Park Kyoung-hun, Executive Director of Jeju 4∙3 Archive Exhibition

Collections held by Jeju 4∙3 Peace Foundation on display for the first time

Since its opening, the Jeju 4∙3 Peace Foundation has striven to collect material related to Jeju 4∙3. The Jeju 4∙3 Archive Exhibition is the first opportunity for the foundation to open its collection to the public. The exhibition mainly contains the foundation’s archives, but collections leased from other institutes have been added, giving the different historical contexts of Jeju 4∙3. With this exhibition, the foundation has brought together into one place a great quantity of Jeju 4∙3-related materials that were previously displayed separately. The items and remains discovered through exhumation are excluded from the exhibit, and instead, the show largely consists of documents, photos, books, video images, and news articles that were produced during Jeju 4∙3 or the process of uncovering the truth of the tragedy. In particular, the exhibition contains much of what the foundation has prepared over the past several years for the inscription of significant documentary heritage on the relevant register of the Memory of the World (Mow) Programme.

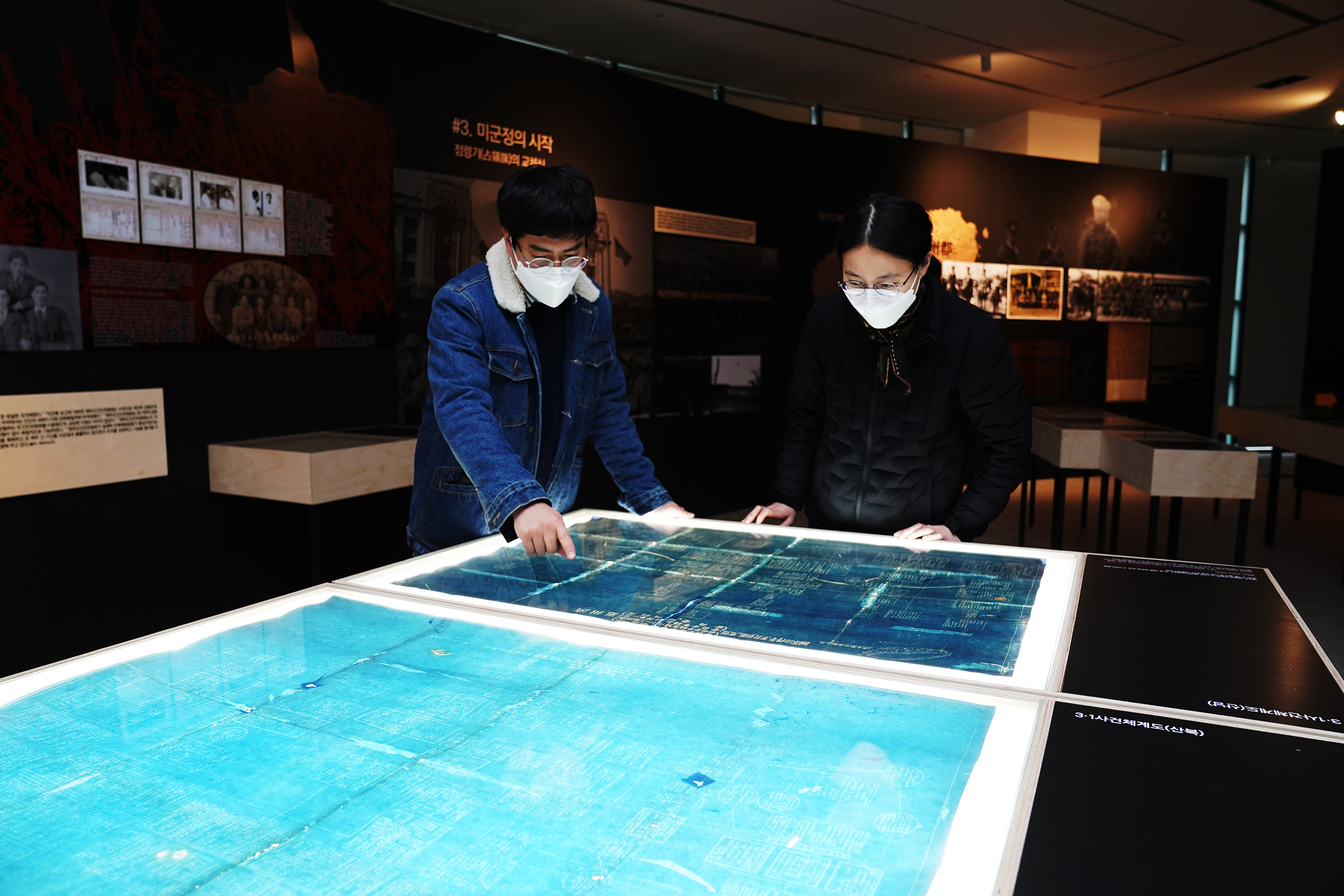

To add more information for visitors, the exhibition is divided into two parts. The items of Part 1 — displayed in Room 1 and 2 — cover the period spanning from 1945 to 1954, while Part 2 contains the materials collected from the 1960s to this day.

