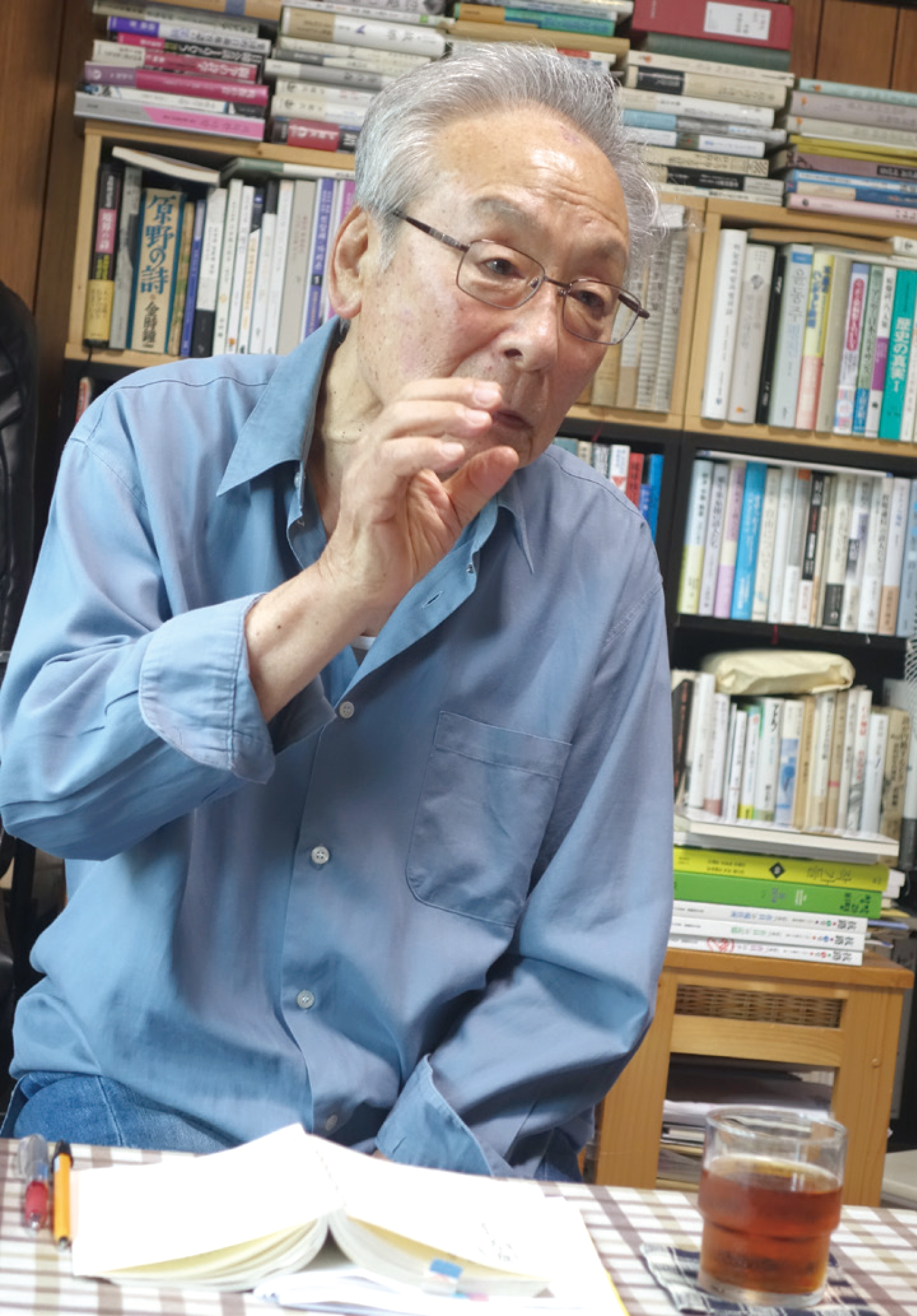

Poet Kim Si-jong, a pioneer of Jeju 4‧3 literature

Editor’s note:

