Achievements and Contributions – Poet Kang Dukhwan

Resolution of Jeju 4‧3 is a valuable achievement that Jeju islanders have made together

Poet Kang Dukhwan

– Jeju 4·3 activities

– Jeju 4·3 activities

(Former) Policy Researcher, Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council

(Former) Member of the Jeju 4·3 Working Committee, Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council (Planning Subcommittee Chair)

(Former) Board member, Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation (Subcommittee Chair)

(Current) Chairman, Steering Committee for the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park and the Jeju 4·3 Peace Memorial Hall

(Current) Advisor to the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee, Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council

(Current) Member of the Jeju 4·3 Peace and Human Rights Education Committee, Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Office of Education

– Literary associations

(Former) Member and chairman of the Steering Committee, Jeju Literature Center

(Current) Chairman, Jeju Literature School

(Current) Director, Association of Writers for National Literature

(Current) Director, Jeju People Artist Federation

(Current) Chairman, Jeju Writers’ Association

– Compilations

- Lead author, Jeju 4·3 Damage Investigation Report (3 volumes, Jeju Provincial Council)

- Lead author, Jeju 4·3 White Book of Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council (Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council)

- Co-author, Jeju 4·3 Historical Sites – In Search of Lost Villages (Hakminsa)

- Co-author, Jeju 4·3 Records of Human Rights Violation – Victims of Unlawful Imprisonment Returning from the Grave (Yukbi)

- Co-author, Jeju 4·3 Literature Map Ⅰ, Ⅱ – Jeju City, Seogwipo City (Jeju People Artist Federation)

- Co-author, 70 Years after Jeju 4·3 – From Darkness to Light (Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation)

- Co-author, Manbengdi, the Wind of Peace (7.7 Manbengdi Bereaved Families Association)

- Co-author, Jeju 4·3 Incident Follow-up Investigation Report (Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation)

- Co-author, History of Jeju 4·3: A Photographic Archive (3 volumes, Jeju 4·3 Memorial Project Committee)

- Co-author, Stories of Jeju 4·3 in Nohyeong-dong (Nohyeong-dong Resident Autonomy Committee)

– Books of poems

- Ride of the Living Dead (1992, Oreum Publishing)

- That Winter Was Cold (2010, Punggyeong)

- On an Island, Even the Wind Is a Friend (2021, Life Chang)

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the launch of the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee of the Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council. The committee took the responsibility for receiving the reports on Jeju 4·3 victims, conducted investigations at the provincial council level, and published the Jeju 4·3 Victims Investigation Report (three volumes in total). The committee members played a key role in unifying the separately performed memorial ceremonies for Jeju 4·3 victims, which had been a source of division and conflict in the local community. It was also the provincial council’s Jeju 4·3 Special Committee that urged the national government and the National Assembly to resolve Jeju 4·3 through the enactment of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act.

The following article is the record of our interview with Kang Dukhwan, a poet who has worked on the investigation of Jeju 4·3 from the onset of the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee and is still working to reveal the truth about Jeju 4·3 and restore honor to the victims. <Editor>

Interview and Arrangement by Jang Yoon-sik, Head of the Memorial Project Team

Photographs by the Editing Office and Photographer Kim Ki-sam

When and how did you recognize Jeju 4·3?

I am from Nohyeong, a Jeju village that saw the biggest number of residents killed during Jeju 4·3. Growing up, I found it quite ordinary to hear the term “Jeju 4·3.” A family in my neighborhood lost ten of its members in a massacre. When I was attending ancestral rituals for holidays or memorial services, the food placed on the table used to create a heavy atmosphere, rather than satisfying my hunger. In my middle school years, I would get chilled to the bone when walking past the pine tree field in Doryeong Maru, one of the sites where many residents of my village were killed during Jeju 4·3. Under these circumstances, I have felt myself somewhat bound to the tragedy since childhood.

When I was little, I thought we had no Jeju 4·3 victims in our family. Nobody had ever told me that we actually do. It wasn’t until I started working for the resolution of Jeju 4·3 that I learned that my grandfather lost his life during Jeju 4·3. My father’s step brother was also sent to a prison on the Korean mainland and died there during his prison term. However, my father was later adopted to a different family and registered on their family register. So, I’m not recognized as a victim’s bereaved family member. Well, it took me so many years to learn and understand all these stories.