The Part 1 exhibit also contains collections leased from the National Archives of Korea and the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History, including: The Declaration of the Alliance for the Korean National Government, which was urgently distributed before and after national liberation day; the Request for Cooperation for the Military Government, which was propagated as a flyer by the United States Army Military Government in Korea; the Promulgation of Martial Law on Jeju Island (Presidential Decree No. 31), which approved the unlawful martial law for the scorched-earth operation and the ensuing massacre; the 12th Cabinet Meeting Minutes – Decisions (Ministry of Home Affairs – on the agenda of dispatching 1,000 police force personnel for special counterinsurgency operations), where president Rhee Syngman ordered the brutal suppression of Jeju residents; the Register of Convicts from the Courts-Martial, which exerted the power of life and death over those wrongfully convicted and imprisoned on the Korean mainland; the 104th Cabinet Meeting Minutes (on the banning of proclaiming the police’s preventive arrests of residents), which permitted police to conduct secret arrests of residents; and the Request for Financing the Promotional Fund for Jeju Island, which contains the first official comment on the loss of human lives and financial assets after the scorched-earth operation ended.

These valuable documents were able to be presented to the public through the exhibition with the support and cooperation of their holders. The materials are valuable in that they represent the inflection points in history that determined the destinies of Jeju residents.

Noticeably, the exhibit displays a real ballot box that was used for the constitutional General Election on May 10, 1948. The Jeju 4∙3 Peace Museum also decided to open to the public other valuable collections, including: The March 1 Statement, which was distributed during the 1947 Jeju-eup People’s Congress commemorating the March 1 Movement; the Outline of Jeju Island’s General Strike, Riot, and Attacks (concerning the Preparatory Committee for the March 1 Commemorative Struggles, the Struggle Committee for the Countermeasures against the March 1 Incident, and the Joint Struggle Committee), which was drawn up by the police during the March 10 General Strike; the Statement of April 10, 1948, which was announced under the name of the 5th Regiment of the Halla Mountain-based People’s Liberation Army; the Written Plea, which the Gujwa-myeon Struggle Committee distributed to the residents of Gujwa-myeon on Jan. 13, 1949; an original copy of the New York Times published on April 25, 1948, which included an article about the outbreak of Jeju 4∙3; and a photo of the exhumed remains of Kim Dal-sam, the former chief commander of the mountain-based armed guerilla forces.

Exhibition Room 1 of Part 1

In addition to the above-mentioned showcase, the walls of the exhibition rooms have been adorned with more photo and newspaper images to allow for a chronological overview of the historical events. Particularly, the enlarged newspaper articles are easy for the visitors to read, while the media reports at the time of Jeju 4∙3 help to better understand this segment of Jeju’s history.

The exhibit of Part 2 is mainly focused on the period after Jeju 4∙3. In particular, it displays The Death of the Crow, a novelization of the story of Jeju 4∙3. The book was published by Kim Sok-pom in Japan in 1957, when Oh Won-gwon, the last armed guerilla, was arrested in Daecheon-dong, an eastern mountain village of Songdang Town, Gujwa District. The novel on display is the first edition of the collection of the writer’s short stories, including The Death of the Crow.

Other items of the Part 2 exhibit include: The first edition of The History of Jeju People’s 4∙3 Armed Struggle published in 1963; the first edition of Sun-i Samch’on; the posthumous work of Kim Ik-ryeol, the 9th Regiment leader of the National Defense Guard; an original copy of The Factual Record of the Tosan-ri Massacre, which the Tosan Village residents developed themselves concerning the massacre of their neighbors by the counterinsurgency forces; an original copy of the Jemin Ilbo with the first issue of “Testimonials about Jeju 4∙3”; literary writings related to the government’s “Red Hunt”, which resulted in the indictment of those who produced it; and a documentary video clip titled “A Wakeful Shout.” Unfortunately, the limited space allows for the display of only a fraction of the enormous amount of materials gathered related to Jeju 4∙3.

