Testimony of Jeju 4‧3 – Lee Han-jin, a bereaved family member of Jeju 4‧3 victim

Testimony of Jeju 4‧3

Lee Han-jin, a bereaved family member of Jeju 4‧3 victim

Can ‘compensation’ truly atone for years during which the victim was condemned?

Lee Han-jin (born in 1936 in Hwabuk, Jeju, now living in New York, United States)

On Oct. 6, 2023, the 2nd Global Jejuin Festival was held for the first time in four years. Lee Han-jin, president of the Jejudo Association of America, participated in the event and visited Jeju with 20 members from New York. After social activities, Lee and his wife visited the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park. In the park’s Tombstone Park for the Missing, Lee kneeled in front of the marker stone of his two missing brothers and read the verdict that states his siblings were found not guilty after the retrial. As Mr. Lee cried,. the burden that weighed upon him for his entire life was lifted.

As an interviewer and an interviewee, we sat at the conference table on the 4th floor of the Jeju 4‧3 Peace Memorial. We sat face-to-face, with the Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report open on the table between us. For a while, Lee stared at a photo of people taken on May 10, 1948 — the 5·10 General Election. He is about to tell us about his life when he is too afraid to even say “There may be a chance I was taken in this picture.”

Interview arranged by Cho Jeong-hee, head of the General Affairs Team, Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation

Photo by Editing Office

My mother became the head of the household

I am from Beollangdong, Hwabuk-ri. It was the finest village in Hwabuk. My father died before Jeju 4·3. When the incident occurred, there was my mother, me, and my five siblings: my eldest brother, my second older brother, my eldest sister, my second older sister, and my younger sister. We operated commercial ships as a family business for generations. My grandfather and father controlled the business, constantly traveling back and forth between mainland Korea and Jeju on huge ships, so we were well-off. But that was before my father died at sea in an accident. My eldest brother was in Japan, and my second older brother was in Manchuria. My eldest sister was in Seongnae with her husband. My younger sister and I were too young. So, my mother was responsible for the livelihood of the household. My second older sister helped us occasionally, if you can call that luck.

Two brothers, back from Japan and Manchuria

My older brother also worked on a commercial vessel in Japan. I heard he was on a large ship that traveled from Hokkaido to south Shimonoseki. I can only presume that the ship carried coal, and that’s because many Koreans were forced to labor in coal mines in Hokkaido.

After liberation, my older brother moved to Jeju with his wife and children. The ship he was on when he returned to Jeju transported his household stuff and a large amount of rice. Unfortunately, the ship encountered a violent storm in the Korean Strait. The waves were so huge that they nearly engulfed the ship, and the rice bags were soaked. When we cooked, the soaked rice was inedible. We washed it several times, but the salty taste never got better. So, we used the rice to brew alcohol. What a waste! My second older brother also came back from Manchuria after a while.

I saw the liberation of Korea as a second-grade student at Hwabuk Elementary School

Since my grandfather had also taught at Seodang, a traditional Korean school in the local village, I learned the Thousand-Character Classic at a young age, and I entered school a little earlier than my peers. I did not know that then, but later I found out that my friends in class were one or two years older than me. My second older sister carried me on her back when I took the entrance exam. She told me,

Since my grandfather had also taught at Seodang, a traditional Korean school in the local village, I learned the Thousand-Character Classic at a young age, and I entered school a little earlier than my peers. I did not know that then, but later I found out that my friends in class were one or two years older than me. My second older sister carried me on her back when I took the entrance exam. She told me,

“Han-jin, when the teacher draws a pencil and a cup and asks you in Japanese, ‘Korewa nandesuka [これは 何ですか。, meaning what are they]?’ You say, ‘Arewa enpitsudesu [あれは 鉛筆です。, meaning that is a pencil],’ and ‘Korewa koppudesu [これはカップです。, meaning this is a cup]’ Okay?”

The following year, I was in the second grade. On Aug. 15, I witnessed the liberation of Korea. Some say it was a sudden gift from the heavens, but I do not recall anyone crying hurrah out in the streets. I discerned Korea’s liberation when an incident occurred in Gwandeokjeong two years later.

+++ The only picture of Lee Han-seong, Han-jin’s second older brother. Based on this picture, Lee Han-jin believes that his brother studied in Manchuria.

‘Who would pay for the Western-style cakes!’

On March 1, 1947, village folks were excited about a ceremony and its preparation.

The young adults, children, women, and seniors were all happy because the ceremony presented the first time they could celebrate the liberation of Korea.

“Let us crush the pro-Japanese traitors!”

