The days of Jeju 4·3 never end!

Oh Young-jong (born in 1929 in Hannam, Namwon)

In February 2023, national compensation for Jeju 4·3 victims, retrials for prisoners, and the criminal indemnity project (granted as a compensation to those who were falsely charged and imprisoned under criminal law) created an atmosphere of hope for the just and complete resolution of Jeju 4·3. However, absurd remarks from various political circles and extreme right-wing conservative groups spread over the island of Jeju, stating “Jeju 4·3 was a communist riot” instigated by North Korea’s former leader Kim-Il-sung. It has already been six months without any apology or remorse, and Mr. Oh Young-jong, a 95-year-old man, stands before the court for retrial.

“I am no judge, but I wish I could punish them until they beg for mercy for their wrongdoing.”

Some things cannot be resolved with money, and some things left unresolved because they are difficult to handle come back to haunt those unwilling to address them. Can we resolve Jeju 4·3 without apologies from the perpetrators? This interview concerns Mr. Oh Young-jong, who is seeking damages from Tae Yong-ho, a North Korean refugee and a National Assembly member who is accused of distorting Jeju 4·3.

- by the editor

Interviewed and photographed by Cho Jung-hee

Head of the General Affairs Team, Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation

Are we returning to that communist issue again?

I doubted my eyes when I first saw on the news that “Jeju 4·3 was instigated by Kim Il-sung.” Are we returning to the communist issue after all this time? Then why were we judged not guilty? Why did they compensate us? I was so upset and could not sleep. Is that something a member of the National Assembly should say on TV? And it was a downright lie! What if people believe what he said? He is in such an important position. He should tell the truth.

“Tae Yong-ho is lying! He is falsifying Jeju 4·3!”

So, I decided to bring the issue to the court. I might not be as educated as a National Assembly member, but I experienced Jeju 4·3 myself! My home was burned down in a day. I fled to the mountains in the winter. I was almost shot dead because I was framed as a rioter. I was imprisoned and transferred around Korea, circling Daegu, Busan, Masan, and Mapo for no reason. Finally, there was the Korean War, which I survived, but when I returned home, my parents were long gone. There was not a moment for me to blame anyone because my every move was constantly being watched, which made me feel like I was in a prison without bars. So, after all that has happened to me since Jeju 4·3, I know the truth and lies. Some say they know about Jeju 4·3. Do they know even a fraction of what I experienced? No, it was something you will never understand unless you were there! So, if I see that guy, Tae Yong-ho, I would want to ask him this question.

“Was it Kim Il-sung who laid orders to burn my house, kill my father, and imprison me? When did Kim Il-sung order such things? Clarify the orders!”

Oh Young-jong in his 20s (Back row, far right).

The start of Jeju 4·3

I was 20 years old with little knowledge because I had grown up farming. It is said that people were shot dead by the police at Gwandeokjeong, and that triggered Jeju 4·3. However, in my village, Hannam-ri, no one knew what was going on. There was no one telling that story. There was no one telling us what to do or not do. But I thought something was amiss, and it was because of the Northwest Youth League whose members suddenly stormed our village’s Hyangsa shrine. They were fierce, thrashing about and shooting guns. After that, we avoided going near the shrine. As I recall, that was the beginning of Jeju 4·3.

Even though I was a dumb farmer who knew little aside from growing barley and sweet potatoes, I could understand the northern dialect. I knew they were members of the Northwest Youth League. Why did they come for us? I did not know. We were just victims. They attacked, and we were beaten. They destroyed our belongings, and we could not say a word. They ordered us to bring them chicken meat and drinks. Oh, they were the kings who feared nothing. Why would they come to Jeju, especially all the way down to this rural village, Hannam-ri, to torment us? According to Tae, it was because Kim Il-sung of North Korea had ordered the Northwest Youth League to kill the people of Jeju.

The date was Nov. 7, 1948.

We called both the police and military as counterinsurgency forces. We had to flee even during fieldwork when we saw them coming up from Namwon. We erected bamboo stems on a hill that young people like me would knock down to signal to others that they were coming.