What inspired you to engage in the activities related to Jeju 4·3?

I entered the university in 1980, the year of the so-called “Seoul Spring” when people were eagerly looking forward to democratization. It was when I read novels written by Hyun Ki-young. In fact, I was more impressed with The Crow of Doryeong Maru City Plaza, rather than with Sun’i Samch’on which relates to the Bukchon Massacre. The Crow of Doryeong Maru City Plaza tells a story of my neighborhood featuring places that sounded familiar to me. It was shocking to read a novel in the Jeju language for the first time in my life. I also learned that the novelist and I came from the same neighborhood after reading the book.

In college, I studied Jeju 4·3 with upper and lower grade students in a literary club and tried to create a work. The first poem I wrote in 1980 with the theme of Jeju 4·3 was titled “Oleander in Chonamdongsan Hill.” Looking back, I was pretty condescending in the poem, just beating around the bush. In 1982, intelligence authorities caught me when my club members and I were working on the script for a theatrical play, titled On the Night of December 18 on the Lunar Calendar, which was an adaptation from Sun-i Samch’on. The entire script was confiscated, with the performance canceled as a result. I also remember that on April 3, we gathered in my rented room where we prepared a table of offerings for the Jeju 4·3 victims and held a memorial service by reciting prayers. When poet Lee San-ha released a long poem titled Hallasan Mountain, we circularized and studied it together.

After graduation, a heightened social mood to discover the truth about Jeju 4·3 was created in light of the June Democratic Struggle of 1987. The Jeju Cultural Movement Council was established, and I joined its affiliate organization, the Jeju Youth Literary Society. I participated in the investigation of Jeju 4·3, creation of collaborative works, and the exhibition of illustrated poems, broadening my awareness of Jeju 4·3. Additionally, I worked as a correspondent for a magazine Jeju Monthly and continued to write investigative pieces.

+++ Poet Kang Dukhwan talks to Jang Yoon-sik, head of the Memorial Project.

+++ Poet Kang Dukhwan talks to Jang Yoon-sik, head of the Memorial Project.

Addressing the report of victims at the local Jeju 4·3 Special Committee is another Jeju 4·3 movement

This year, the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee of the Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council marks the 30th anniversary of its founding. Please tell us about the formation and significance of the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee.

The local council of Jeju had the experience of addressing Jeju 4·3 in 1952, when the first provincial council was established. As is well-known, it was during the Korean War, so the activities were to budget for the destruction of communist guerillas. During the April Revolution that began on April 19, 1960, the National Assembly ran the Civilian Massacres Investigation Group, and the Jeju Provincial Council cooperated with it. After the May 16 coup in 1961, the local council itself disappeared under the military regime and the revitalizing reforms system. And the investigation of damage and the discovery of the truth submerged under the surface.

+++ The signboard-hanging ceremony is held for the reporting of Jeju 4·3 victims (top). The Jeju 4·3 Special Committee investigates the Gujwa area (bottom).

+++ The signboard-hanging ceremony is held for the reporting of Jeju 4·3 victims (top). The Jeju 4·3 Special Committee investigates the Gujwa area (bottom).

In 1991, the local councils were reinstated after a 30-year hiatus. At the time, candidates running for the election sometimes made campaign pledges to resolve Jeju 4·3. I think that it resulted from the combination of achievements of the June Democratic Struggle of 1987 and the transformative period toward democratization that followed. Of course, there were other achievements such as novels by Hyun Ki-young, papers by John Merrill, and books by Kim Bong-hyeon and Kim Min-ju that came out intermittently during the previous military regime. But we were not able to talk freely about Jeju 4·3 at the time. Books about Jeju 4·3 were banned from sale, and activist Kim Myeong-sik was imprisoned. It was a time when we spoke out through difficulties. After that, the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute was founded, and the Jeju 4·3 movement began in various fields, with the historical case covered by newspapers and broadcasters. These were followed by the exhumation of the remains inside Darangshi Cave, exhibitions of historical paintings on Jeju 4·3 by Kang Yo-bae, and archiving of various testimonies. Under these circumstances, the local council, a representative body formed in 1991, naturally began to address Jeju 4·3 issues. And the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee was launched on March 20, 1993. Jang Jeong-un, then chairman, and Kim Young-hun, chairman of the steering committee (who later also served as chairman of the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee), played an active role in the process.

