Testimony of Jeju 4·3 by Ko Jeong-ja

People walked the same roads and drank the same water as we did because there was none other…

Ko Jeong-ja (born in 1932 in Anseong-ri, Daejeong, now lives in Boseong-ri, Aewol)

To Ko, Jeju 4·3 began when her father went missing. After her father disappeared, Ko Jeong-ja, who was once called the daughter of Chief Ko, or Secretary Ko, was now treated as the daughter of a rioter.

With Ko Jeong-ja’s father missing, she and her family members were treated as rioters, resulting in her grandfather and her sister being killed, leaving her and her two younger siblings to survive and suffer the consequences of being related to a fugitive.

But she could not blame her family. How could she resent her dead mother? How could she resent her father, whose body is yet to be found? How could she hold a grudge against those who ignored her, fearing the “traitor?” Who’s fault was it that she became a criminal? Jeju 4·3 made Ko Jeong-ja’s life miserable and lonely.

Interview and arrangement by

Cho Jeong-hee, Head of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation’s Memorial Project Team

At around the time when Jeju 4·3 occurred, I lived with my family that included my grandparents, my father, my elder sister, my little brother, my little sister, and me. I was 17. My elder sister was 20. My little sister was 14, and my little brother was 10 years old. The ancestors of my family lived in the Anseong area a long time ago. Still, they moved to Inseong after my mother fell ill after giving birth to us. After we moved to Inseong, my mother lived three more years and died in December of 1945, the year of liberation.

My mother died, bleeding and soiling herself

I still do not know what made her sick and die. I know that her symptoms were the same as those who die of cancer. So, I can only imagine now that cancer killed her. At first, my mother told me that the lower part of her belly ached. Later on, she asked me to repeatedly stroke her stomach. I think the mass of cancer grew big and filled her stomach. Now we do operations and treatments to get rid of cancer, but there was nothing like that back then. So, as the mass of cancer grew inside my mother and eventually festered, she defecated blood. Every morning, I washed my mother’s blood-covered clothes. We have a water supply system now, but back then, we had to get water from a pond. Days were cold in the winter and I had to wash the clothes myself using that icy, cold water. It is as if my hands still remember that cold water and become chapped every winter.

My mother was never given a chance to see a doctor. I did my best to hold her funerals, but that will never be a comfort for my mother. She died too young, at the age of 40. My father was only 39 at the time.

[The late Cho Byeong-hyeong (third from the left, on the last row), Ko Jeong-ja’s husband, one of the first graduates of Boseong Elementary School. Ko’s father had worked three years constructing the facility]

The beginning of Jeju 4·3

My father was an outgoing person. People called him “Chief” or “Secretary.” He was literate and proficient in reading Chinese characters. He used to teach reading, attend to village affairs, and many of my father’s pupils would visit him day and night back when we used to live in our old house in Anseong.

About a year after my mother died, I heard that the police had arrested my father. At first, he was sent to the Seogwipo police station. Later, he was transferred to the Jeju police station. Fortunately, there was someone in a high position in the police among the relatives of our Ko family, and my father was released. My father came home and stayed there for a while. But the police wouldn’t let him be and kept visiting him. That was when Jeju 4·3 began.

“Where is your father? Tell us!”

A police force from the Daejeong substation rushed into the yard with rifles. I was so afraid that I could barely stand. They fired into the ceiling to smoke my father out of hiding and searched through our house. We were in a desperate situation. This mean gang was a supportive police force for counterinsurgency operations dispatched from the mainland. They pointed their guns at my elder sister and me and dragged us to the substation.

“Where is your father? Tell us, or I’ll shoot you to death!”

I didn’t know where my father was. And if I said I did not know, I knew they would beat us. However, it was the only thing I could say to save myself. If I said I did know, they would have killed us. I was released the night of the arrest, but my elder sister was detained and harassed for three days. She was tortured in place of our dead mother. They did not treat us as humans but animals like dogs and pigs. I would say that ‘I live today’ only to ‘die tomorrow.’

