“Jeju Is Alive”… Jeju 4·3 Memorial Ceremony Resumed in Tokyo, Japan, after Three Years

Heo Ho-joon

Senior Correspondent with The Hankyoreh

[Koh Hee-bum, chairman of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, gives a congratulatory speech at the Jeju 4·3 Memorial Lecture and Concert in Japan.]

Jeju 4·3 Memorial Lecture and Concert held on June 20 in Arakawa-gu in Tokyo, Japan

“Bones covered in mud / start talking quietly / Deep sorrow / as if inhaling the earth / tries to revive / from under the humid ground / Why the sound / didn’t reach / and disappeared / Mud-covered / shoes / how far did you / try to walk / Broken eyeglasses / what did you / try to see there / God / if you exist / why our souls / why our brothers and sisters / were not saved / Jeju Island cries / I’m alive / it screams”

[Park Bo (left) and Ha Young-su, second-generation Koreans in Japan, are presenting a memorial music performance for Jeju 4·3.]

Park Bo, a second-generation Korean musician in Japan, filled the stage with his performance as if he were screaming. The audience that packed the event hall held their breath and focused on his singing. When Park first performed his own song “Jeju 4·3,” applause erupted from the stands.

At 6 p.m. on June 20, “A Memorial Lecture and Concert on the 74th Anniversary of Jeju 4·3” (hereinafter called the Jeju 4·3 Memorial Lecture and Concert) was held at ART HOTEL Nippori Lungwood in Arakawa-gu in Tokyo, Japan. The event was hosted by the Tokyo Society for Jeju 4·3 (hereinafter called the Tokyo 4·3 Society). Although it had been suspended for three years since the outbreak of the COVID-19, the stands were full of people just like in previous years. Since 1998, the Tokyo 4·3 Society has held a memorial service, lectures, and concerts every April to let Japanese society know about Jeju 4·3. While the Osaka Society for Jeju 4·3 commemorates the anniversary of Jeju 4·3 with a focus on the memorial service, the Tokyo 4·3 Society places more weight on public events such as lectures and concerts. The events hosted by the Tokyo 4·3 Society are widely recognized by Japanese citizens, attracting more Japanese participants than Koreans living in Japan.

According to officials of the Tokyo 4·3 Society, they took lots of issues into consideration before making the last-minute decision to hold a face-to-face event this year, and had to prepare and promote the event with less than two months left left. However, the visitors showed keen interest in the memorial event, which was held for the first time in a while. The program lasted more than three hours, but few people left before the closing of the event.

It was in 1988 on the 40th anniversary of Jeju 4·3 when Jeju 4·3 was publicly addressed for the first time in history. The first public events were held under the theme of Jeju 4·3, not just in Jeju and Seoul but also in Tokyo, Japan. With this event as momentum, the memorial service for the victims of Jeju 4·3 came to be established in Japan.

