This chapter highlights some of the coverage of the Jeju 4·3 Uprising and Massacre in the island’s first, and still only, English-language news magazine, The Jeju Weekly. When the publication began in 2009, few English speakers outside of academia had heard of Jeju’s tragic history. The paper sought to change that by offering comprehensive articles detailing the tragedy and how it continued to shape the island. Many of The Jeju Weekly’s freelance contributors were English teachers who, like the publication’s readers, were learning about Jeju’s tragic history for the first time. This brought a fresh look to their coverage which allowed them to interpret the events from a non-Korean perspective. The Jeju Weekly also aimed to provide a more accurate picture of Jeju Island than the heavily curated wonderland being sold worldwide by the provincial government of the tourism-dependent island.

Many of the stories here — and throughout this book — come from The Jeju Weekly’s massacre series that ran in 2011 and 2012 to increase understanding of the massacre for an international audience. While most of the information in The Jeju Weekly had been printed in the Korean press a decade earlier, it was news in English and it brought the massacre to the attention of many people for the first time. The mission of the paper to clarify some of the main debates about the massacre such as the controversy over its official title as well as the nature of the American role is clear in the materials selected for inclusion here. The articles included take the form of snippets that encapsulate a key aspect of the story. The headlines and subheadings have been edited to provide the additional details relevant for this new format. All of the stories were available in full at the time of going to print at www.jejuweekly.com.

Massacre defined by political divide

Conservatives prefer revolt, liberals uprising and the government chose incident, but none of these names properly define 4·3

• • •

Jang Jung Eon, director of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, the government-sanctioned body responsible for the information in the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park museum, said, “The right wing wants to define it as a ‘riot,’ and those involved in social movements want to call 4·3 an ‘uprising.’ However, according to the government, the term is Jeju 4·3 Incident. Other terms will cause controversy.”

This is the neutral perspective, chosen specifically to appease both sides of the argument.

Yang Jo Hoon, lead April 3 Massacre investigative reporter for Jeju Sinmun and then Jemin Ilbo from 1988 to 1999, said, “The 4·3 rebellion was political, but the massacre was not. The terminology was very difficult. 4·3 has two facets; one is resistance and the other is the massacre. It is hard to find a single word to combine those two aspects. I’m still looking for the right word…”

• • •

Published under the headline “Massacre defined by political divide” in April 2011.