You were one of the first members of the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee to play a key role in accepting the report on the Jeju 4·3 victims and the working-level investigation in the Jeju 4·3 Special Commission. What was the atmosphere like in the early days?

I think I should first tell you why the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee of the Jeju Provincial Council opened the office for the reporting of Jeju 4·3 victims and investigated the reported cases. In November 1993, the Jeju Provincial Council requested the National Assembly for the enactment of a special act and the formation of a special committee to resolve Jeju 4·3. And the National Assembly responded by asking, “You say you need a special committee and a special act, but based on what estimation of the victims?” We didn’t know the number of victims. The lawmakers didn’t know, and the local council members that had made the request didn’t know, either. Our request was based on the vague estimation of 30,000 to 80,000 victims, and it didn’t work. As it wasn’t likely to work, we decided to at least do some basic research. And on Feb. 7, 1994, we opened the office for the reporting of Jeju 4·3 victims.

We set up the desk on the 4th floor of the provincial council building, with only two staff members. I received the reports while the female assistant organized the reports. As soon as the office was launched, the reports started pouring in. It was hard for the two of us to manage the workload, so we started to do regional investigations with investigators appointed to each area. The provincial council members recommended 17 investigators, one from each constituency. The investigators did research in their respective regions and made a monthly report. However, even with the organized investigation system, the initial effect was less than expected. So, we complemented the process by appointing four additional investigators and conducted a thorough investigation. In April 1995, the first draft of the Jeju 4·3 Damage Investigation Report came out. The report included the list of about 12,000 victims.

The task must have been very difficult at the time.

Indeed. Not just the lack of the investigators, we experienced so many difficulties during the on-site investigation in different regions. For example, when you visit rural areas during the day, people would have gone to the field or orchard for work. It was difficult to make an appointment in advance because there were no cell phones at that time. And if it were a little after dinner time, they would have turned off the lights to sleep. People were also afraid of investigators knocking on the door and saying, “We are here to take reports on Jeju 4·3.” There were also cases of dog bites during the investigation.

And memory has its limitations. Many people failed to clearly remember the exact year or month their loved ones died. To estimate the time, we used to ask, “Was barley in season?” or “Was it the harvest time for potatoes or beans?” And even if we were able to estimate the time, many people often misunderstood the preliminary arrest during the Korean War, because they remembered Jeju 4·3 as a war. It was also difficult to organize the dates because most of their testimonies were based on the ancestral rituals, which were calculated following in the lunar calendar. Some even testified that there were no victims in their families because of the wrong assumption that only those who were shot would be recognized as victims.

There were many cases where the names of victims were incorrect. Back then, we were not allowed to request copies of family registers or other documents that could identify the victims. It was before the legal grounds for the investigation were prepared. Therefore, we had difficulties identifying the victims when their families reported them under names used in childhood or registered differently in family registers. Some families even refused to report the deaths of young family members, saying the death of a child might mean bad luck to the family.

We also had to deal with those who were infuriated, saying, “What’s the point of investigating Jeju 4·3 now?” Some people spoke nothing of their damage at all because their children were government employees and they were worried about their descendants. Lots of people were reluctant to report the cases of victims for a variety of reasons. Sometimes, I would visit a family knowing through prior research that there was a victim in the family. But when they denied it, I couldn’t force them to report. Returning to the office, I felt helpless.

Were there any attempts to cajole or intimidate the committee members?

Once, I was contacted by the public security authorities, demanding that I send them the list of reported cases. I said, “I can’t do that. The victims and survivors are already frightened of reporting their cases, and I can’t tell them that this list will be reported to the intelligence agencies.” I kept saying, “I can’t give you the list even if I have to quit my job.” Later, they compromised to request the number of people that had been reported, and I closed the case by letting them know the number of reported cases.

