From the past toward the future: Intergenerationally transmitted Jeju 4·3 memories and postmemory issues

Kim Minhwan

Professor, Hanshin University

An associate professor at the Peace and Liberal Arts College of Hanshin University, Kim earned his M.A. and Ph.D. in the Department of Sociology at Seoul National University. The title of his doctoral dissertation is “Comparative Research on the Formation of Peace Memorial Park in East Asia – Focusing on the Cases of Okinawa, Taipei and Jeju Islands”. In the thesis, he identified the war and violence that had occurred in East Asia during the dissolution of the Japanese Empire from the perspective of “violence that gave birth to a state”, not from the perspective of “state violence”. Kim co-authored “Besieged Peace, Refracted War Memory: A Study of Kure, the Naval Port of Hiroshima Bay”, “Road to Okinawa”, and “Border Island, Okinawa: Memory and Identity”. He also participated in the compilation of “Rebirth of Cold War Island, Jinmen” and in the translation of “Cold War Island: Quemoy on the Front Line”. During years of research, he released numerous articles, such as “The Geopolitics of East Asian Border Islands and the Structural Causes of State Violence in the Establishment Phases of the Cold War”, “The Paradox of Postwar Japanese Historiography and the History of Okinawa Prefecture: From Nationalized History to Denationalized History”, and “Controlled Movement and Boundary Adjustment: Focused on Films of Imjin River Bridges”.

