Arranged by: Cho Jeong-hee, Deputy Head of Research Department of the Jeju 4․3 Peace Foundation

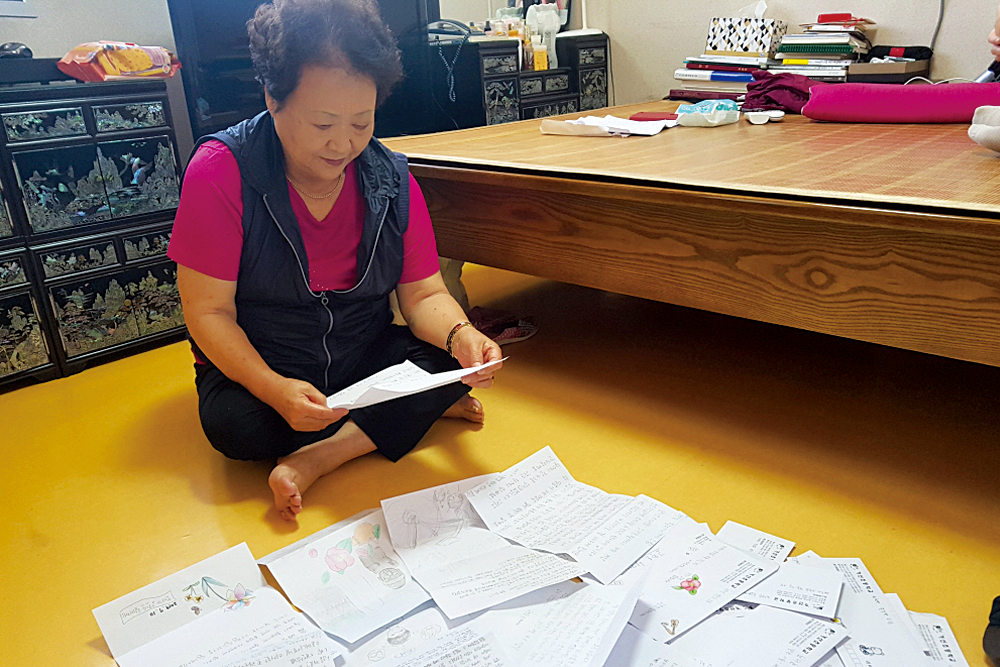

Elementary school students wrote letters of encouragement after watching a YouTube video feed of the UN Symposium

Lady Ko Wan-soon was born in Bukchon Village, Jocheon-myeon (now Jocheon-eup), Jeju, in 1939. Jeju 4·3 was a moment of life or death for the then-nine-year-old girl who was full of dreams and curiosity. It was only the beginning of her life when Ko had to give up every shred of her dreams.

On Jan. 17, 1949, at the site of the Bukchon Massacre, about 300 innocent neighbors were killed before her eyes. Her village was literally burned to ashes and was totally destroyed. Only the red blood glared in the view of the terrified girl. Now that 70 years have passed and she wishes she could forget… But whenever the red sun sets on that same field; the same Ompang Field she passes by every day, the dark red sky on the day of killing still looms over her. Even the slightest bleak wind reminds her of the odor and the screams from that day, as if they were coming back with the dreadful wind. The blunt blows to the head of her three-year-old little brother still strike Ko at the age of 80.

In May 2019, we paid a visit to Lady Ko in Bukchon Village and, with caution, told her that we would like to take her for testimony to the UN Symposium on Human Rights and Jeju 4·3 which was slated to be held at the UN Headquarters in the United Sates. The 13-hour-long flight, fear of speaking at an international conference, and the language barrier could have been uncomfortable for her. But, to our surprise, she accepted our request.

Ko gives her testimony at the UN Symposium on Human Rights and Jeju 4․3.

The United Nations is said to have been established for world peace and human rights. So, I should go. I should go and say with confidence that the killings in Bukchon Village were a cruel violation of human rights, that the massacre took all my dreams away, and that the United States and the United Nations should be held responsible for elucidating the truth of Jeju 4·3. Wouldn’t this make me feel less sorry for living 70 years longer than those who have already passed away under the shadow of false accusations?