“No to the trusteeship!”

“Who would pay for the Western-style cakes!”

People used bamboo trees to hang wooden placards of slogans. I was too young to know the meaning of “pro-Japanese traitors.” All I cared about was the candies that I got from school. During the Japanese occupation, my school gave students rice cakes. At that time, no one ever said, “Say no to rice cakes!” Why are we saying “No to candies?” Unlike me, who was naïve, my second older brother and the young folk of the village knew that the Western-style snacks would become a debt that we eventually would have to pay back!

People used bamboo trees to hang wooden placards of slogans. I was too young to know the meaning of “pro-Japanese traitors.” All I cared about was the candies that I got from school. During the Japanese occupation, my school gave students rice cakes. At that time, no one ever said, “Say no to rice cakes!” Why are we saying “No to candies?” Unlike me, who was naïve, my second older brother and the young folk of the village knew that the Western-style snacks would become a debt that we eventually would have to pay back!

We tied our headbands, held national flags, and went to Gwandeokjeong. Anyone who could walk went out. The plaza of Gwandeokjeong was packed with people, and my heart was about to explode from the excitement.

+++ Mr. and Mrs. Lee shed tears in front of the monument for lost family members at Jeju 4·3 Peace Park on Oct. 10, 2023.

+++ Mr. and Mrs. Lee shed tears in front of the monument for lost family members at Jeju 4·3 Peace Park on Oct. 10, 2023.

Learning the national anthem of Korea

Our home was spacious. We moved a pile of neatly organized grain from the yard and laid straw mats for people to sit on. My second older brother would gather the village’s young people and teach them the national anthem.

“Until that day when the waters of the East Sea run dry and Mt. Baekdu is worn away, God protect and preserve our nation; Hurray to Korea.”

I was excited to join in and sing along. It was voluntary and a good thing to do, giving up our space to teach the national anthem and Korean language to the young. How can someone call this rebellious? How can one frame sharing joy and happiness as a communist activity? This is why I say that Jeju 4·3 did not begin from the incident in Gwandeokjeong on March 1, 1947, but from the liberation of Korea on Aug. 15, 1945.

+++ A prisoner register of Lee Han-seong, Han-jin’s second older brother (sentenced to death on June 28, 1949). The late Lee Han-seong was executed and secretly buried on Oct. 2, 1949, in Jeongtteureu Airfield (now Jeju International Airport). He was found not guilty in a retrial on Sep. 26, 2023 (top).

+++ A prisoner register of Lee Han-bing, Han-jin’s older brother (sentenced to 15 years in Daegu Prison on July 2, 1949). The late Lee Han-bin was found not guilty in a retrial requested by the bereaved on March 16, 2021.(bottom)

My second older brother survived being gunned down

On May 10, 1947, election day, we climbed Bong-a oreum in Bonggae-ri. My mother, older brothers, their families, and the villagers went together. It was after the election that trouble came to the village. Policemen in plain clothes with clubs were seen. We found out later that they were Northwest Youth League members. When adults started calling policemen in black suits black dogs and soldiers yellow dogs, children began standing guard at the mouth of the village. When the Northwest Youth League began blindly arresting people, the entire town tried to stop them. My older brothers were taken, and I did not know where they had gone.

On a cold, winter morning, I was at home having breakfast with my mother, my second older sister, and my little sister.

“Ma’am!”

A village woman called my mother, so we opened the door. She told us:

“Ma’am! Hurry up. Your son got shot and is in my house.”

My second older brother had survived an execution attempt by the shore and hid in a nearby house. We called one of our relatives who worked as a nurse at a hospital to treat my brother. Luckily, the bullet missed his major intestines, and the wound healed quickly. But this secret of his survival did not last long.

“Tell me where Lee Han-seong is!”

My second older brother, who was supposed to have died in that mass execution, now became prey of the Northwest Youth League.

+++ Lee Han-bin’s prisoner records at Daegu Prison in 1949 (left) and Busan Prison in 1950. It was found that the late Lee Han-bin had been transferred from Daegu Prison to Busan Prison on Jan. 20, 1950. There were no further records indicating his transfer to another prison, which suggests that he was killed in Busan.

Ten sets of suits and ten pairs of shoes

The fortunate survival of my second older brother was the beginning of our family’s misfortune. With the Northwest Youth League constantly searching for my second older brother, we had to leave our home. We toured Bonggae, Doryeon, and Maenchon [now Doryeon 2-dong] daily. One day, my mother, exhausted from the runaway life, bought enough clothes for 10 sets of suits and 10 pairs of shoes. She donated them to the police substation in Samyang. For several days, things were quiet, but a second wave of troubles came.