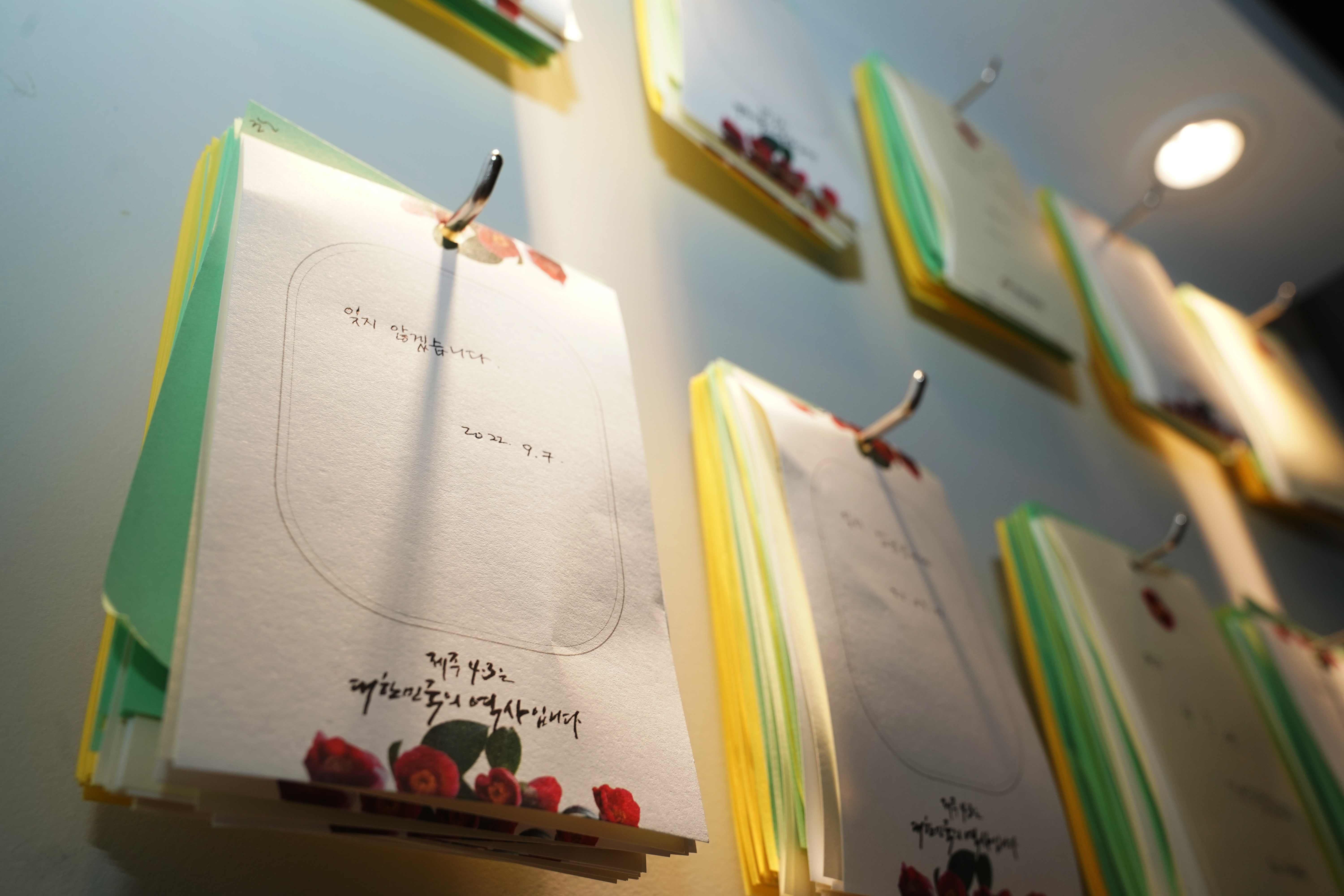

After analyzing the “peace parks” (memorial parks) in Jeju, Okinawa, and Taipei for my doctoral dissertation, I wanted to analyze what occurred to visitors to these parks after touring the sites. Although the stories of those who planned and executed memorial exhibitions and the materials that they left behind formed the core of my doctoral paper, I failed to contain the thoughts of the ordinary audiences, which I considered as the limit of my dissertation. For the so-called “audience analysis”, I have looked through the two-month guestbook messages at the Jeju 4·3 Archives Hall of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park. Unlike my expectation that the substantial amount of the messages would enable a statistical analysis to some extent, I was bewildered as I checked and organized the contents. This is because the messages were mostly filled with the same statement “I will remember.” In particular, there was hardly any exception in the case of the messages left by students. I even wondered if they were told to write the given statement as the right answer when taking a group tour of the Jeju 4·3 Archives Hall.

Having no choice but to give up statistical analysis, I became curious about what the “object” of the sentence was. As the guestbook authors were visitors to the Jeju 4·3 Archives Hall, the statement would naturally be intended to mean “I will remember Jeju 4·3.” However, it clearly lacks specificity, that is, it failed to specify the things, events, people, or periods related to Jeju 4·3. As is well known, Jeju 4·3 features exceptional complexity and multidimensional aspects as it broadly spans Jeju’s chaotic situation after the 1945 national liberation, the protests and firing on March 1, 1947, the subsequent general strike and suppression by the U.S. Army Military Government, the armed uprising on April 3, 1949, the May 10 general election in the previous year, the collision between the armed forces and the counterinsurgency forces, the assassination of Col. Park Jin-kyung, the merciless suppression and massacres committed after the inauguration of the South Korean government, the preliminary arrests and the Korean War, and the lifting of the ban on trespassing Mt. Halla. It would be difficult to remember all the different moments and related figures or to make a quick comment on all of the above. Therefore, it is understandable to simply note “I will remember,” omitting the object of the sentence.

However, specifying the object of “I will remember.” is related to the post-event generations’ search for an opportunity to remember the historical event with a focus on something. It is the process of constituting a framework for interpreting and elucidating the event in their own language; and above all, it is the starting point for the act of “remembering their own selves,” who decided to remember the event. Accordingly, it should be considered serious if the sentence “I will remember” without the object means the absence of the process where the post-event generations relate themselves to the event. This is because it could be another expression that they simply accept Jeju 4·3 as “something to study for a school test and common sense to be aware of”.

It is unclear whether the memo-type sentence and the time constraints resulted in the absence of the details and the simple expression of the author’s determination, or whether the author merely perceived the past event as “common sense” without relating himself or herself to it. The reason could be understood as either of them depending on who wrote the message; but what arouses my curiosity is the ratio of the two. Which would account for a higher rate? And what about the ratio of those students who didn’t even leave the note “I will remember”? Although it would be difficult to find the correct answers to these questions, it would be the most problematic point from the perspective of “postmemory”. “Postmemory” is a concept proposed by Holocaust researcher Marianne Hirsch to refer to the memories of the generation after the Holocaust, distinguishing them from those of the generation who experienced the event firsthand, in dealing with trauma history. According to Hirsch, “postmemory describes the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before — to experiences they ‘remember’ only by means of the stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up.” In other words, postmemory, postmemory is a problem consciousness introduced to deal with secondary memories, the memories of the “generation after”, which are distinguished from the traumatic memories of the preceding generation due to generational and historical distances.