There were many similar attempts as made by the intelligence agencies. After all these twists and turns, the first report on the damage came out in 1995, based on which we demanded that the government and the National Assembly discover the truth about Jeju 4·3. After the report was published, the police visited the committee for investigation. They said that the names on the report were incorrect, so as the ages. Of course, the names could be incorrect. Why? We didn’t have the authority to read the family registers. We also noted in the report that the list of missing victims includes the list of alleged victims, of which the records were based on the survivors’ testimonies of their deaths. It was for proper investigation in the future, but they criticized that we did a sham investigation.

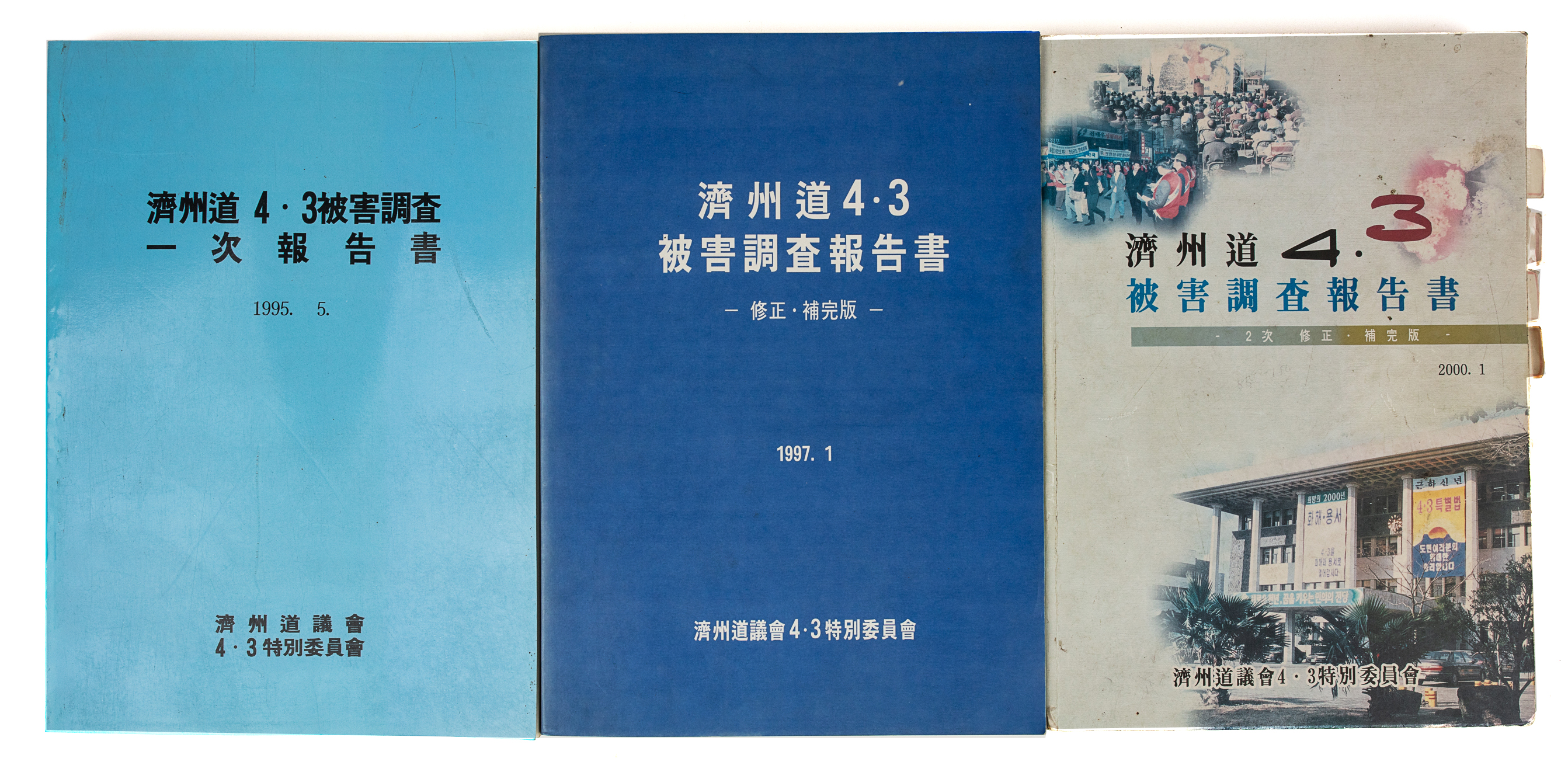

+++ Jeju 4·3 Damage Investigation Report published by the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee, Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council.