The highlight of the exhibit is the bank of transparent acrylic towers displayed on the exhibition hall. Each tower contains a stack of the copies of the Request for Deliberation and Identification of the Jeju 4∙3 Victims and Victims’ Families, which was submitted to the Committee on Discovering the Truth of Jeju 4∙3 and Restoring Honor to the Victims. The requests, which were written on 2-3 mm-thick A4 page, are the collection of the “deaths,” a record of the sacrifice of individual Jeju 4∙3 victims. The stack of more than 14,000 pages is the most significant material ever collected documenting the victims of Jeju 4∙3.

The Jeju 4∙3 Archive Exhibition also features some of the rarest historic materials, such as documents created immediately after national independence and during the establishment of the Korean government. In particular, a substantial amount of those materials that shaped the turning points of contemporary Korean history are being shown as they were during national liberation and the ensuing Jeju 4∙3 tragedy. The items on display also include some other valuable materials that the Jeju 4∙3 Peace Foundation decided to open to the public for the first time. Visitors to the exhibition will find it even more interesting to enjoy viewing historic materials that are normally difficult to access.

Historical items speak for themselves

The core of the Jeju 4∙3 Archive Exhibition is that the items on display are the main character of the show. The most optimized method of producing the exhibition is to let the historical items speak for themselves. The event is unique in that this method has been applied to its planning. Although the exhibition shows its limits in the final settings, the original intention was to let the items speak for themselves.

The format of an exhibition often leads to the showcase of items segmented by specific themes. However, this method does not make it easy for visitors to view genuine historical content. Inevitably, the Jeju 4∙3 Archive Exhibition adopted this format for some items, but great effort was put into ensuring the content of the exhibition comes from the time of Jeju 4∙3. For instance, the Permanent Exhibition of the Jeju 4∙3 Peace Memorial Hall simply shows the historical material as evidence of the past, while the latest exhibition accounts for the items on separately printed panels to allow for the understanding of the past events in more detail. This way, the visitors can access news articles and other material produced at the time of Jeju 4∙3.

Exhibition room of Part 2 (left and right)

Jeju 4∙3 materials, exceptionally rare

Every time I visit memorial halls in Europe or other regions, I used to feel envious of the vast amount of historical material on display. Going through World I and II, the European society left an enormous visual record, such as documents and photographs. Most of the memorial halls for the Holocaust contain a colossal amount of items on display. In contrast, historical materials related to Jeju 4∙3 are exceptionally rare. This would be due to the difference in the cultural capability of creating visual records, and to the fact that Korea was one of the poorest countries, which had just broken away from colonization. Moreover, it should not be overlooked that many of the materials related to Jeju 4∙3 were covertly and/or purposefully “lost” because the event was a relatively low-intensity conflict.

For the scorched-earth operation on Jeju Island, the United States Army Military Government in Korea and the Rhee Syngman administration put Jeju Island into a completely isolated situation. They blocked the island’s air and sea routes by flying L-5 liaison jets and dispatching destroyers to the Jeju Strait. Everything was controlled by the Korea Military Advisory Group. Under these circumstances, most of the documents or photographs containing the truth of Jeju 4∙3 were lost or hidden. In the course of Jeju 4∙3, however, the leading forces of resistance also failed to leave ample documentary heritage. Not just the leading forces, but also the victims’ families had to erase any remaining trace of Jeju 4∙3 so as not to be branded as being “red.” Many survivors often recall in their testimonials that they had no choice but to burn even their last remaining photograph of their deceased family members. Thus, be it documents or photographs, only those that had supported the narrative of the so-called victors remained until this day. Most of the Jeju 4∙3-related materials were destined to fail to exist because both the perpetrators of the massacres and the victims and their families had to burn even the last remaining piece of evidence to ash, the former trying to conceal their crime and the latter trying to avoid the false accusation of being communists.

Nevertheless, the Jeju 4∙3 Peace Foundation has collected everything it could find related to Jeju 4∙3, just like a farmer gathers even the empty heads of grain in the field after the fall harvest. Although it may look insufficient, some of the items bear significance and add value to the foundation’s archive. None of the materials now on display were easily earned. The process of obtaining them was the outcome of a gruesome fate. Some of the documents even determined the life and death of Jeju residents. I expect the Jeju 4∙3 Archive Exhibition will weave the scattered photographs and documents together by a common thread, and to share their value as evidence of the truth of Jeju 4∙3.