We couldn’t even discover his body

This is the only written proof of his life,

evidence that ‘he’ existed, living here in the old times,

a testament to a man named Ko Chang-man, once alive.

His palm-sized postcard,

with the pointed handwritten lines,

is now as aged as the knotted hand of his little brother.

The paper discolors with the uncaring passage of time.

But it keeps his memory and love ever more alive.

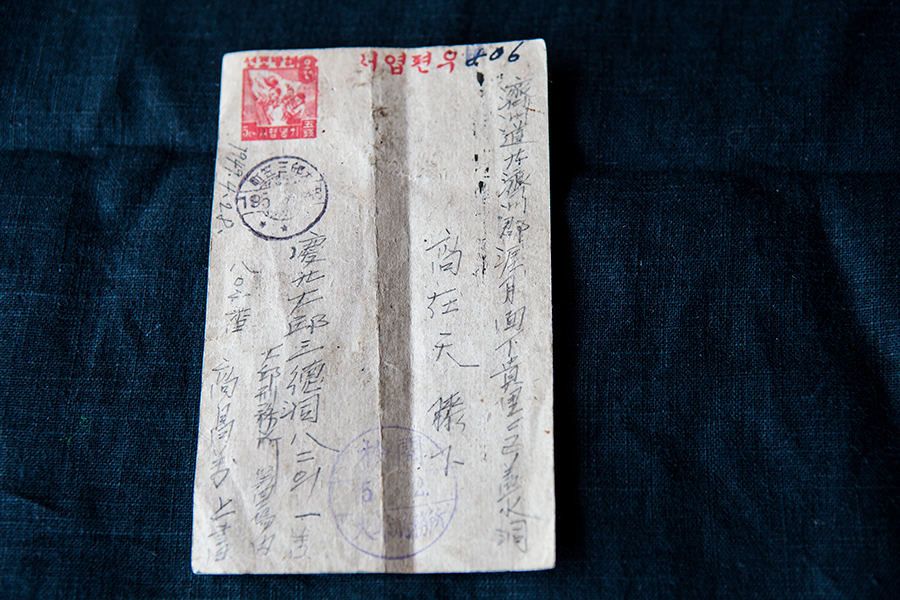

Postcard_ front

A postcard to commemorate national liberation, dated April 28, 1949, brings back the memories of 70 years ago.

Writing the address of his father to whom the postcard was sent, could Chang-man have possibly imagined that he would never be able to return to his beloved home in Jeju?

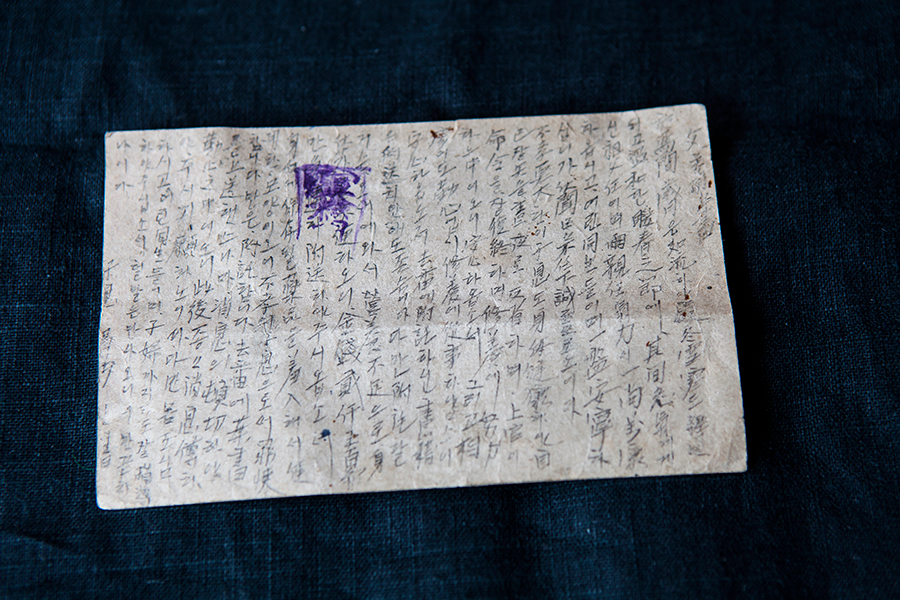

Postcard_ back

Chang-man sent this postcard from Daegu prison. It is Chang-seon’s only remaining relic of his father, and the last sentence his father wrote on it became his last words: “I still have many more things to say to you, but I should stop here.” With all those things left unsaid, Chang-man soon became one of the missing.

“From November 1948, an army battalion was stationed at Oedo Elementary School. The troops convened the villagers able to work and collect firewood for cooking. In fact, it was all a trap set up to kill young men. My father said he would go and that we should stay home. But, my eldest brother left home, as he said he would during breakfast that morning. An estimated 50 villagers responded to the call from the battalion. In the afternoon, only the elderly returned and the young ones went missing (without any news, as if they were dead). After my elder brothers were arrested, the soldiers visited my village and killed people day after day. They just checked off the name of the resident and ruled that they were sentenced to 15 years in jail for aiding and abetting the rebellion. That way, people were locked up in a classroom of Buk Elementary School, without any investigation nor on any grounds. The next day, they were all taken elsewhere by boat. But the following year, we received a postcard from my brother, sent from Daegu prison. That was when we learned that the military forces didn’t just dig a hole and kill him as we thought they had.

When the Korean War broke out, however, my brother went missing once again. He was conscripted for forced labor, but the army abandoned him when retreating from a battle. The very spot where he went missing was turned into a reservoir. We couldn’t even find his body.