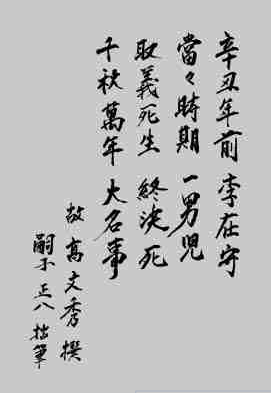

[“Lee Jae-su, in 1901, the year of ox / As a man with honor and dignity / Died doing the righteous thing / Leaving a huge trace in history.” A Chinese poem about Lee Jae-su, leader of the Jeju Uprising in 1901, written by Ko Moon-su, the father of Ko Jeong-ja and Calligraphed by her brother, Ko Jeong-pal.]

The families of fugitives must be annihilated!

The day of Oct. 19, 1948 was a day our family was to perform ancestral rites. My elder sister returned from a village meeting. She did nothing to prepare for the rites but cried.

“The families of fugitives must be annihilated!”

After martial law was imposed, a command was proclaimed to exterminate all fugitives and their families. My elder sister could not help but cry. Unlike his granddaughter, my grandfather was quietly preparing meat for the rites. He knew there was nowhere to run. Where would he run to? Does he have anywhere to run to? Will he be able to last long as a runaway? No, he would not. We performed the ancestral rites in tears. The following day, my grandfather was called to cut trees. Back then, the substations would call people out to cut trees. My grandfather, as always, went out with his saw. After a while, a young man from the village came to escort my elder sister and me to the police force. He said it was an order, so we had to follow it.

[Tablet enshrined in the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park for Ko Moon-su, who went missing]

Who is the eldest one?

We were sent to Dongheonteo, where the east building of the old magistrate’s office stood. It is where Boseong Elementary School is located now. There was nothing but fields at the time of Jeju 4·3. People from the five villages of Boseong, Inseong, Anseong, Gueok, and Sinpyeong were gathered there and the field was crowded.

“Daughters of Ko Moon-su, come out!”

“Who is the eldest one?”

At the time, I was about the same height as my sister. I was too afraid to say anything. My elder sister held my hand and said, “I am.”

I was left in the field, and my sister was sent to Hongsalmungeori (the Seogwipo police station)