A young man who left Jeju Island in his 20s seven decades ago commemorated the 70th anniversary of Jeju 4·3 in Japan. Poet Kim Si-jong currently lives as a Korean national in Japan, keeping the memories of his home and parents alive in his heart. For Kim, the fact that 70 years have passed since Jeju 4·3 is equal to the fact that 70 years have passed since he began living as a Korean resident in Japan. In the last70 years, the poet has become a leading figure in the Korean-Japanese literary circles and has received renowned awards such as the Takami Jun Prize and the Osaragi Jiro Prize. In commemorating the 70th anniversary of Jeju 4·3, I wondered about contemporary events, literary works, and of the poet, who once said, “The deceased Jeju 4·3 victims will still live unless our memories fade away, unless we neglect them.” On a late autumn day, I interviewed the elderly poet at his residence in Osaka, Japan.

Interview by Heo Young-sun, director of Jeju 4·3 Research Institute and poet / Photograph and arrangement by Cho Jung-hee, researcher of the Research Department, Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation

Profile: Kim Si-jong

Born 1929 in Busan, Kim Si-jong grew up in Jeju. After participating in the Jeju 4·3 resistance, Kim stowed away on a ship to Japan and has since devoted himself to the Korean nationalist movement and poetry as a Korean national residing in Japan. Kim was allowed to visit Jeju for the first time after an absence of more than 50 years in 1998 when the Kim Dae-jung administration announced a special policy concerning Korean leftist activists in Japan. The poet acquired Korean citizenship in 2003 with his original domicile registered on Jeju Island. In 2018, his collection of poems Horizon was first published in Korean. A renowned Japanese publishing company named Fujiwara Shoten started in January of 2018 and published A Collection of Kim Si-jong’s Poems (in 12 volumes).theater. Kim authored several poetry collections, such as Horizon (1955), Epic Poems in Niigata (1970), Poems in Ikaino (1978), A Book of Poems on Gwangju (1983), Poems of Wilderness (1991), Poems of a Periphery (2005), and The Lost Season (2010). His other publications include a literary review collection From a Crevice of the Life of “Zainichi Koreans” (1986), a collection of interviews Why I Continued to Write, Why I Remained Silent (2001), and a memoire Living in Joseon and Japan (2016). In 1986, From a Crevice of the Life of “Zainichi Koreans” received the 40th Mainich Publishing Culture Award. In 1992, Poems of Wilderness was selected as the special prize winner of the 25th Oguma Hideo Prize. In 2011, The Lost Season won the 41st Takami Jun Prize, making the poet the first Korean-Japanese winner of the prize. Kim was also the first poet to receive the Osaragi Jiro Prize in 2015 for Living in Joseon and Japan.

Q) Today’s special interview will be released in Jeju 4·3 and Peace, the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation gazette. This year marks the 70th anniversary of Jeju 4·3. What would the 70 years mean to you, Mr. Kim?

A) Never have I attended an official memorial event for the Jeju 4·3 victims held in Jeju, not even once. That is a burden for me. Still, I have courteously put my hands together in prayer for April 3 here in Japan. Should I consider my absence my destiny? April 3 happens to be when I perform the ancestral rite for my mother. What a coincidence that my mother passed away on the same date. Every year, it reminds me of what I have always determined to forget. Even now, I often see it in my dreams, the four days I stayed in Jeju’s Gwantal Islet in hiding. How agonizing and dreadful it is to dream of those days. It is such a nightmare. This is why Jeju 4·3 cannot be a past event for me, even after 70 years have passed. Living as a Korean national in Japan, I still have to embrace and bear the burdensome memory of Jeju 4·3.

Q) You mentioned that Jeju 4·3 cannot be a past event. How would you define Jeju 4·3?

Q) You mentioned that Jeju 4·3 cannot be a past event. How would you define Jeju 4·3?