+++ Jeju 4·3 Damage Investigation Report published by the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee, Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council.

There was personal repression against me as well, asking “Why are you receiving false reports?” or “Why are you distorting the truth about Jeju 4·3?” They filed a complaint against all the articles I wrote in the newspapers or magazines, claiming that it’s the distortion of the truth. Some even accused me of defaming the victims, pointing out the typos in the report.

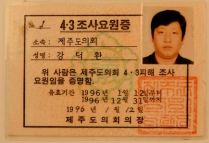

+++ A Jeju 4·3 Investigator’s ID card and investigation note.

In 1997, I was also the subject of a police reference investigation. The director of the documentary film about Jeju 4·3, “An Outcry That Never Sleeps: Jeju 4·3 Resistance,” had been detained for violating the National Security Act. They suspected that the director had received funding from the pro-North Korean group named the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan. As a member of the film production team, I was subject to investigation as well. But their suspicion was completely untrue, and they had no evidence. So, I was soon released. It was a bad enough time.

I also remember finding the victim with the help of the police, with which we used to maintain a tense relationship. The victim was a resident of Bukchon-ri, but he was not originally from the region. He had moved from outside to fire earthenware. According to the testimonies of his neighbors, five to six members of his family died during Jeju 4·3. But that was the only clue we had about their deaths. Then we traced the case through the police’s information network, and figured out that he was from Jeollanam-do Province.

Despite many challenges, the activities must have been very rewarding.

Above all, the official acceptance of the report on the damage by the provincial assembly was an opportunity for the bereaved families to heal the wounds that they had been suppressing and suffering from the Red Complex. When they came to report, they complained the injustice caused by Jeju 4·3 and the hard life they had been living. I could never neglect to listen to their complaints. It was very rewarding for me to be able to listen to them.

Since 1994, long before the enactment of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act, a joint memorial ceremony was performed through the mediation of the Jeju Provincial Council. And it was rewarding that the list of victims on the plaque was based on the list we researched. I think the mediation for the joint memorial ceremony was a great achievement of the Jeju Provincial Council, which was achieved through the cooperation of the bereaved families and the people of Jeju. It is believed to have helped the integration of the bereaved families and the formation of the mood for reconciliation and mutual prosperity.

The three volumes of Jeju 4·3 Damage Investigation Report, each published in 1995, 1997, and 2000, served as important base data for the subsequent administrative treatment of reports on Jeju 4·3 victims under the Jeju 4·3 Special Act. To my knowledge, the books helped identify victims that have yet to be registered. This is also very rewarding.

+++ Jeju 4·3 pilgrims chant slogans in front of the National Assembly.

What stood out to you while working in the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee?

In 1999, there was a national pilgrimage and visit to the National Assembly by members of the four city and provincial legislatures of Jeju Province to raise awareness of Jeju 4·3 and call for the enactment of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act. We felt an implicit urgency that what was done in the 20th century should not be carried over into the 21st century unresolved. All of the relevant organizations joined the pilgrimage. This moved the National Assembly, and later that year, the Jeju 4·3 Special Act was passed at the National Assembly, which was a tremendous momentum builder.

Moreover, the documents proclaiming martial law concerning Jeju 4·3 were discovered by the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee and reported to the media. I also remember activities such as submitting the Report on the Victims of Civilian Massacres to the National Assembly, securing data regarding refugee resettlement, and publishing a partial translation of the U.S. military intelligence report during the Jeju 4·3 period. In addition, we tried to share the pain of Jeju 4·3 through the exchanges with Okinawa and Taiwan, which experienced similar cases, and with those working to resolve the cases related to the Gwangju Democratization Movement, massacres in Geochang and Daejeon Gollyeong-gol, and March 15 Masan Uprising. Among the roles of the local council is the right to enact municipal ordinances. We tried to prepare solutions to the Jeju 4·3 issues by enacting the Ordinance Concerning the Preservation and Management of Jeju 4·3 Historical Sites, Ordinance Concerning the Subsidization of Living Expenses for Surviving Victims and Bereaved Families Related to Jeju 4·3, Ordinance Concerning the Promotion of Peace Education Related to Jeju 4·3, and Ordinance on the Designation of April 3 Memorial Day as a Local Holiday.