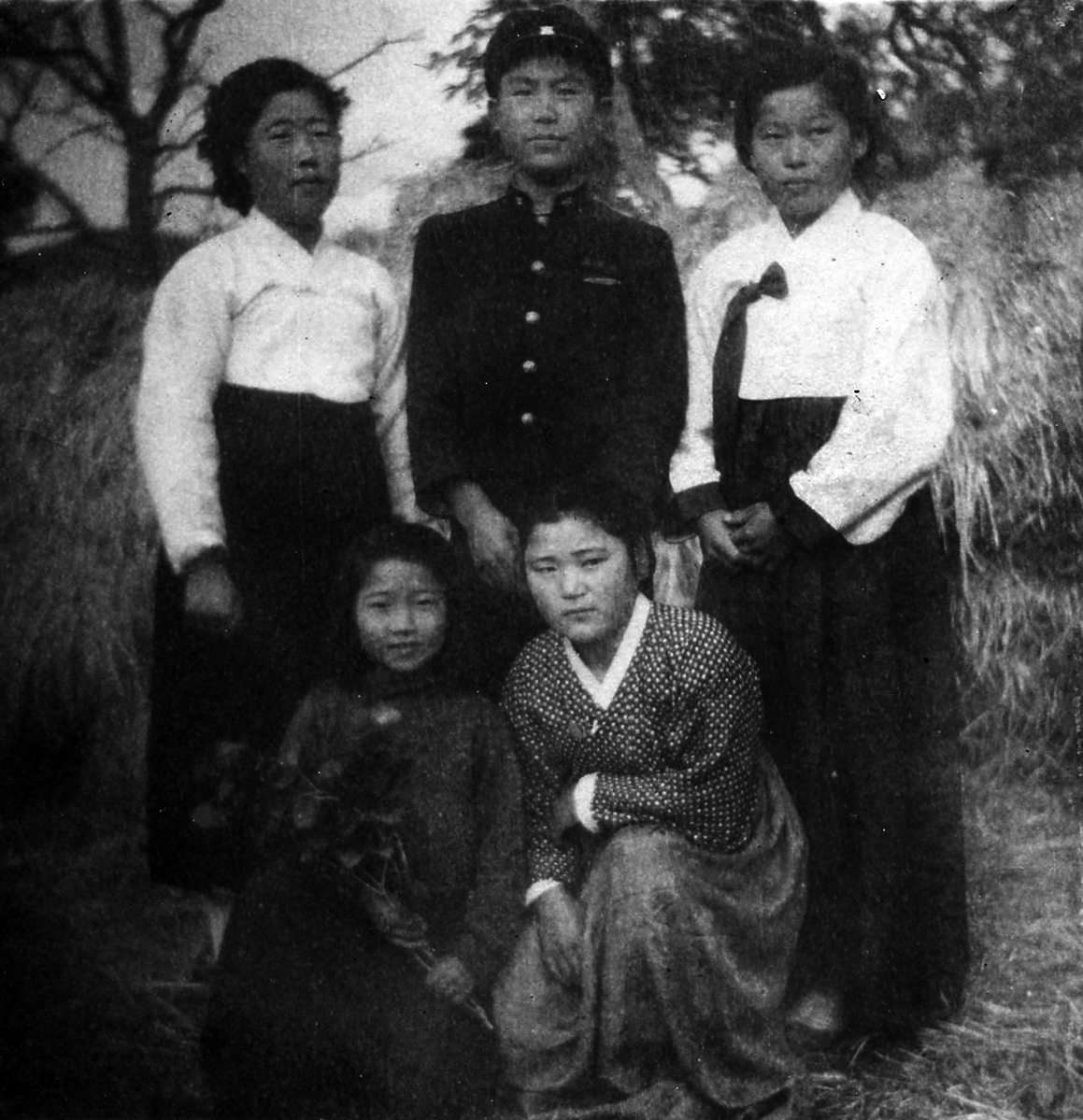

[Ko Jeong-ja with her younger siblings and her cousins. Ko Sook-ja, the younger sister, is in the front row on the right side. Ko Jeong-ja is in the back row on the right side. In the middle, Ko Jeong-pal, the younger brother, is wearing his school uniform]

The deaths of elder sister and grandfather (the massacre of the families of fugitives in Dongheonteo, Daejeong, on Nov. 20, 1948)

I could hear the soldiers marching. They were bringing people into the field of Dongheonteo. There were about 20 people. I could see my grandfather, who had left to cut trees, and my elder sister, who had been sent to Seogwipo. People stood in line before us, and the soldiers stood behind them. They were wearing white helmets and holding rifles. A soldier behind each person. I was so afraid that I did not dare to see what would happen next. I closed my eyes.

“Whee!”

“Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang!”

As soon as a whistle blew, gunshots roared. And that was it. I cannot remember anything after that. Somehow I was able to recover the bodies of my grandfather and my elder sister, but I cannot remember how I did it. A few relatives who helped with the temporary burial lived nearby, but I am unsure if I ever undressed their bloody clothes.

Why do you take from us?

The police, now tired of killing the fugitives’ families, began burning down their houses. The burning had already happened in Sinpyeong and Gueok. And it could have been our turn at any minute. So, what did I do? Those who survived have to survive, so I hid some grain.

I dug up the garden and buried a large pipe of bamboo. I poured rice into it. On top of it, I put strings of sweet potatoes to cover the bamboo. Lastly, I put the remaining grain in small jars and put the jars into gaps in the garden wall.

