“I Passed the Police Exam 50 Years Ago—Will They Issue an Appointment after All This Time or What?”

Kim Soon-ja (born 1948 in Susan-ri, Seongsan-eup, living in Jeju City)

Kim Soon-ja never knew her father’s face. Her father was taken by soldiers, soon after Kim was born, before he could even hold his youngest daughter. He was executed at Seongsanpo’s Teojinmok. Growing up without a father meant enduring constant hunger, but she never gave up on her studies. Just as she was about to achieve her dream of becoming a police officer, the forgotten story of her father was suddenly revived, forcing her to abandon her aspirations. What followed was 50 years of a life that was painfully distorted. Having only recently escaped the vortex of suffering and misfortune, Kim now reflects on how she has come to understand her father’s tragic death, even if it is late.

– Editor’s Note

Interview and Compilation: Cho Jeong-hee, General Affairs Team Leader, Jeju 4‧3 Peace Foundation

Moving to Beophochon

I was born in 1948 in Susan-ri, Seongsan-eup. I have very few memories of my childhood, but I do remember holding my mother’s hand and walking briskly from the eastern town of Susan-ri down to the southern town of Beophochun in Seogwipo when I was about 9 or 10 years old. What would a child know? I was just excited about going to a new place, filled with anticipation. I had no way of understanding my mother’s feelings back then—how she must have felt, fleeing her hometown in a rush, with only a small bundle on her back and tightly gripping her young child’s hand.

My father was the eldest son in the main family line (“Jongson”). My mother gave birth to two sons and then two daughters—four children in total—and I was the youngest. When we moved to Beophochon, it was just second oldest brother and me. My eldest brother, being the Jongson, wasn’t allowed to leave the main family house. My eldest uncle’s wife firmly held on to him, making sure he couldn’t leave. As for my sister, it seems she had gone to the mainland to work somewhere.

When we arrived in Beophochon, there wasn’t a single room for the three of us to stay in. Why did we come to such a harsh place instead of staying in Susan-ri? At first, I didn’t know why we ended up here, but it didn’t take long for me to figure it out—even without anyone explaining it to me. It was because of the rations. Back then, life was so hard that we relied on rations, not from Korea but sent from the United States, and Beophochun was one of the places where they were distributed. Cornmeal and wheat flour rations were all we had to make porridge or gruel to barely survive. Beophochon was a village formed by people like us, drawn by the promise of rations. It was a place where the poorest gathered—a village of the poorest. That’s what Beophochon was.

Starting 3rd grade at Topyeong Elementary School!

While living in Beophochun, I went to school for the first time in my life. When we lived in Susan-ri, I had never even been near the school gates. I was so envious of the neighborhood kids with their backpacks going to school that I begged my mother over and over to send me, too. Eventually, she went to Topyeong Elementary School to see if they would accept me. Since I was old enough to graduate elementary school but hadn’t even started yet, I’m sure the school didn’t know what to do with me. They couldn’t accept me into the first or second grade, so I had no choice but to start in the third grade. Even then, I was one or two years older than my classmates. Though I finally got to go to school, I had never learned how to read and write. I couldn’t even write my own name in a notebook.

“Please write my name here for me. It’s Kim Soon-ja, 3rd Grade-Class 1.”

I had no choice but to ask the kid sitting next to me to write it for me. But then they spread the word that I was in the third grade and couldn’t even write my own name. I can’t tell you how embarrassed and ashamed I felt. At first, I couldn’t understand anything the teacher said, couldn’t take dictation, and just sat there blankly. But by the second semester, I started catching up with the other kids. By the time I reached the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades, I became the best student in the class. Back then, everyone’s skills were pretty similar, so it wasn’t that hard to stand out.

1969 Seogwi Girls’ High School 5th Graduation Photo (Kim Soon-ja, second from the left in the third row)

Selling firewood and charcoal to pay for tuition

After I graduated from Topyeong Elementary School, then my mother wouldn’t let me rest, insisting that girls also needed an education. Even though we didn’t have a penny to spare, she made sure I continued my studies. I enrolled in Seogwi Girls’ Middle School. I’m not sure of the exact distance from Beophochon to Seogwi Girls’ Middle School, but it must have been about 10 kilometers. Would there be any transportation? Even if there were, how could I afford the bus fare? I just walked 20 kilometers round trip every single day to attend school.

“Mother, I’ll sell firewood so I can keep going to school.”

On Saturdays and Sundays, it was straight to the mountains to gather wood—always with a saw in hand. We’d cut down dead branches, split them in half, and make firewood. Then we’d carry the firewood to Seogwipo to sell it. I’d wrap my school bag and uniform in a bundle and place it on top of the stack of firewood. From Beophochon to Seogwipo was over 10 kilometers, and I carried the heavy load of firewood on my back the whole way. The road wasn’t paved; it was rough, with uneven stones clattering underfoot. And it wasn’t just firewood we sold—we also made charcoal because it was in high demand back then.

“Buy firewood! Buy charcoal!”

I wandered from house to house, selling firewood and charcoal. Occasionally, one of my classmates would pop out unexpectedly.