You must have met a lot of people through your activities on Jeju 4·3. Any memorable people or events you could refer to?

I’ve met so many survivors and bereaved families, all of whom shared with me valuable testimonies of their unfortunate memories. I was particularly impressed by those who had independently investigated the damage caused to their villages even before the enactment of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act, or going further, even before the launch of the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee. They did so with great courage. I remember Kim Yang-hak, who wrote The True Record of Jeju 4·3 in Tosan-ri, and Moon Ki-bang, the author of Josu-ri Records for Posterity. There were Hong Sun-sik in Bukchon-ri and many others in Iho-ri’s Odorong Village and Pyoseon-myeon’s Gasi-ri. I believe that they were all driven by a sense of urgency to document the unjust victimization and make it known to posterity. In addition, our activities in the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee were greatly influenced by the media coverages, including reports by the Jemin Ilbo’s Jeju 4·3 reporting team and the special reports on Jeju 4·3 aired in series by Jeju MBC.

Reports of Jeju 4·3 victims archived at the provincial council represents the souls of 12,000 residents

The proposal to inscribe the documentary heritage of Jeju 4·3 on the UNESCO Memory of the World list has been passed in Korea and will soon be reviewed by UNESCO. The Jeju provincial council’s records of Jeju 4·3 victim reports have been included in the heritage list. Please tell us about the archiving and transfer of the documents.

With the elevation of the status of Jeju Province to that of the Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, the number of local council members increased. There were not enough legislative chambers and meeting halls. By the time, the Jeju 4·3 documents had been stored in the archives of the provincial legislature, and it was decided to use that space for other purposes.

With the elevation of the status of Jeju Province to that of the Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, the number of local council members increased. There were not enough legislative chambers and meeting halls. By the time, the Jeju 4·3 documents had been stored in the archives of the provincial legislature, and it was decided to use that space for other purposes.

Around that time, the Jeju 4·3 Special Committee relocated its office into the old Bukjeju-gun Office. I insisted that I would take charge of the documents and kept and managed them in the hallway. The documents contained personal information, and they didn’t seem to be strictly protected. There were 12,000 reports archived at that time. To me, they were like the souls of the deceased. That’s why I tried to keep the reports safe, thinking that I would carry them with me even if it meant losing my life. I even kept all the pickets, flags, banners, vests, and shoulder straps that we used in the campaign.

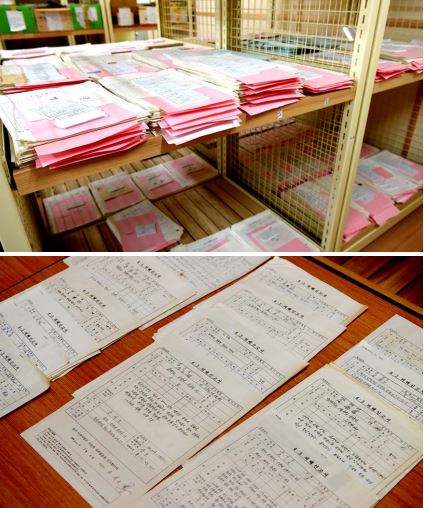

+++ A stack of reports on damage due to Jeju 4·3.

After the enactment of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act, we saw the opening of the provincial Jeju 4·3 Office and the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park. So, we transferred the archived materials to them, in the form of a donation by the provincial council. They are now safely stored in the repository of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, where they are kept at constant temperature and humidity.

It would be very rewarding for me if they are included in the documentary heritage recognized by UNESCO. Of course, even if not for me personally, the UNESCO inscription would be very meaningful for addressing Jeju 4·3 on a global scale.

When it comes to regrets about the materials, we were more focused on getting the report done at the time, and we failed to take time to record the detailed stories of survivors or bereaved families. To my regret, many of those that could testify so vividly 20 years ago passed away or have foggy memories due to old age now.

You are still involved in addressing Jeju 4·3 issues, not only as a former member of the Jeju 4·3 Working Committee, but also as a poet and as the chairman of the Jeju Writers’ Association. How do you approach your work?