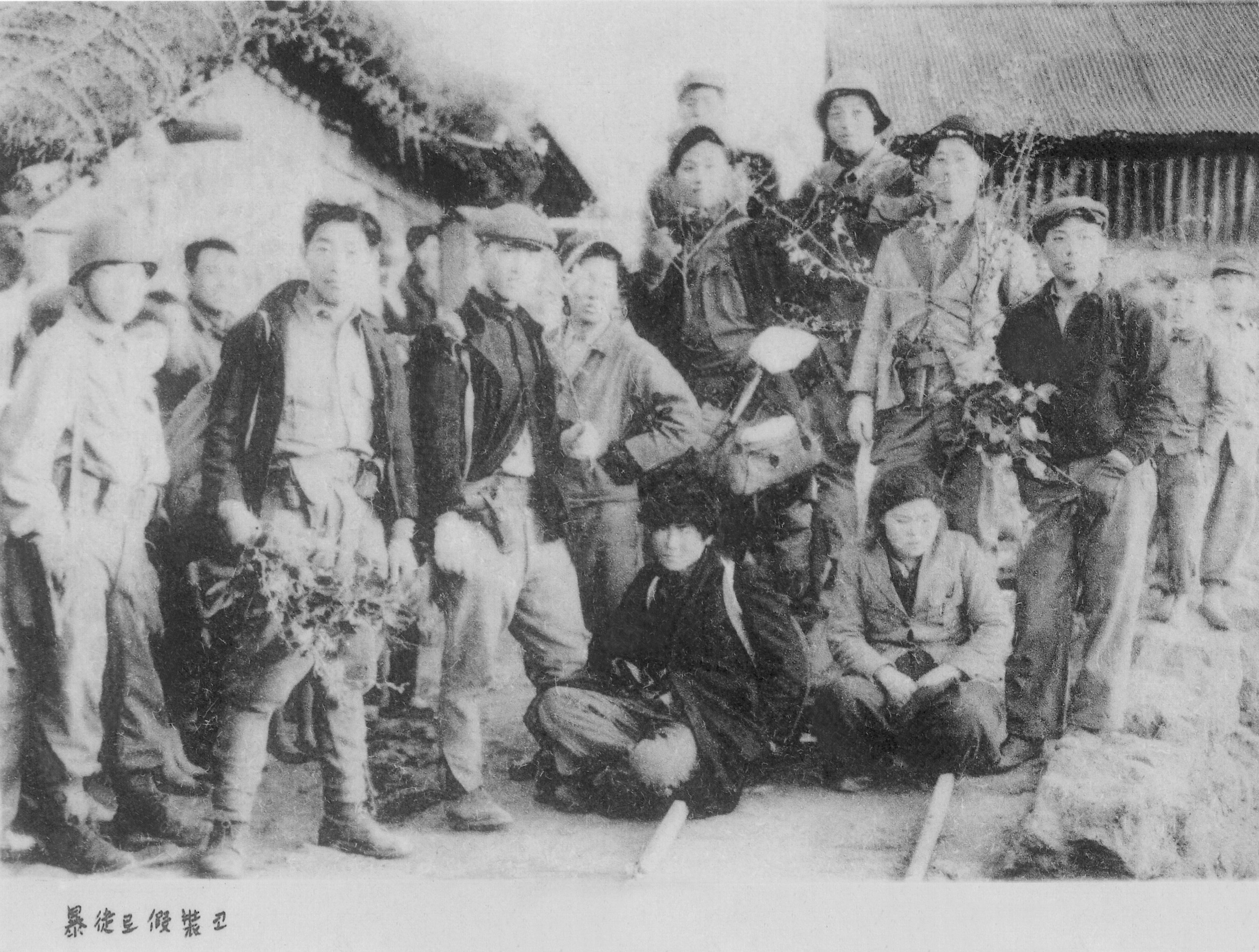

Northwest Youth Association carried out state violence

North Korean refugees driven by the desire for vengeance against leftists formed a formidable paramilitary group

• • •

In a paper presented at the 50th Anniversary Conference of the Jeju 4·3 Uprising and Massacre, Professor Bruce Cumings of the University of Chicago states that at the time, Jeju’s local government and police were comprised mostly of mainlanders who “worked together with ultra-rightist party terrorists,” otherwise known as the Northwest Youth Association.

According to Cumings, they were brutal towards the islanders, exercising more police power than the police. This resulted in Jeju citizens having a deep resentment towards the Northwest Youth Association. What had begun as a group of patriotic anti-communist civilians, quickly became a means to crush anyone who opposed President Rhee and the KDP.

• • •

Published under the headline “The Northwest Youth League” in April 2011.

Jemin Ilbo uncovers truth and transforms public understanding of 4·3

Facing public concern and government opposition, local reporters wrote 500 articles on the uprising and massacre in 1988

• • •

While the Jemin Ilbo was transforming the public’s view of the massacre, those who suffered at the hands of “guerrillas,” those for whom the former image of the massacre reflected their pain, were upset that the perpetrators of their suffering were being cast in a new light. “[They] thought 4·3 was the rebels’ fault, while our investigation team proved that it was wrong. They showed dissatisfaction with our reports … In addition, the police and the military also showed dissatisfaction because they also considered the incident a communist revolt. At that time, it was really serious.”

“I told my journalists that we should not have prejudice. Our job was to reveal the facts about 4·3. Then 4·3 will gradually be evaluated in a right way. What I emphasized was that we should not hurry, but we rather should take sufficient amount of time in revealing the facts, like a marathon runner,” said Yang¹.

• • •

Published under the headline “Seeking the truth” in April 2011.

1 Yang Jo Hoon, current chairman of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, was head investigative reporter for the Jemin Ilbo from 1988-1999.

Thousands remain missing decades after the massacre

As witnesses die, the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation is in a race against time to fill the gaps in its 2003 report

• • •

The new research project, which will take three years to complete at a cost of 200 million won annually, picks up where the other one left off. Its purpose is threefold: to uncover the truth of what happened to 5,000 people (assumed dead) who went missing during the massacre and have yet to be accounted for, to determine which villages victims of the massacre were from, and to understand the aftereffects of the massacre upon Jeju citizens who lived through the tragedy.

“All three aspects we had a hard time finding the truth last time because we heavily relied upon government documents and records,” said Park Chan Sik, Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation researcher and one of seven researchers working on the new project.

• • •

Published under the headline “ ‘Last official research’ on Jeju Massacre victims begins” in April 2012.