I often stood watch on the hills. There were about three places where I stood guard, including Bokbyeong Dongsan. I did my job well in alerting people to escape. No one died on my watch. Nothing unusual happened during the May 10 general election, too.

The election was conducted at the shrine. I had no ballot, so I stood watch at the shrine instead. I can still remember the police took the ballot box using a carrier after voting was over. At the time, the box was wooden. It all happened on Nov. 7, 1948. As if burning down the whole village was not enough, the counterinsurgency forces arrested every person they saw. Houses were burning, and the gunfire was rampant. Everyone had to run for their life to the mountains. As I came to my senses, the counterinsurgency forces had taken my father, and my mother had gone to Namwon-ri with my younger siblings.

My father was eventually shot dead in Taeheung-ri, along with some other village folk. My mother, who had gone to her family with my two younger siblings, fell ill and passed away. That was one year before I was released from prison. She fell sick because of the desperate situation. She lost her home and husband, and her eldest son, me, was nowhere to be found. With two young children, she had no one to depend on. How dire would that have been for her! Maybe I could have prevented my father from being killed had I not ran away to save my own life. With my father alive, my mother would not have passed away so early. No one knows.

I feel like the deaths of my parents are on me. I cannot bear to talk about my parents without feeling strong resentment. It chokes me. Nov. 7, 1948, is a day I regret, as it haunts me.

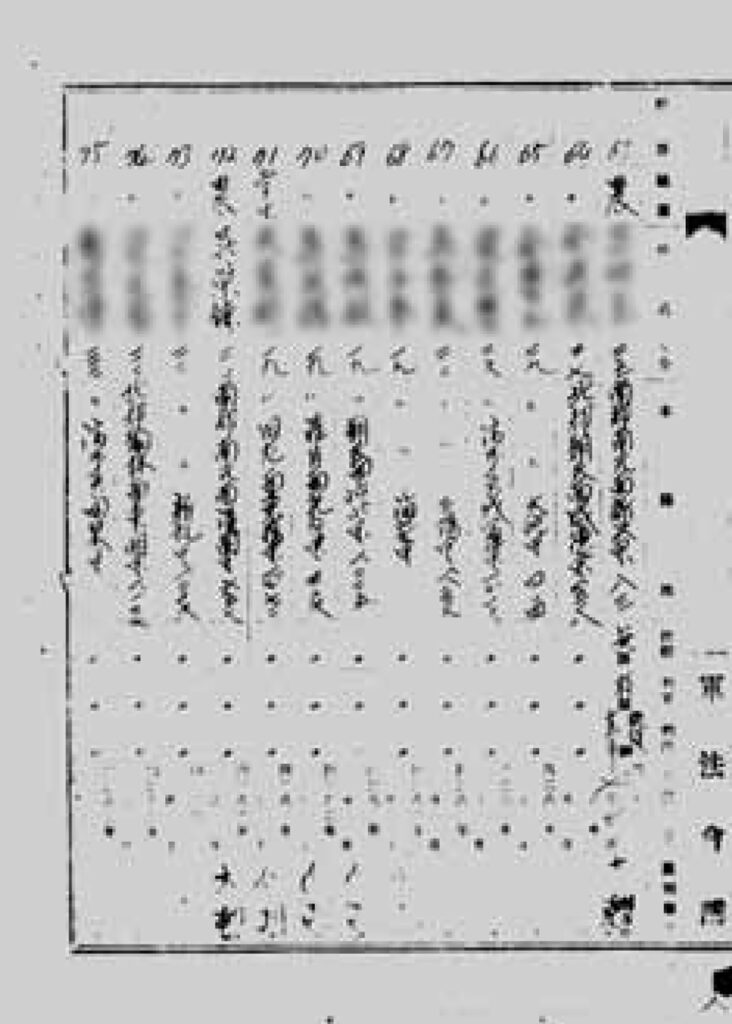

List of convicts in 1949 court martial at Jeju District Prosecutor’s Office

Verdict on Oh Young-jong tried by court-martial, sentenced to 15 years in Daegu Prison, July 3, 1949.