Scholars including Hirsch have conducted research focusing mainly on how postmemory is formed in kinship or other close relationships through media such as family photos. A family member of a Jeju 4·3 victim named Jeong Hyang-shin turned the memorial ceremony into a sea of tears by giving a speech titled “My grandmother doesn’t eat fish”. This is a good example of how postmemory concerning Jeju 4·3 is built and what power it holds in relationships that presuppose family intimacy. In fact, Jeju has a plentiful resource that can serve as materials of postmemory.

[Letters of wishes in the Permanent Exhibition Room of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Memorial Hall]

However, what is more important in relation to postmemory is how to transfer memories and gain empathy in a relationship that does not presuppose intimacy. This issue has become increasingly important concerning not only Jeju 4·3 but also other various historical issues of Korea such as the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement and the April 19 Revolution, where statutory and institutional methods have been employed for the “liquidation of the past”. How on earth can a person remember an event that he or she has not experienced? The issues related to postmemory in a non-intimacy-based relationship continue to form a ‘battleground’. There is a fierce competition in progress for the coming generations’ memory and empathy, and the competition will be even more severe in the future.

In fact, the trend of concern is not limited to Korea. This is because “fake news” or “post-truth” issues are spreading simultaneously around the globe. According to the Oxford Dictionary, “post truth” is a term defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” Those living in the era of post truth receive information first depending on whether or not such news or information is consistent with their worldview, rather than considering the objectivity or reality of the information.

What we have to consider regarding postmemory and post truth issues is that this weapon on the battlefield may not correspond to the “historical truth” itself. Historical events subject to the liquidation of the past have already been officially interpreted in the past by those that held power at the time. Jeju 4·3 was interpreted as a “communist riot,” the civilians killed in the Korean War were as “reds,” and the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement as a “riot” or “situation.” It was extensive data and evidence on the “facts” or “truth” that were employed as weapons to challenge this official interpretation. And based on this, the existing historical interpretation has been corrected. Therefore, the “truth” based on these data and evidence is undeniably critical.

However, those who refuse to acknowledge this “truth” based on data and evidence and attempt to revert to historical interpretations before the liquidation of the past have run a long-term project to dominate the “hegemony” of civil society, and the attempt is still in progress. They believe that the first step in this long-term project is to make their argument equivalent to the new “official” interpretation of history which came to be socially recognized as a result of the liquidation of the past, that is, establishing their argument as a competing one. This tactic seems to have been somewhat successful in some cases including the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement, and may have been more successful than has been ostensibly revealed.

The arguments supported by the evidence they manipulated and fabricated have been repeatedly refuted through the correct evidence, testimony, and authority. However, the effect of the iteration is, ironically, to socially strengthen the competence of their arguments. This is because, be they objective facts or not, the form where arguments and rebuttals are made looks like a controversy itself. This effect helps create an illusion that the historical interpretation agreed upon as a result of the liquidation of the past in the discourse is an “official history” and that claims based on manipulation and fabrication appear to be “alternative history.”

Currently, this is not a marked trend in relation to Jeju 4·3. That does not mean, however, that the trend seen in the Japanese military sexual slavery issue and the May 18 issue will not occur in the case of the Jeju 4·3 issue in the future. How will this environment affect the generations to come, especially after the institutional resolution of Jeju 4·3 is completed based on the Jeju 4·3 Special Act; that is, when Jeju 4·3 is firmly established as an “official history”? I believe that this is what we should deeply ruminate on at this point. Is there any possibility that future generations will happen to feel a sense of duty and oppression concerning the “official history” and feel “liberated” after encountering the so-called “alternative history”? It is as important to have an emotional and affective understanding of this aspect as to organize accurate facts about past events and discover the truth without wavering. Generations who have not experienced Jeju 4·3 and the subsequent process of discovering the truth and exonerating the victims should be able to speak of the historical event in their own words so that they can naturally fight against the “historical negationist” forces. To this end, it is necessary to divert from using language that has been officially “agreed-upon” or “reached through compromise” to enable history to resonate with the current problems of the generations after. As Bae Juyeon puts it, “What is more important is the implication of the ‘present’ memory politics surrounding the ‘past’ and how to build solidarity with those who directly experienced the past and not lapse into party-centeredness.” The task of passing down the memory of Jeju 4·3 to the coming generations is to allow them various opportunities in their daily lives to remember using “their own selves who will remember Jeju 4·3,” not to didactically inform them of the historical truth based on the data and evidence organized by the generations before them. To reiterate, the task strongly features emotional and affective aspects.