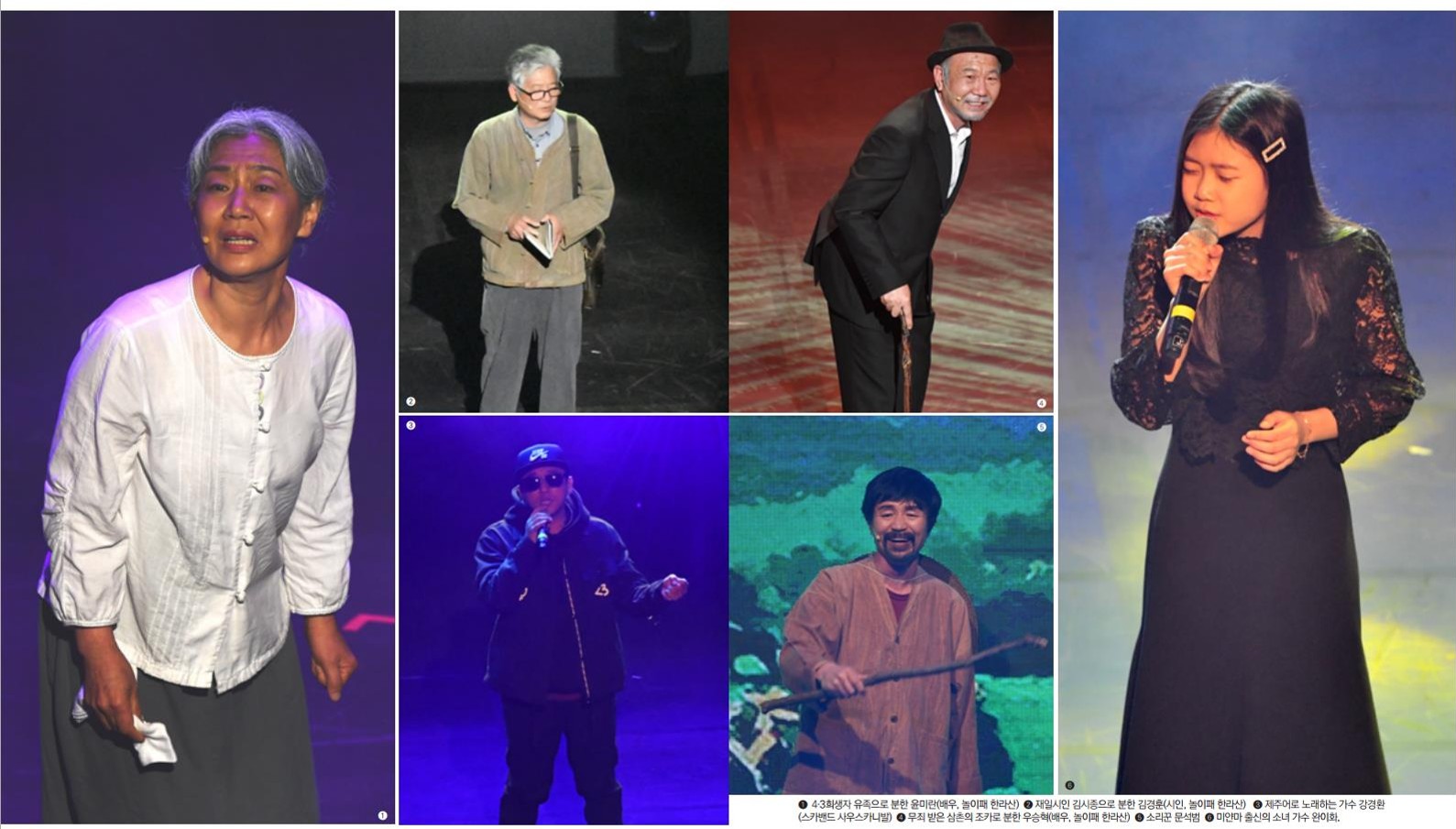

❶ Yoon Mi-ran, an actress with the Hallasan theatrical group, performed the role of a family member of a Jeju 4·3 victim

➋ Kim Gyeong-hoon, an poet with the Hallasan theatrical group, performed the role of Kim Si-jong, a Korean poet in Japan

➌ Kang Gyeong-hwan, a singer from the music band South Carnival, sang Jeju dialect songs

➍ Woo Seung-hyeok, an actor with the Hallasan theatrical group, performed the role of a cousin whose uncle was sentenced not guilty

➎ Moon Seok-beom, a Pansori singer

➏ Wan Yihwa, a Myanmarese singer

Dance crew from the Street Gym Dance Academy and the Phil Music Chorus team performed in the performance’s finale