This time, we had pledge our farm to stop the pursuit. Then the third wave came, and we had no money or farm to give up anymore. When they knew we were broke, they burned down our house. We were taking refuge in the fields as usual and came back only to find that only our house in the village was gone. We couldn’t salvage clothes, let alone a grain of rice.

The deaths of my mother and second older sister

We had to move to my grandmother’s place. There, the Northwest Youth League kept nagging us to find my second older brother. My mother and my second older sister were taken to the Samyang substation every morning and were sent back at night.

“Are you family of Lee Han-seong?”

That morning, a blizzard hit. My mother, who always prepared breakfast for my little sister and me, and my second older sister never returned the night before. That was the last I saw them. My mother’s body was brought home on a cart by her brother. I could see my second older sister’s bloody feet as well and her face, which was covered by a straw mat. My mother was dead, but my sister breathed her last breath after she took a sip of water. They were buried together. I begged to see my mother’s face, but my grandmother refused because she did not want her young grandson to see his mother mutilated. I wonder how sad my grandmother had been when she told me “no.” Her tears are all that’s left when I think of her.

Two brothers turned themselves in and went missing

The long, cold winter came to an end.

The long, cold winter came to an end.

“Han-jin, don’t you miss your older brother? He’s inside the main room. Go see him.”

My older brother was an executive of Minbodan [formerly Hyangbodan, a group initially aimed to be in charge of the general election], and we had no idea he was hiding in our maternal grandmother’s house. The Northwest Youth League ordered him to capture his younger brother, which was an order he could not follow. So, he also became a fugitive. My older brother was hiding in the ceiling of my uncle’s room. In the spring of 1949, he saw a leaflet that said, “Turn yourself in, and you’ll be pardoned.” Eventually, he came out of hiding.

A rumor then spread that those who turned themselves in were locked in an alcohol factory. So, Sanjimul, near the factory, was crowded with people from morning to night hoping to see their detained family members. Because no one knew when the captured would be moved by ships to mainland Korea, they came to Sanjimul in hopes to see their loved ones again, perhaps exiting the facility to take a sip of

+++ Mr. Lee Han-jin’s family gathers for the ancestral rites commemorating Han-jin’s mother, older brothers, and older sisters who were victimized during Jeju 4·3.

water. Mothers were looking for their sons, wives were looking for their husbands, and children were waiting for their fathers. I also roamed around Sanjimul, hoping to see my older brother. There, I heard that my second older brother, whose whereabouts had been unknown for a while, was locked up in another camp near Sanjimul [now the location of the Geonip-dong Community Service Center]. But that was it.

Dreams I did not give up on

After the deaths of my mother and second older sister, I knew nothing about my older brothers. There was only me and my little sister, who was three years younger than me. I was only 11. There was little I could do but study. I was an orphan. I finished my primary, middle, high, and university studies. I lived in Seoul and Japan. Now, I am in the United States. It would have been impossible for me, as an 11-year-old boy, to imagine who I would become.

I moved from one relative’s home to another. I worked at different construction sites as a manual laborer. Despite the hardships, I did not give up on my dream. I was afraid I might get caught in an identification check, but I dreamed of becoming an English teacher in a rural village. I studied English hard, hoping to make my vague dream come true.

I majored in English literature at Jeju National University and considered pursuing a master’s degree. One day, my mother-in-law asked me if I could help her cousin, a Korean resident in Japan, to establish an electronics company. I knew little about electronics but understood that the founders wanted to entrust management to someone trustworthy. So, I got a job in a Japanese electronics company in Seoul. Fortunately, the company’s business was successful, and I was encouraged to challenge for more. I got a job at SONY.

Overcoming the guilt by the association system

Working at SONY headquarters in Japan was a turning point in my life. I was good at English conversation, which helped me move to SONY’s New York branch. Moving to the United States was a natural process. And, my wife helped a lot.

She was a central public official working for the women’s community. Her job was to guide prostitutes to move onto a new life, so her tasks were related to those of the police department. Her career and position facilitated obtaining a visa. But at the time, it wasn’t easy to get a visa issued.

After settling in Brooklyn, New York, I started a large supermarket. There were moments of despair and frustration in my life outside of Korea since I had no one to depend on. However, this life was also a chance for me to begin anew, and put behind me the tragedy my family experienced back in Jeju. So, I challenged myself to do better. Now, the business has stabilized. I have two children who grew up to become prosperous [Mr. Lee’s son and daughter-in-law are cancer specialists. His daughter majored in international law, and her husband is a constitutionalist and a professor at Cornell Law School).