Being shot by the counterinsurgency forces

I spent much time in the forests of Saryeoni as a runaway. The counterinsurgency forces chased us up the mountains almost daily, so I could not stick to a single place. When some of the fugitives were missing, I thought they were dead. Even when we were reunited, our reunion did not last long. I spent five to six months in the mountains. I still cannot believe the life I led. I have no idea as to what I wore nor what I ate. I remember sneaking into my old home that burned down and digging up food from a buried potato stash. Aside from that, I cannot remember much. It was not until I was imprisoned in Daegu that I got new clothes. Before that, I never took off my old clothes stained with blood from a gunshot. So, I had no time to care about my clothes. I was ironically relieved in prison because they fed me three times a day, albeit in poor-quality food. If there ever were someone who ordered me to run away, I would blame him. I had no one to blame because there wasn’t. From the start, I did not know what was happening or why I was being chased. They just shot anyone on sight, and I could not believe their propaganda saying, “You will be pardoned once you surrender.” I was pretty accustomed to my runaway life until late spring. It was around May. A soldier shot me in the middle of a creek behind Georin oreum in Hannam-ri. I was shot in my sacrum and could not move my legs and I was captured. A villager who was also captured carried me to the 5th Military Camp in Topyeong-ri.

“You’re not worth a bullet for killing!”

The soldiers began beating me with firewood, and they did not mean to just cause pain. I passed out and woke up the following day. Since I survived, they sent me to a refugee camp. I was sent to a button factory in Seogwipo.

Calling my name in the trial. That’s all?

I lived for more than a month in the button factory. Then, I was sent to an alcohol factory in Jeju-eup. About 15 days later, many people, including me, were sent on a truck somewhere. It was a huge auditorium packed with people and some soldiers, too. We were told to sit in a specific order, and soldiers began calling us one by one. They called my name, too. “Oh Young-jong!” I answered, “Yes, sir!” and told them my address, “657 Hannam-ri!” or something like that. There were hundreds of us. After they called our names, we were picked up by the same truck and taken back to the alcohol factory. I had no idea that what I had just gone through was actually a trial. Some years ago, when I was retried in the Jeju District Court, the lawyer asked me if I was tried before being sent to prison. I said I have not been tried. I said I was nowhere near a court. Then the lawyer asked me again, mentioning my name being called at Gwandeokjeong. That’s when I remembered the roll call-like event where soldiers called the names of the people in the auditorium. My goodness! That was a trial sentencing me to 15 years in prison.

Days in Daegu Prison: I had nothing to do with the National Guards Act!

People were lined up. We were bound by rope to the person in the front and the person in behind. Then, we were sent on a ship. At that time, I wasn’t walking properly. I never had any proper treatment for the gunshot wound in my sacrum. I still couldn’t move my legs well. My wound was festering and oozed rotten fluid. It was July, and the weather was hot. The smell was unimaginable. I was nearly dragged all the way to Daegu Prison. There was an unusual guy in the prison. He was not a warden but was free to do what most other prisoners could not. I think he was a model prisoner nearing the end of his term. He scraped off my rotten wound using a knife. It was painful, but the treatment was effective. The wound healed slowly, and later, I started walking.

The prison was spacious but was not enough to contain 300 people. We lacked cells and clothes. The 300 of us from Jeju were put in a single cell. The wardens asked about our charges and sentences, but none of the 300 people were able to answer. Some might have thought we were stupid folk from Jeju who didn’t even know their charges after being sentenced to 15 years in prison. I was told I violated Articles 32 and 33 of the National Guards Act. I had nothing to do with that!

I got my hair cut and heard that a new prison uniform would be provided. I felt like I had become a real criminal. I did not get a prison uniform, and perhaps it was because there were not enough for all of us. Instead, I was given an old military uniform. It was in the middle of summer in July and August, and it was hot in that uniform. They did not give us a single towel, so someone ripped the pocket from their clothes and used it as a handkerchief to wipe off sweat. Many people did the same, and the wardens were mad about it. I was somewhat relieved because we were all in the same cell. We could depend on each other.