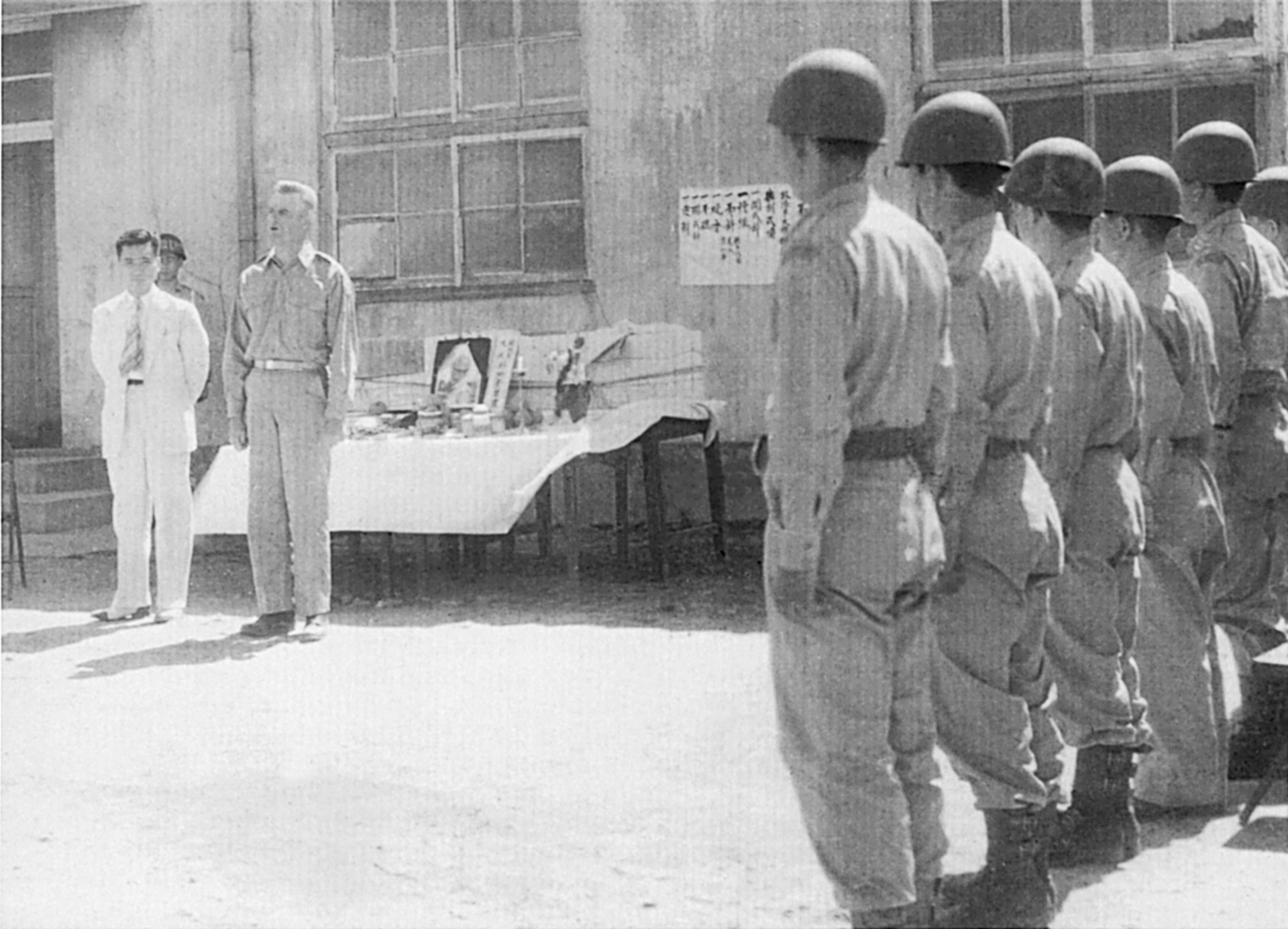

Scorched earth policy responsible for ‘70 percent of the total killings’ during 4·3

Republic’s strategy was a perfect storm of oppressive military tactics

• • •

Lee Mu Kyung, who was 11 at the time, fled with his mother and sister from Ora village to near what is now Gu-Jeju; then when scorched earth began they were evacuated again to the coast near Yongduam. “We were lucky,” he said, and explained that his family was only treated so well by the police because there were none among them who could be a threat. The family of another survivor — Yang Nam Ho, who was 5-years-old — ran instead to the mountains. Both men agree: it was a very confusing time.