Ko lost six members of her family, including her little brother, her mother’s sister and brothers, and her grandfather’s brothers. Ko, now leader of the Association for the Bereaved Families of Jeju 4·3 in Bukchon Village, stepped forward to speak at the UN Symposium on Human Rights and Jeju 4·3. <Editorial>

Jan. 17, 1949; the day on which dreams were taken away from a 9-year-old girl

I experienced 4‧3 when I was 9 years old. Looking backward, I used to be a dreamy, curious little girl. But 4‧3 took all my dreams away — and my life. As I had little chance to continue my education nor to be properly nourished after 4‧3, it changed my whole life.

On Jan. 17, 1949, the day of the Bukchon Massacre, the soldiers burnt down our houses and ordered the residents of my village to gather in Bukchon Elementary School. My house was located on the inward side of a narrow neighborhood path. As the soldiers had set fire to the outside of the houses, my house quickly filled with smoke. The footsteps of the soldiers went away, and then the baby next door burst out crying. Then the sparkling blade of a knife pierced through the door of my house. Discovered by the soldiers, I was dragged out into the street only to see the sky covered with black smoke and my village turned into a sea of fire.

Machine guns blast away on the schoolyard of Bukchon Elementary School

The school yard was already filled with people. “Why are there so many people here?” I thought, looking around, wondering with curiosity. Then, three machine guns installed on the other side of the school’s fence jumped to my eyes. My family, taken there later than others, sat not far from the school’s main gate.

But I saw a line of men at the front of the school yard, their heads only appearing above those who were sitting in front of us. Again, I became curious. “We are all sitting, and how can I see their heads?” I craned my neck, balancing myself on one foot. There was a soldier on the teacher’s platform with several male adults standing in front of him. One, two — I counted their heads, in spite of myself, and “Bang bang bang! Bang bang bang!” I heard sudden gunshots. And the heads I had been watching were gone. Could the rifle shots have been a signal? For right after, “Rat-a-tat! Rat-a-tat!” rang out. The machine guns placed over the fence started blasting away.

A baby at the breast of a dead mother

On that day, I felt like a rat in a trap and the soldiers intended to kill us all. Evading a hail of bullets on the school yard, my mother, carrying my 3-year-old brother on her back, held the hands of me and my sister, who was six years older than me, and stuck her head and ours on the ground. “Rat-a-tat! Rat-a-tat!” continued the guns. The wailing scream. People flocking here and then moving there, crawling on the ground like dogs, in order not to be killed. After a while, the gunfire stopped. At last, I raised my head from the ground to see a female’s feet in rubber shoes in front of my eyes. “We are scared and everything is in chaos, so why is this woman lying here?”

t that instant, I felt something sticky on my right palm. It was blood, scarlet red. Red blood flowing out of the young woman, who was shot to death. On her bosom was hanging her baby, looking for milk.

The death of my three-year-old little brother

Shocked to see the blood on my hands, I kept shouting, “Mom, it’s blood! Blood! I’m scared. Let’s go home. Let’s go home.” When my little brother started crying, one of the soldiers spat vulgar language at us: “Son of bitch! You die now or later anyway,” and beat my brother’s head with a club he had been holding.

Even before my mother could try to stop him, I heard “Bam! Bam!” the sound of his skull smashed. And my little brother could no longer whine or cry. He lost consciousness, drooping down my mother’s back. In the end, without being able to receive proper medical treatment at a hospital, he died in March 1951, after years of suffering from the fluids having collected in his head.

Dragged to Ompang Field with my mother and older sister

After blindly firing their machine guns, the soldiers, now with long poles tied with a strap in the middle, shouted repeatedly, “Come out now if you are going to Jeju-eup!” Those who thought escaping the school yard was the only way to survive scrambled to follow the soldiers. The soldiers placed their poles on the ground, dividing the playground from east to west, as if drawing the 38th parallel.

My family sat in the eastern section, not knowing on which side we would have the greater chance of living. For those who were separated from their families by the sheer number of people in the school yard fell into chaos searching for their family members. This time, the soldiers started beating us with their clubs. I held the hands of my mother and my sister tightly, trying not to lose them. The soldiers took tens of people out of the yard, one group after another, saying, “We are going to Jeju-eup.”

But soon after they left, there came the sound of “Rat-a-tat! Rat-a-tat!” and it was repeated several times. My sister said, “Mom, chances are we are all going to be killed. Let’s not go out there.” By then, everything was chaos, with people trying to return to the school yard. Pushed in different directions by those who tried to get in the yard and those who were dragged out, my family and I were taken to Ompang Field.