By the way, the prison administration had us write a written conversion oath. Come to think of it now, I thought it was like a letter of apology for ending up in prison, which was naïve. Many prisoners did as they were told. However, some of the prisoners resisted to the last moment. Those who refused were handled individually. Usually, the wardens had us lineup in order of our prisoner numbers. But those who refused to write the conversion oath sat in a separate line. They must have known that the note was not merely a letter of apology!

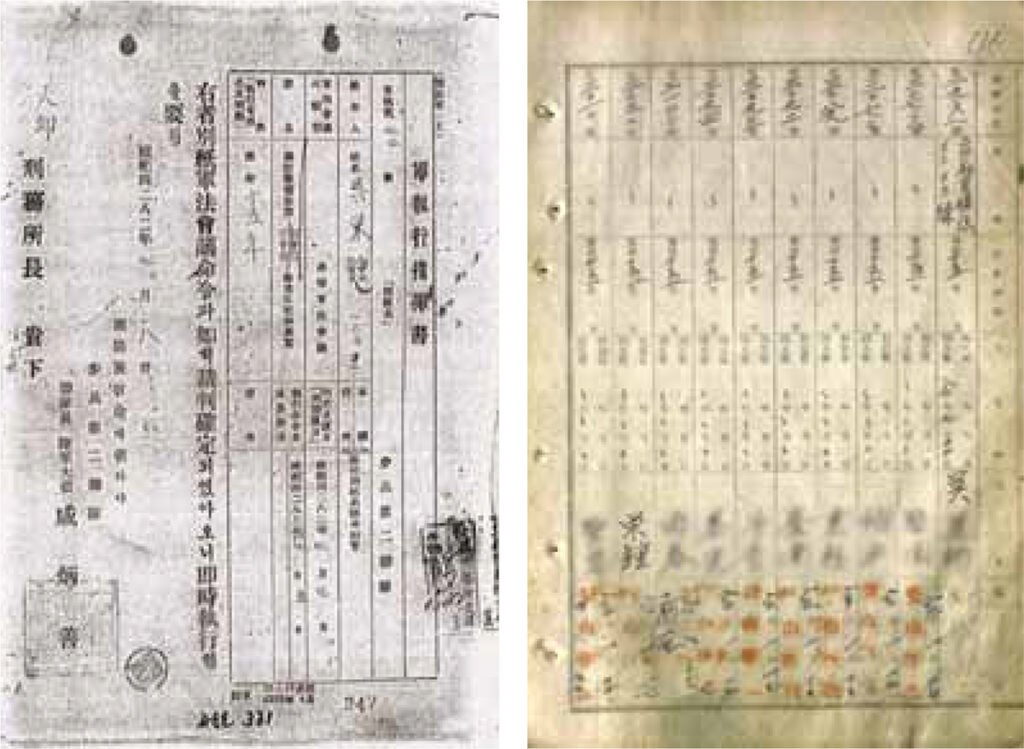

Military direction of execution, Daegu Prison in 1949

As per the National Defense Minister’s directive on July 18, 1949, Army Col. Ham Byeong-Seon, the commander of the 2nd Regiment, requested the execution of the sentence. On the right, Oh Young-jong’s name is written. It says, “We request an immediate execution of the sentence of the person on the right according to the court-martial decision.”

List of prisoners in Daegu Prison in 1949

Oh Young-jong, who was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment in violation of Articles 32 and 33 of the National Guards Act, is confirmed to have been confined in Daegu Prison on July 22, 1949, and transferred to Busan Prison on Jan. 17, 1950 (on the right).