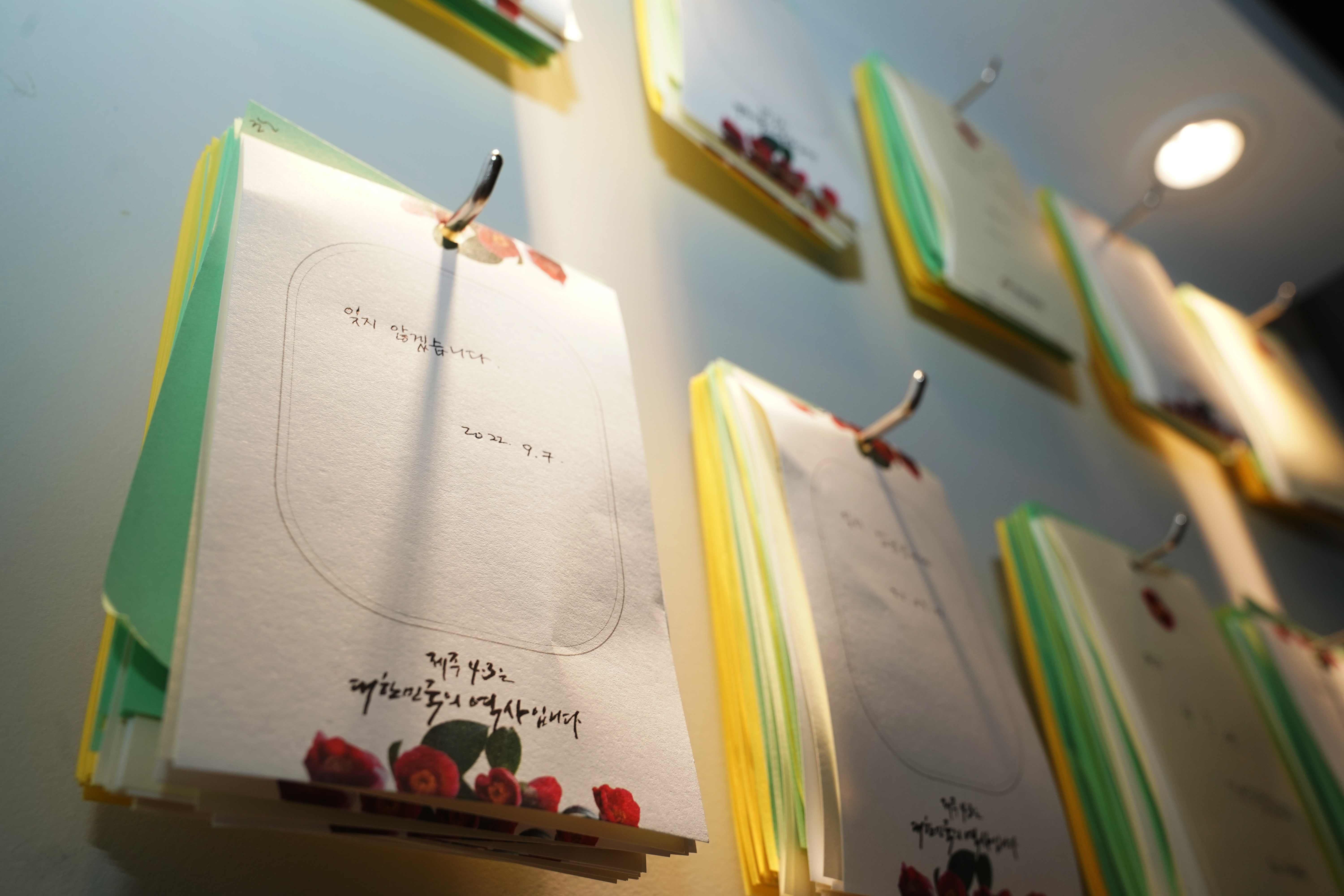

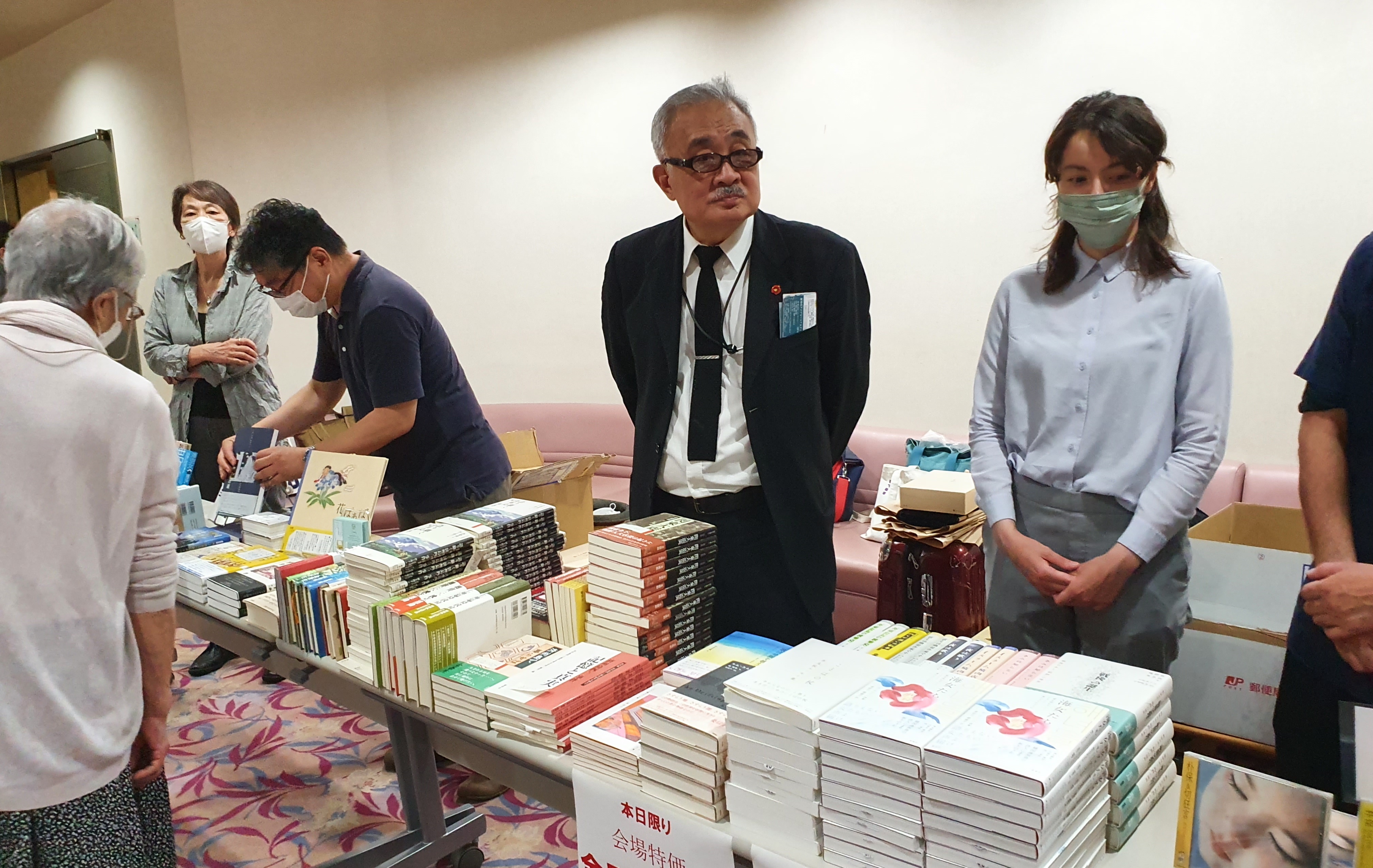

[At the entrance of the venue, a display stand was prepared to sell books and other materials related to Jeju 4·3.]

[The audience danced to the music during the Jeju 4·3 Memorial Ceremony and Concert.]

350 people visit the hall with 250 seats, mostly Japanese willing to learn about Jeju 4·3

The display stand for Jeju 4·3-related books and music albums at the entrance of the venue was crowded with visitors as the event was about to start. Some met for the first time in a while and asked after each other, and some welcomed the group of visitors from Jeju.

Oshio Takeshi, an activist at the Arakawa-gu Research Society for the Protection of the Peace Constitution, said, “I learned about this memorial event when I was invited to a research meeting led by Ko Yi-sam, who runs the publishing company Shinkan Sha. This is my second time to attend the memorial service. It is impressive that many Japanese came even during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Another participant named Hatori Mari said with a smile, “I have attended several memorial events on Jeju 4·3. I’m glad to see that the discovery of truth and the restoration of honor proceed steadily.”

The organizers initially expected some 250 visitors, but the number of participants surpassed 350 people by the end. The attendees of the memorial event included Koh Hee-bum, chairman of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, and other officials of the foundation, as well as those participants representing the Association of the Bereaved Families of Jeju 4·3 Victims and the Jeju provincial government.

The steering committee members of the Tokyo 4·3 Society, including chairman Cho Dong-hyun, play a big role in the success of the annual memorial event in Tokyo. More than half of the steering committee members are Japanese scholars and experts, who have actively engaged in publicizing Jeju 4·3 in Japanese society.

The ceremony began with the recital of a memorial poem by Kim Soon-ae, a Korean residing in Japan, in order to bring the spirits of the deceased victims into the venue. Kim’s recital of the Japanese poem calmed the memorial hall with the accompaniment of Geomungo.

“Who on earth ordered the killing of Jeju residents? It was a crazy time. Your voices collected from under the sea are ringing in the sky after 74 years have passed. The spirits that could not sleep, the years that they had to wander, the noble hearts that had to be exchanged for lives! May the god of wind on Mt. Halla bring them all to gather here.”