Suddenly, the police ordered us to fortify the village. They wanted the people to build a wall that surrounds the villages of Boseong, Inseong, and Anseong. We had to collect all the stones we saw, including those from the stone walls. When I was working near my house, the people took stones out of our house and garden walls. However, they did not just take the stones but the grain we hid in the wall too. How coldhearted!

“Why are you taking our food?”

But I could not say this even when they took the food right in front of us. We were the family of fugitives. We were as good as dead to them.

[Ko Jeong-ja, right, with her friend Ok-hwa]

Would it be possible to recover my father’s body?

At the time, the police force organized a special force composed of the village’s young men. These special forces went everywhere to root out their enemies, and they told me about what was happening in the mountainside. They told me about my father’s death. I did not know where he died or how I could recover his body. There was nothing I could do then. All they told me was to perform his funeral ceremony on March 12 by the lunar calendar. I can only do as I was told, believing that his death was confirmed.

I got married at the age of 20. When my eldest son was two years old, I heard that a person by the last name of Ko had come back to Sinpyeong from a prison on the mainland. I went to Sinpyeong to see him, carrying my two-year-old son. The man said, “It is obvious that he died. However, I do not know where he was buried. Three people went out to bury him, but I was not among them. All three of them were killed, so I have no idea. I only know where Kang was buried.”

I knew Kang was one of my father’s pupils. The man from prison said Kang was buried near a rock at Doloreum in Mount Halla. If my father had been with Kang all along, maybe he would have also been buried somewhere near Doloreum. If only I could find his body… But it has been so long since then.

[Ko Jeong-ja at the Civil Defense Training Camp on April 5, 1951 (second from the left at the front)]

Trained as a member of the Civil Defense Force as a substitute for men

As things cooled down a bit, they conscripted all the men. They tried to use women, too, and organized a women’s civil defense force. There were 30 unmarried women conscripted from the five villages of Boseong, Inseong, Anseong, Sinpyeong, and Gueok. We were trained at the squire house in Boseong. We were trained to shoot with wooden rifles, as well as to perform bayonet skills, butt-plate strikes, and to crawl. It was military training. I got up at five in the morning, and the schedule was full of military training. But this was a piece of cake, running from here to there, rolling and crouching. Do you know what the hardest part about training was? It was learning.

The trainers would write down the names of the military generals on a chalkboard that would become full of the names of people such as the national defense minister, the prime minister, and so on. We had to write all of them on a notepad. After that, the trainer gave a short lecture and then erased what was written on the chalkboard. This was not the most difficult part. Since this was a military camp, we did roll call at night. The trainer would bring a club with him and point it at a trainee. The trainee would then have to explain what she had learned on that day. If she hesitated or did not know the answer, then she was hit with the club. Every night, I was scared. My lips would go dry. I did not know much about reading or writing because I had not been to school. I went to night school for a while, but that did not help much. I did my best not to get called out during roll call. In the meantime, my reading somehow improved. I still clearly remember one of the names I had to memorize: Jeong Il-kwon. You have no idea how much I tried to memorize that name.

[Ko Jeong-ja has lived her entire life in the house her father used to work in.]

Ko is still branded as a family of a fugitive

All I had after Jeju 4·3 were my grandmother, who could hardly move, my two younger siblings, and the brand that says, “you are a family of the fugitive.” It was a lonely life, having no one to depend on.

“People walked the same roads and drank the same water as we did because there was none other.”

It seemed people did whatever they could to ensure they would not tread down the same path I was walking. They would not share the village’s water with us. We were branded as the families of fugitives. They were afraid of what might happen if they showed us any kindness. That brand lasted a long time.

But I do not blame anyone. Who should I blame? My dead mother? My dead father, whom I could not even find the body of? Who is to blame? Everyone suffered and tried to survive Jeju 4·3, and I cannot blame them.