Cease fire! A narrow escape from death

Even now, walking in front of Ompang Field reminds me of the heap of the dead bodies left there. A body with its face down, a body with its head between its thighs, a body with a foot in its mouth, and a body curled up with a hand holding its hair pulled back into a bun with a silver hairpin. How painful and unbearable their deaths were, with their bodies twisted like that. The more I think about it, the more miserable I feel and I cannot help but cry.

But there is a more heartless memory. Probably because it was winter, and the sun hid behind the clouds and only appeared again as a sunbeam. And with every sunbeam, the blood flowing from the bodies was absorbed into the ground. The soil of Ompang Field gradually turned dark red, glittering like glass beads with the reflection of sunlight. That dazzling, sparkling red blood… Having had us sit in a row, the soldiers began loading their guns behind us. “Clickety-clack.” With the sound of the iron tool, my mother grasped tight my and my sister’s hands. Her hands were trembling. Resigning myself, I thought, “Oh, this is the end!” Then, from a distance, I heard someone shout “Hold fire!” Then the soldiers swore, “You, suckers, will live longer than flies.” The foul language stabbed me in my little heart. That is how I survived, at death’s door. Now, am I living a worthless life as a fly does?

On my way home from the school yard, the heat coming from our neighborhood path nearly suffocated me. Though it was winter, I sweated buckets. The burnt houses and the burnt bodies and the unruly cows and pigs that ran out of the houses — Now, 70 years removed, I wish I could forget that scene… But, every day when I pass by Ompang Field, the dark red sky on the day of the killing still haunts me, especially when the red set on the field. Even the slightest bleak wind reminds me of the odor and the screams from that day, as if they were coming back with the dreadful wind.

The deaths of my aunt and uncles, who were my pride and joy

The next morning when blizzards came swirling, the soldiers ordered every villager to gather in Hamdeok. Following the order, we went over to Hamdeok Village where the military forces were stationed. On arriving there, my mother searched the dead bodies for her sister. When my aunt was taken away on a military truck from Bukchon Elementary School the previous day, she was, for sure, wearing a yellow traditional jacket. But, when we discovered her body in the sand pit of Hamdeok Beach, we could see what miserable and unspeakable death she suffered. Her face, her breasts and her genitals had been stabbed and cut by knives. Back in my childhood, I felt proud of my aunt and uncles. However, after my aunt was brutally slaughtered, one of my uncles was imprisoned, without any sign of his whereabouts up to this date. He was my mom’s eldest brother, a math teacher at Jeju Middle School, and an elite who had graduated from the Department of Mathematics at Tokyo University, Japan.

One day, immediately after national independence, a small helicopter landed on the school yard of Bukchon Elementary School. The next moment, my mother’s eldest brother was speaking to a U.S. soldier who appeared out of nowhere. The other children and I flocked to see the helicopter, and I was so proud of my uncle, who was talking to the soldier in English. The box of canned food and chocolate that the soldier left us made feel great. But my uncle, who used to be my pride, the pillar of my family, was later taken somewhere during 4·3. We do not even know where he died.

I, an 80-year-old woman now, still feel sorrow for my lost dreams.

The winter that seemed to never end eventually passed, and finally spring came. People said 4·3 is now over, but nothing changed. Nobody helped us rebuild our burnt houses. Nobody bought us new household goods and furniture. Nobody gave us clothes to wear, nor rice to eat. My aunt and uncles, who were killed indiscriminately, were never brought back to life. Instead of our burnt houses, all of my family members lived in a make-shift hut. Having nothing to eat, we had to collect seaweed from the sea and grass from the mountain. Mugwort and green laver are still my least favorite foods. Still, I desperately wanted to continue my education. I had no money to buy a school uniform and had to fabricate one on my own by dying a wheat flour sack in black. I entered 3rd grade in my middle school but never made it to graduation because of economic difficulties.

If I had continued, I could have attended the 11th graduation ceremony of Jeju Girls’Middle School. Until now, I find it regretful to have failed to study further due to poverty. If I had been allowed to finish at least middle school, wouldn’t I have been able to achieve at least one of the many dreams I had? Now that the long years have passed, and that 9-year-old girl has become an 80-year-old grandmother, I still feel pity for myself and my lost dreams. – The end. –

Ko Wan-soon gives her testimony at the entrance of Ompang Field where bodies were piled during the Bukchon Massacre. She could not even set her foot there as it brought back the memory of the blood-filled field 70 years ago.