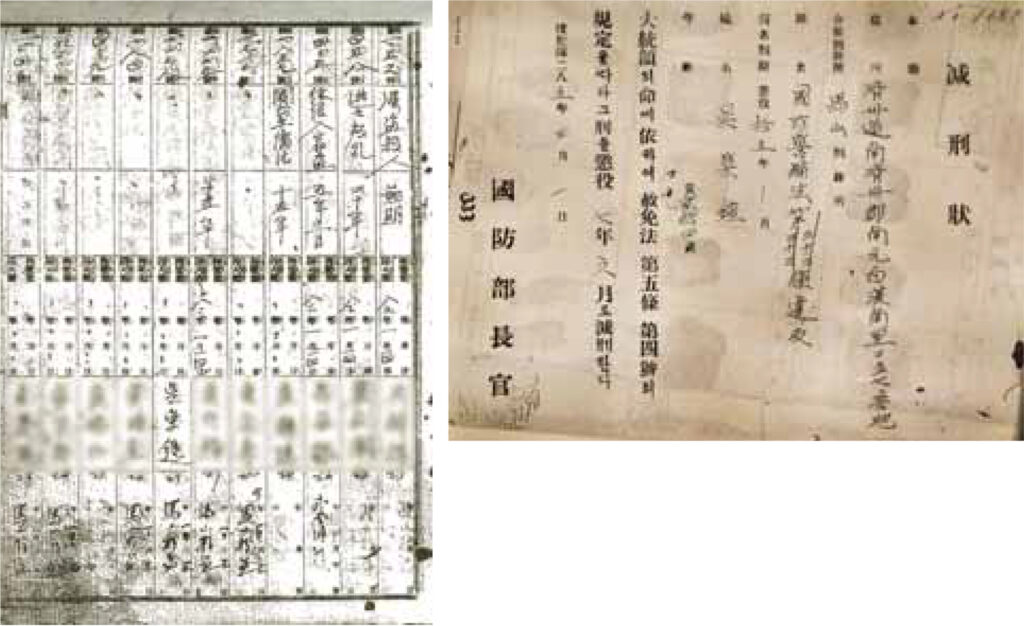

List of prisoners in Busan Prison in 1950

Oh Young-jong is confirmed to have been transferred from Busan Prison to Masan Prison on Oct. 3, 1950.

Remission Notice, Masan Prison

Per the presidential order, the Defense minister on March 1, 1952, remitted Oh Young-jong’s sentence from 15 years to seven years and six months, according to Paragraph 4, Article 5 of the Amnesty Act (Right).

Days in Masan Prison: Providence?

On Oct. 3, 1950, some prisoners, including me, were transferred again, this time to Masan Prison. The prison was almost empty. Wardens said the prisoners were all killed. They thought we were lucky and called us prisoners of providence. I began working at a factory, too. Prisoners who had skills were put to carpentering, and young prisoners who had little education were put to make rush mats. It was manual plaiting work. Every time we returned from the factory to the prison, the wardens checked our cells to see if we had smuggled any contraband or metal pieces in. The wardens would take our clothes off and stretch our arms out. The inspection of the prisoners from Jeju and their cells was rigorous. Prisoner numbers were written next to their cell door, and I saw “special inspection” markings on mine and those of my fellow Jeju prisoners. Prisoners from mainland Korea did not have such things next to their numbers. The strictness was supposedly because we were considered political criminals of Jeju 4·3.

Nevertheless, Masan Prison was a relatively comfortable place. All 300 prisoners were together in Daegu. We could not sit or stand properly. We could not talk to each other. The prison in Busan had 42 prisoners staying in a single cell, worrying about the calling at night, which was also a big problem.