A) It was in June of 1949 when I escaped from Jeju Island. At the time, people on Jeju called Jeju 4·3 a people’s uprising. And as a nickname befitting the people’s uprising, the local South Korean Labor Party bloc (the leadership of the resistance) was referred to as Sanbudae [a mountain-based corps]. Sanbudae was a very affectionate nickname. However, that term of endearment disappeared when the constabulary forces were dispatched from Mokpo, Chuncheong, and other regions on the Korean mainland to support the counterinsurgency operations. Although the nickname “Sanbudae” was replaced with “communist rioters” due to the counterinsurgency operations, it was certainly legitimate to start the 4·3 uprising. We had a very pure passion for justice, thinking, ‘Now is the time that righteousness and justice begin!’ I admit that there occurred substantial conflicts and problems when the uprising was nearing its end. However, it is an evident fact that within a larger framework, the uprising pursued national unification of Korea for the purpose of establishing a unified government. In a nutshell, I would define Jeju 4·3 as an explosive realization of justice.

Jeju 4·3 gave me strength to endure the life of a Korean resident in Japan

Q) The 70th anniversary of Jeju 4·3 means the 70th anniversary of your life as a Korean resident in Japan.

A) I have lived most of my life in Japan, as a Korean national. My Korean life in Japan is full of continuous hardships that no others would have experienced. The financial difficulties of a Korean national in Japan were a relatively insignificant problem. When my poems and reviews released in the literary coterie magazine Azalea confronted political criticisms from the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chongryon), I began to be degraded as a subject for the systematic criticism and suppression by Chongryon. It felt like I was being treated as a subhuman being. But I refused to give up my determination to write poems and continued my struggle against the organization, while I was condemned for being a nihilistic nationalist and an anti-organizational reactionary and was suppressed for my doctrinaire ideology. I could endure it all not because I was a particularly courageous man but because I am one of those who experienced Jeju 4·3. I survived the life of a Korean-Japanese life based on my experience of Jeju 4·3. Likewise, I believe that the absence of those who are associated with Jeju 4·3 would turn the record of the Korean expatriates in Japan into that of the people without a guiding light. When learning about a family member who died due to Jeju 4·3, even the younger Korean-Japanese generations who know nothing about their homeland or grandparents realize that their identity is rooted in Jeju. These days, students who had no knowledge of Jeju 4·3 have great interest in what happened. The Jeju 4·3 movement has continued in Osaka because the younger generations perceive that they inherited their ancestors’ capacity and spirit of resistance. Even without self-awareness, the stream of that consciousness has continued.

Q) Now, let’s talk about your literary works. Not just in Poems in Ikaino, but also in Horizon whose Korean translation was recently published, you didn’t directly discuss Jeju 4·3, despite the related fragmentary images.

A) As a person who suffered Jeju 4·3 firsthand, I was unable to speak of my personal experience for a long time. The first reason for my silence is that out of fear for the possible defamation of legitimacy of the people’s uprising due to my existence, I could not dare confess that I had experienced Jeju 4·3. The second reason is my sheer cowardice. Mentioning that I moved to Japan because of my Jeju 4·3 experience would reveal that I attempted an unlawful entry into Japan, which means that I would be forced to return to Korea. Regrettably, I could not speak of my experience to protect myself. As if cramming my fear and bottomless remorse deep into my heart to whelm my memory over, I wrote my literary works in the Japanese language. However, the 70th anniversary of Jeju 4·3 gave me the impetus to create a work of drama that could express the philosophy of contemplation through Jeju 4·3. I would like the work to not describe the life of others but how my Jeju 4·3 experience allowed me an opportunity for contrition. Hopefully, it will allow me to thoroughly dig myself out, revealing all of the shameful aspects of my life.

Jeju 4·3 must be reproduced through a heartfelt prayer

Q) Listening to your description of your agony related to your works, I could feel your remorse and introspection about Jeju 4·3.