One of the reasons I quit my job as a policy researcher at the Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council in 2018 was because I wanted to write more. Then I published a book of poems, authored a book about Jeju 4·3 stories of my hometown. I am now the president of the Jeju Writers’ Association, working for expanded exchanges with writers’ associations in other regions. Jeju is not the only place that is suffering. It is necessary for writers’ associations to keep in mind that there are innumerable cases that remind us of the importance of peace, such as human rights violations at home and abroad committed in the past. By building solidarity between regions with similar painful experiences, we can make literary practices to prevent them from happening again. The Jeju Writers’ Association has been networking or considering the request to network with writers in Gwangju, Daegu, Busan, and especially recently, Gyeonggi-do, Chungcheongbuk-do, and Daejeon, as well as foreign writers in Vietnam, Taiwan, Okinawa, and Mongolia. In addition, the Jeju Writers’ Association has held exhibitions of illustrated poems at the gate post of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park for 20 years. Earlier, it was for local writers based in Jeju, but now we are exhibiting the works of poets from all over the country. I think that Jeju will become a sanctuary for peace and human rights in a true sense by embracing the pain of other regions.

I also want to cover in literature little-known clashes between the armed guerilla forces and the counterinsurgency forces, as shown in Sallani Oreum, Noru Oreum, Muljangori Oreum, Miaksan Oreum, Hansugigot Forest, and Nogajiak Oreum. Shouldn’t literature take the lead in addressing these?

This year, I went on a literary trip to the Daejeon National Cemetery and Ganghwa Island bordering North Korea. Those who came to suppress Jeju Island are buried in the Daejeon National Cemetery. I wanted to think about how to view these people from a literary perspective.

What do you think are the remaining challenges for the resolution of Jeju 4·3?

“Discovering the truth about Jeju 4·3, restoring honor to the victims, punishing those responsible, paying reparation and compensation, and inheriting the spirit.” These are the keywords for addressing the wrongdoings committed in the past. But punishing the perpetrators is a very difficult task. Rather than simply holding Minbodan [civilian guard corps], police, or soldiers on the front lines responsible, we must clearly identify the real perpetrators behind the scenes.

We also have to think about the fact that even in the fully revised Jeju 4·3 Special Act, we have failed to change our smothering stance of excluding many of those affected from officially recognized victims.

As a writer, I think there remain a lot of issues to be discussed, specifically over how to build a social consensus against the forces that vilify Jeju 4·3 and attempt secondary victimization. And, given that the ultimate goal of resolving Jeju 4·3 is to overcome the division of Korea, promote human rights, and realize world peace, Jeju needs to be able to contribute to this ultimate goal.

Do you have any final comments to share with our readers?

On April 3, 1994, the Statement for Healing the Wounds from Jeju 4·3 was announced in the name of the chairman of the Jeju Provincial Council. It reads, “Importantly, resolving Jeju 4·3 must be premised on mutual forgiveness and reconciliation because all Jeju residents are victims in a sense.” This was to urge Jeju residents to form a united front to solve Jeju 4·3 issues.

Otherwise, it would create division between neighbors, between relatives, between neighborhoods, and between villages. Of course, if someone did something wrong, he or she should apologize. And, in turn, the other party should be able to accept the apology. This is how we can move toward a unified Jeju community.

The epitaph of the Memorial Tower in Bukchon-ri delivers novelist Hyun Ki-young’s message: “We erected this lasting, unforgettable stone monument so as to forgive but not forget.” It is also inscribed with the phrase that reads, “We erected this stone monument in the name of peace… because we deserve to shout peace with dignity.” These are the words that have struck me.

I believe that consoling the souls of the victims should not take the form of oblivion, which aims to lay them at eternal rest and close the case. Rather, it should be an opportunity to strengthen our determination to not repeat the dark past and to use the lessons learned as an impetus for a new chapter in history.

So far, the Jeju 4·3 movement has achieved a lot to get to the point where compensation is being made for the victims. There were so many people who spared no effort in the process, including victims’ bereaved families, the people of Jeju Island, and conscientious people from all over the country. We could make it because activists in Jeju 4·3-related groups, journalists, artists, college students, provincial council members, and victims’ families in Korea and overseas have all expressed the shared commitment that Jeju 4·3 must be resolved.