+++ Mr. Lee Han-jin performs ancestral rites in the United States. His son-in-law and daughter-in-law also participate in the ritual.

+++ Mr. Lee Han-jin performs ancestral rites in the United States. His son-in-law and daughter-in-law also participate in the ritual.

Unconditional benevolence and the unhealed trauma

I still remember and can recite all the English poems I learned in university. If I had entered the master’s degree program as I had planned, I might have become an English literature professor. Many who knew me well told me to write professionally. However, without clarifying my second older brother’s record, I could not reveal myself nor say anything about what had happened.

As my business in New York grew successful, I was contacted by numerous people. Korea seemed generous to a successful businessman. Nevertheless, I could not risk myself by participating in social activities, including voluntary charities. I had to find anonymous ways to help others, which is the idea of helping others unconditionally. It has something to do with Mujusangbosi [a Buddhist notion of unconditional benevolence], but not because I am a great man.

My whole life, my family’s record was my weak point. I had to censor myself, doubting whether I would be misunderstood for providing sponsorship or becoming involved in group activities. I was constantly worried about and feared repercussions from the guilt-by-association system. If this is what you call trauma, then my trauma is far from being cured.

Can compensation truly atone for the time during which the victim was condemned as a communist?

The first thing I do every morning is search news on Jeju 4·3. As I read all the articles and materials on Jeju 4·3, I still see some people who, at official meetings, use terms like “the Reds of Jeju 4·3.” Don’t say that so easily! That’s too simplistic and dichotomous. Be that as it may, if we want to call those who were involved in the communist ideological activities “Reds,” we also have to answer the question, “What about the innocent people killed who knew nothing about the ideological conflict?” The reasons for their deaths should all be clarified, one by one, to end this nonsense where the victims, who died on false charges, are denounced as “Reds.” Let’s be honest; the truth of Jeju 4·3 was covered by the act of condemning us as communists. Even now, there are still things that those who condemn us want to hide. Some still want to cover up the truth even though there are steps being taken to resolve Jeju 4·3. This is not about the money. Justice should come first. Then the state’s responsibility should follow. Compensation shouldn’t be a primary goal. We still have much to uncover. This is an ongoing issue.

My two brothers were announced not guilty through a retrial. Had I stood in the court, I would have asked the judge, “Can the word ‘not guilty’ conclude everything? Can the single statement recover the time during which the victim was condemned as a communist?”

I hope the falsely charged victims have their honor restored. Without it, it is meaningless to define Jeju 4·3. It is like an answer without a question. Jeju 4·3 can be resolved only when every person in Korea can acknowledge it as “the deaths of innocent Jeju people at the hands of the state.”

– Jeju 4·3 activities

– Jeju 4·3 activities +++ Poet Kang Dukhwan talks to Jang Yoon-sik, head of the Memorial Project.

+++ Poet Kang Dukhwan talks to Jang Yoon-sik, head of the Memorial Project.

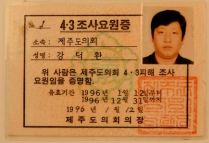

+++ The signboard-hanging ceremony is held for the reporting of Jeju 4·3 victims (top). The Jeju 4·3 Special Committee investigates the Gujwa area (bottom).