The poem recital was followed by the remarks by Cho Dong-hyun, chairman of the Tokyo 4·3 Society. As always, his speech was simple and concise. Cho stated, “The memorial event, which used to be held every year for more than 20 years, has been resumed after three years due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The leadership of the resistance forces, who rose in the space of liberation against national division and longed for the reunification of Korea, remain excluded from the victims. There also remains a challenging task to put pressure on the United States to make an official apology.” Concluding his remarks, he said, “I am happy that the door to the right path of resolving Jeju 4·3 is now open as the statutory compensation for the victims and exoneration for the wrongfully convicted have become available.

Lecture on the relationship between Jeju 4·3 and post-war Japan given by Prof. Nakano Toshio

Nakano Toshio, a professor emeritus at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies and a steering committee member of the Tokyo 4·3 Society, gave a lecture on “Jeju 4·3 Resistance and Japan’s Post-War History. As he spent two years for the paper, the lecture was highly appraised as an insightful examination of Jeju 4·3 and the post-war issues in Japan. Nakano is an expert in the history of Japanese thought and has studied the “continued colonialism” in post-war Japanese society. He approached Jeju 4·3 by looking into the Japanese colonialism that encompasses the Japanese colonial period, the migration of Jeju people to Japan, the liberation of Korea and the subsequent issues, the 1952 San Francisco Peace Treaty signed during the Korean War, Japan’s postwar reparations, and the Indonesian genocide in the 1960s. His lecture was easy to understand with the analysis of Jeju 4·3 from a new perspective, and received applause from the audience. “We cannot understand Jeju 4·3 if overlooking Japan’s post-war history,” he pointed out. He added: “Considering Jeju 4·3 in Japan is to remember the victims and to demand justice, as well as considering and guaranteeing the dignity of life of Koreans in Japan who are related to Jeju 4·3. It is also to hold Japan accountable for its history of colonialism, to question the ongoing colonialism in Asia, and to realize a fair, decolonized world.” According to his lecture, “Jeju 4·3 was the first massive violence that took place at the turning point of the liberation of Korea toward division and war, and behind it was the invasion of Japan as a modernized colonizing empire, the dissolution of East Asia and reorganization into the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere through the colonial rule by the Great Japanese Empire, and the concurrent fight for hegemony staged by the great powers.

[The event hall is filled with the participants in the memorial ceremony and the concert.]

ROK Ambassador to Japan reminisces on commemorating the 40th anniversary of Jeju 4·3 while studying in Tokyo

Kang Chang-il, ROK Ambassador to Japan, was the first ambassador to attend the Japanese memorial event. The former director and chairman of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute and a third-term lawmaker reminisced his taking the initiative in organizing a memorial event while studying in Japan. Ambassador Kang, who arrived later than planned this year, said he organized a memorial ceremony marking the 40th anniversary of Jeju 4·3 in 1988 while studying in Tokyo, in collaboration with novelist Kim Sok-pom and other like-minded friends. According to Kang, people in Japan were introduced to Jeju 4·3 through novels authored by Kim Sok-pom and Kim Si-jong. “In fact, the movement to discover the truth of Jeju 4·3 and restore honor to the victims began in Japan,” he recalled.

He also appraised the movement as a globally recognized example of liquidating the past as well as a movement for peace and mutual prosperity. “Let us make concerted efforts to create a world where people can live in harmony,” he added.

Singer Park Bo, a second-generation Korean living in Japan, performs “Jeju 4·3”

The second part featured a stage performance by Park Bo, a second-generation Korean-Japanese singer. The audience lapsed into silence when he began to sing “Jeju 4·3,” as if letting out a wailing cry from the rough sea. Park’s other song, “I Really Love It,” reversed the atmosphere, warming the hall with amusement. While the singer sang two songs as an encore, the audience stood up and danced to his music.

Kobayashi Yukie, who was invited to the memorial event by a friend, took a Korean language course at Nishogakusha University two years ago when she encountered Jeju 4·3 through “Jiseul,” a film about the historic event. She said it is her understanding that Jeju 4·3 was a case in which residents were slaughtered due to the government’s three-year crackdown. “I heard that the movement to discover the truth and restore honor to the victims led to many achievements, and there is a need to investigate the damage caused to the Korean residents in Japan,” she stressed.

Kim Sok-pom, a 96-year-old novelist, also briefly attended the after-party. Kim could not make it to the ceremony and concert during the day, but took a taxi to the party late in the evening, despite his difficulties with mobility. Kim shared a pleasant conversation with his old friends, including Ambassador Kang Chang-il and Chairman Koh Hee-bum, and encouraged the event organizers.