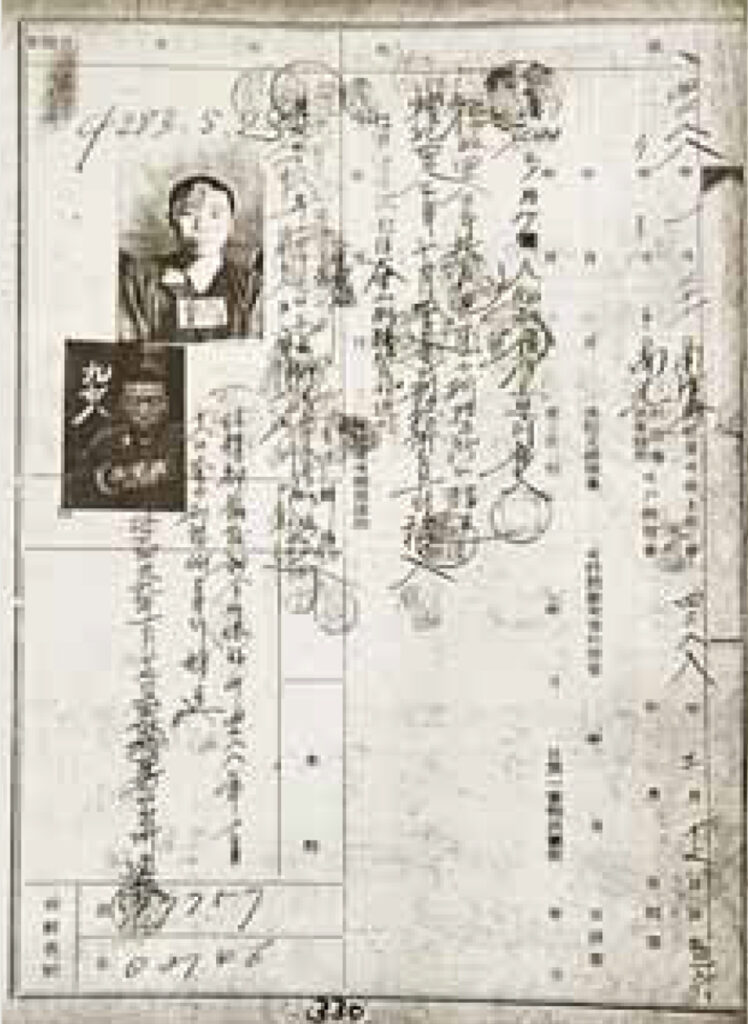

Identification Note, Mapo Prison

Top left is a photo of prisoner Oh Young-jong. Below the image is written, “Release of prisoner notice to Seogwipo (Police) Station on Jan. 17, 1956.” Top right is “Identification inquiry to South Jeju (Seogwipo) Police Station on Jan. 21, 1955, and family registers inquiry to Namwon-myeon Office on Jan. 21, 1955, which are to be replied to by March 17, 1955.”

That man is an ex-convict!

I was released from Mapo Prison in Seoul on Feb. 28, 1956. When I was at the court for my retrial a few years ago, I confirmed that I was put on military trial on July 3, 1949. After the trial, I was immediately sent to Daegu Prison. So, I was imprisoned for six years and eight months before my final release from Mapo Prison in Seoul. My initial sentence was 15 years, but it was halved. In addition, my sentence was reduced every year. In May, seniors in my family arranged my marriage. The wedding was in May. Many people had experienced the same hardships as me, so we all knew what had happened to one other. Few households were lucky to stay intact during the Jeju 4·3. The absence of my parents or the fact that I had been imprisoned did not matter when it came to criminal records.

One day, the police called me. They told me to bring two locally influential people as my reference. After that the head of the village visited me from time to time and began questioning me about who I had met and where I had gone. It was a small village, so there were no secrets. I had nothing to fear nor be ashamed of, so I did not care. But things went sideways whenever I had business outside the village. I rarely wandered off to Namwon unless there was a special occasion. It was much more comfortable going to Jeju, which is far off. Namwon, however, was a place where some people recognized my face. They often talked in whispers, saying that I was a convict. I did not like visiting Namwon.

On April 19, 2017, the convicted victims applied for retrials over the illegal courts-martial trials during Jeju 4·3. From the left, the late Hyeon Chang-yong, Oh Young-jong, Oh Hui-chun, and the late Yang Geun-bang (Up).

At the retrial on Jan. 17, 2019, a “dismissal of prosecution” was awarded, which is a dismissal of previous charges, and the former convicts celebrated with their families.

Mr. Oh Young-jong is in the front row, fourth from the left.