A) Too often, without deep consideration, we use the term “Jeju 4·3 victims.” This expression arouses a sense of nobleness concerning their deaths. However, the reality of the deaths due to Jeju 4·3 is that people had to suffer a forced death alongside the most terrifying horror that could immediately freeze their hearts. I should probably call it an infinite numbness of those who couldn’t even close their eyes due to the unexpected end of life. We must not forget the abandoned bodies, the neglected deaths. Thus, we must put our hands together in prayer. Our prayers for the Jeju 4·3 victims must create an “affect” by reproducing the inexplicable horror and numbness of those who were forced to die. The tragedy must be reproduced with the reminiscence through the “affect,” thus lasting through the reproduction process. Only with the prayer performed as I described, will we be able to hand down the genuine aspects of Jeju 4·3 to the coming generations. The current noble, somewhat transparent prayer means nothing more than a formal prayer.

Q) Could you describe in more detail how we can hand down the genuine aspects of Jeju 4·3 to the coming generations?

A) What would happen if one inherits the lessons of Jeju 4·3 with his or her willpower but without learning its true content? Jeju 4·3 is not a special tragedy or atrocity that only belongs to the Jeju people. It occurred in relation to the United States after World War Ⅱ ended. This is the fact that must not be misinterpreted. Jeju 4·3 is one of the tragedies that involved all Koreans. From a global perspective, there exist millions of other victims who share the same suffering. We should understand how America’s anti-communist strategies were designed and what dynamics formed those strategies. This will clearly reveal that the deaths and tragedy during Jeju 4·3 was a part of a victimization caused by this global strategy. I believe that only after this revelation can the local South Korean Labor Party bloc (the leadership of resistance) be more properly recognized.

Although all novels are written, poetry exists without a text

Q) Recently, many people study the significance of Jeju 4·3 in world history. Do you have any advice for them?

A) There is a book titled Japan Diary published by journalist Mark Gayn a long time ago. The reporting of Korea from the book was translated into the Korean publication titled Liberation and the United States Army Military Government in Korea. These are the books that help us understand the significance of Jeju 4·3 in world history and outline the perspective that shaped America’s global strategies. Kim Sok-pom’s well-known Volcano Island would also be helpful. But I think your book To You Who Ask about Jeju 4·3 would be the most persuasive work as it described the atrocity of Jeju 4·3.

Q) Although you describe your poems to be “your revenge on the Japanese language,” your works are full of unrefined Japanese words and have attracted so many Japanese readers. What would be the work that you most care for?

A) I was liberated from the yoke of colonial rule 73 years ago, but it didn’t separate me from the Japanese language, which underlines my consciousness. Rather, I live the life of a Korean resident in Japan who has no choice but to rely on the Japanese language. In the process, I turned my back against the sophisticated and elaborate Japanese expressions, but have used unrefined and unlubricated words to create poems for nearly 70 years. This is my attempt to be liberated from the Japanese language and to take revenge on it. All of my works were published after so many difficulties, so they all are special to me. But considering their quality, I think A Book of Poems on Gwangju is my best. The Japanese literary circles appraised Poems in Ikaino the most, while Living in Joseon and Japan is in its seventh publishing run, selling more than 90,000 copies. I heard that teachers steadily give lectures on my works at major Japanese colleges, which is a very fortunate outcome for me as a poet. But I don’t consider writing poems as my career or my aptitude. Everyone has their own poems, and a poet is just someone who happens to express them with words.

Q) “Everyone has their own poems”

A) Although all novels are written, poetry exists without a text. People all have their respective poems in their hearts. Poems exist in how an individual human being lives his or her own life. Humans have sensitivity that helps commune with everything around them, and poems are created from that sensitivity. A poem is not written by a poet, but writing a poem makes a person a poet.

My spring is always reddish

where a flower is colored and blossoms from within.

A pistil visited by no butterfly attracts flying wasps,

which buzz in April that sprouts like measles.

(…)

Flashing before me are

the pathway, the corner, and the pit

where my loved one dripped with blood.

I, once in there and now overly aged,

live a twisted life in Japan

with the same forsythia and apricot blossoms.

Bright is the sunlight

when April returns with the colorful horizon.

Oh, trees!

You tune into the sound of your own shivering.

Spring revives,

splashing as much remorse as mine.

Excerpted from “Oh, April, the Days Far and Away”