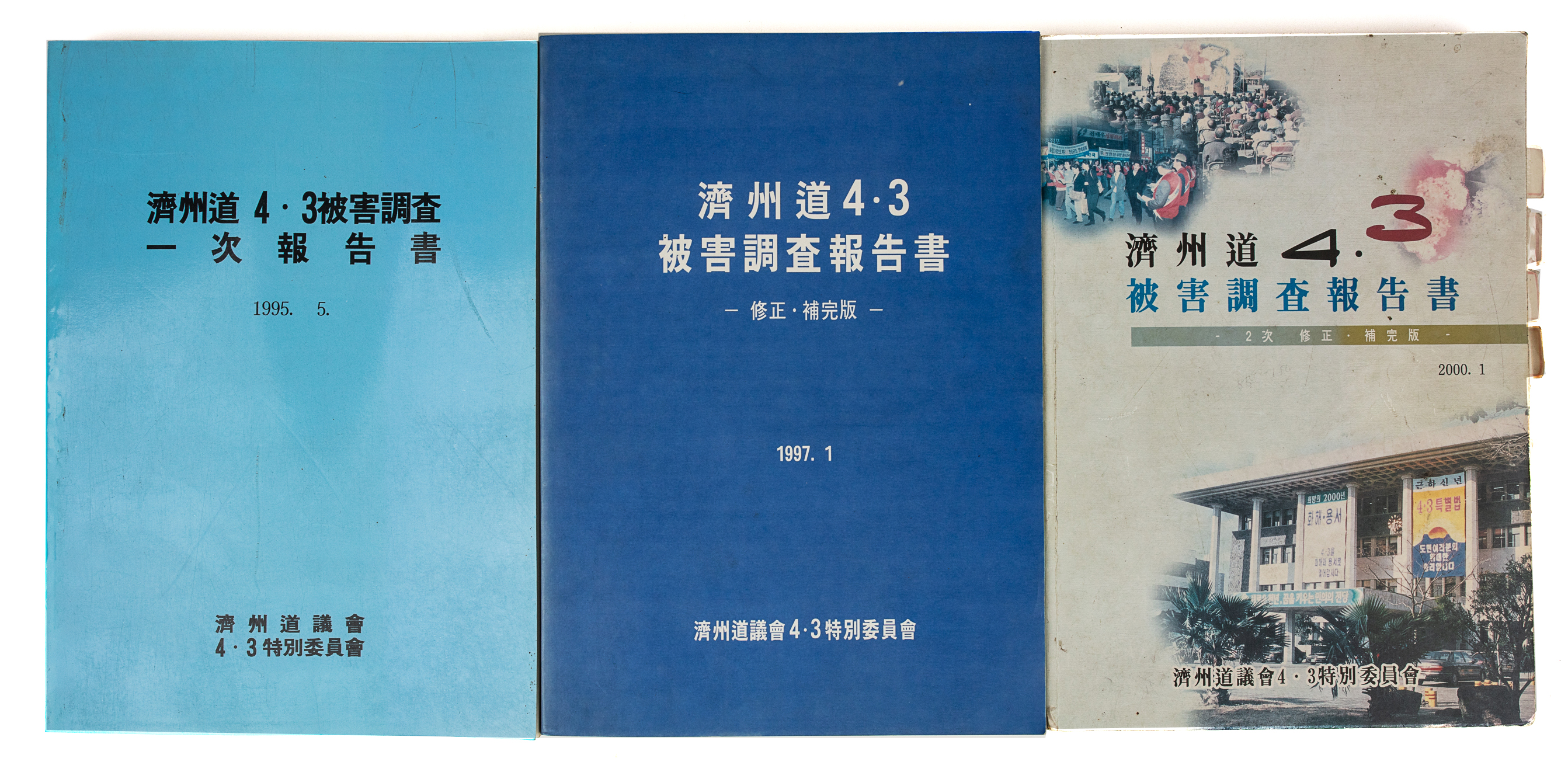

+++ The signboard-hanging ceremony is held for the reporting of Jeju 4·3 victims (top). The Jeju 4·3 Special Committee investigates the Gujwa area (bottom). +++ Jeju 4·3 Damage Investigation Report published by the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee, Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council.

+++ Jeju 4·3 Damage Investigation Report published by the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee, Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council.

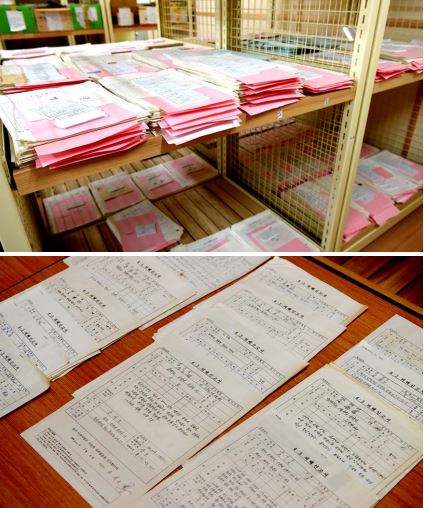

With the elevation of the status of Jeju Province to that of the Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, the number of local council members increased. There were not enough legislative chambers and meeting halls. By the time, the Jeju 4·3 documents had been stored in the archives of the provincial legislature, and it was decided to use that space for other purposes.

With the elevation of the status of Jeju Province to that of the Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, the number of local council members increased. There were not enough legislative chambers and meeting halls. By the time, the Jeju 4·3 documents had been stored in the archives of the provincial legislature, and it was decided to use that space for other purposes.

+++ A Jeju 4·3 story-telling program.

+++ A Jeju 4·3 story-telling program. +++ A kinesitherapy program.

+++ A kinesitherapy program.

+++ A horticultural healing program (top).

+++ A horticultural healing program (top).

+++ An healing outreach program.

+++ An healing outreach program.