Those on the wrong side of the scorched earth line that ran 2.5 miles inland around the perimeter of the island often hid in the caves that dot Jeju’s geography and were generally killed upon discovery. Smoking survivors out into gunfire was “very common” according to Oh, but three children and eight others hiding in Darangshi cave were actually suffocated with smoke. The cave was only discovered in 1992, and research done by Jemin Ilbo, a Jeju newspaper, concluded that the fire had been set by the military.

• • •

He went on to emphasize, “…it is of paramount importance… that all orders pertaining to operational control of the Constabulary [Republic of Korea] be cleared with the appropriate American Advisor, prior to publication.” This would suggest the Republic’s military planned and conducted their own operations, but never without the explicit go-ahead of United States. This includes all scorched earth operations. In a future column to be published in the Jemin Ilbo by Yang Jo Hoon, a U.S. report says, “the 9th regiment has adopted the program of mass slaughter,” and evaluates it as a “successful action.” Another document from PMAG chief William L. Roberts praises the 9th regiment’s commander Song You Chan as displaying “excellent powers of command.”

The scorched earth program implemented on Jeju was, in many ways, a perfect storm of oppressive military tactics: a president eager to exert his new-found powers (even inventing new powers for himself); a hard-line paramilitary organization backed by the fledgling government; a war brewing between and around the two new nations; a people fed up with years of occupation (the April 3 Peace Foundation estimates of violent Jeju citizens range from 350-500 or between 1.2 and 1.6 percent of those killed); and a superpower which allowed and sometimes encouraged the most brutal of tactics.

Published under the headline “The deadly effectiveness of the republic’s 4.3 scorched earth policy” in April 2012.

Bukchon-ri massacre continues to haunt survivors

Chairman of the Bukchon Village 4·3 Victims and Bereaved Families Association recounts the day 300 villagers were killed in cold blood by state forces

• • •

It was a warm late-spring day and I¹ was in the fourth grade of elementary school. I lived in Naensibillebatt, near Bukchon Village, Jocheon-up. As soon as I arrived home, my mother told me to take lunch to my eldest brother who was plowing a field. The lunch was just a clear soup with flour dumplings, sujebi, and some pickled garlic.

• • •

I couldn’t find my brother, but I saw an older man and he took the lunch. My stomach began growling with hunger. I noticed some round yellow pieces of iron scattered about and I asked the old man what they were. He told me they were spent bullet cartridges. “When you grow up I will tell you all about the history of this field,” he said with a sigh, and looked up at the sky.

I remembered a candy vendor ex-changing the cartridges for notebooks and so I started to pick them up. I couldn’t hold all of them, so I filled my hat and glanced at the lunch bag, which contained some leftover soup and dumplings. “Can I eat it, uncle?” I asked. “Sure, I left it for you,” he replied. I will never forget that taste. With the empty bag I combed the field and found about 20 spent cartridges and even rubber shoes and sneakers.

Unwitting, I happily continued to collect the spent cartridges in the field, not knowing they were the evidence of a mass execution which had occurred during the Jeju 4·3 period.

• • •

Published under the headline “Lunch, a rocky field and some spent cartridges” in April 2014.

1 Lee Jaehu was chairman of the Bukchon Village 4·3 Victims and Bereaved Families Association when he recounted this story in 2014.

Is the US responsible for the Jeju Massacre?

Foreign scholars should do more to shine a light on the US’s role, says Prof. Katsiaficas

• • •

“The massacre could only have been carried out with the active knowledge and collaboration of the U.S. military, who maintained direct control over military operations south of the 38th parallel,” Katsiaficas said. “Even after control had been officially relinquished, U.S. control was the reality on the ground.”

Katsiaficas believes that the Jeju Uprising should be seen as part of wider U.S. strategic aims to consolidate power in the region and to build military bases against perceived threats from Russia and China. Comparisons with similar events in Taiwan are elucidating.

“To seize Taiwan in 1947, U.S. forces aided in the slaughter of 20,000 indigenous Taiwanese, whose bodies were thrown to the sea or left to rot in the fields. U.S. policy-makers applied the lessons learnt to Jeju Island,” Katsiaficas said.

The scholar is adamant that had the U.S. public been aware of such mass slaughter, there would have been a heavy political price to pay.

• • •

Published under the headline “U.S. complicit in Massacre?” in March 2010.