Kim Soon-ja during a cooking class at Seogwi Girls’ High School

“You know what? Soon-ja came to my house to sell firewood!”

What could I do, even if rumors about me spread all over school? Was there anyone else to do it for me? Walking around without even eating breakfast, it would quickly become lunchtime. If I couldn’t bear the hunger anymore, I’d buy a steamed bun. Not two or three, just one. It wasn’t just because I didn’t have money—I couldn’t bring myself to spend it. After eating that one steamed bun and selling all the firewood, only then would I change into my school uniform and head to class.

I never bought even a single pencil with money from my own pocket. We didn’t even have enough money to buy rice to eat, so where would I get money for school supplies? When I needed a pencil, I had to sell firewood first. The money from selling firewood was used to buy pencils, notebooks, and even my school uniform. Back then, survival was more urgent than feeling embarrassed or ashamed. I had to survive.

Becoming a teacher at Yeongcheon Branch School of Topyeong Elementary School

I must have been pretty good at studying. After graduating from Seogwi Girls’ Middle School, I went straight to Seogwi Girls’ High School. Both in middle school and high school, whenever it was English class, the teachers would always ask me to read out of the book first. It was the result of memorizing English vocabulary while walking those 10 kilometers every day, probably?

After graduating from high school, I wanted to go to college, but there was no way to afford the tuition. Even my middle and high school fees were barely covered by selling firewood and charcoal, so college tuition was out of the question. But having graduated high school, I couldn’t just keep selling firewood for a living. I started thinking that I needed to find a job where I could earn a salary.

Back then, you didn’t need to go to college to become a teacher. If you graduated from a teacher training institute, you could teach at elementary schools. So, I enrolled in a teacher training institute and, after completing the program, was assigned to Yeongcheon Branch School of Topyeong Elementary School. It was a small school located at the entrance to Beophochon, with only grades 1 through 4. From 5th grade onward, the students transferred to Topyeong Elementary School. Since there was only one class per grade, there weren’t many teachers. I worked at Yeongcheon Branch School for about five years straight. Getting transferred to another school would have required renting a place to live, but at that time, I couldn’t even afford to rent a house. So, I never considered moving to a different school.

I found teaching kids to be a perfect fit for me, and the students really responded well to me. But at some point, rumors started swirling, and the atmosphere turned unpleasant. I didn’t know why at the time, but it felt like people were whispering about me behind my back. Whenever I went to Topyeong Elementary School for events, the other teachers seemed to exclude me—like they were giving me subtle hints. They didn’t say anything outright, but I could feel it in the air. It was clear they wanted me to quit.

Passing the women’s police exam!

I decided to quit teaching and started preparing for the women’s police exam. It wasn’t because I particularly wanted to be a police officer, but because I needed a job where I could earn a steady salary. At that time, finding work and earning money as quickly as possible was my top priority. I took the written exam, passed the interview, and received my final acceptance notification. It wasn’t an easy test—There were more unsuccessful applicants than successful ones. After passing, they put us through training before assigning us to posts. I completed the training without any issues and was eagerly waiting for my appointment. But no news came. Everyone else who passed with me received their assignments, but I heard nothing. That’s when I started to suspect something was wrong and decided to visit the training center to find out what was going on.

“You’re not going to get an assignment. It’s best to just give up.”

When I asked why I hadn’t received an assignment, at first, they said nothing. But I kept pressing them, and finally, they told me I wouldn’t be getting an appointment. It made no sense—I had received the acceptance notice and completed all the training for successful candidates. I demanded to know the reason and wouldn’t back down. Only then, reluctantly, did they tell me. It was because of my father!

“Say nothing about it!”

It was strange from the beginning. When I said I wanted to take the women’s police exam, my mother tried to stop me. She didn’t say much when I decided to go to the teacher training institute, but the moment I mentioned the police exam, she kept insisting that I give up.

“I couldn’t even stay a teacher, and now you stop me from being a police officer? I’ll take care of it on my own!”

I felt hurt by my mother’s opposition, but I still thought she’d be happy for me if I passed. However, even when I showed her the acceptance letter, she didn’t speak a single word of praise. Honestly, I felt disappointed in her. But when I didn’t get the assignment, I finally understood why she had tried to stop me. My mother had known all along—she knew I would never be allowed to become a police officer!

“Why is it that I can’t even be a teacher or a police officer because of my dad?”

I was so angry and frustrated that I felt like I had to vent to someone—anyone. Back then, even in big towns, there were only about five or six girls per grade in high school. Kids like me, who came from poor families, couldn’t even dream of going to high school. I sold firewood and charcoal, worked so hard to finish my studies, but now I couldn’t get a job. How could I not feel furious? The anger just kept boiling over, and I couldn’t hold it in. I ended up taking it all out on my poor mother. But even then, she never explained anything—she didn’t tell me how my father died or say something like, “Your father’s death was unjust, so don’t blame him.” She didn’t say a word about it, one way or the other.

“Say nothing about it.”

That was the only thing she ever said. No matter how much I yelled or cried in front of her, all I could hear was, “Say nothing about it.” I know that it is not my late father’s fault. It was the government that made it impossible for me, not him. But even knowing that, I still blamed my father. I just kept resenting him.

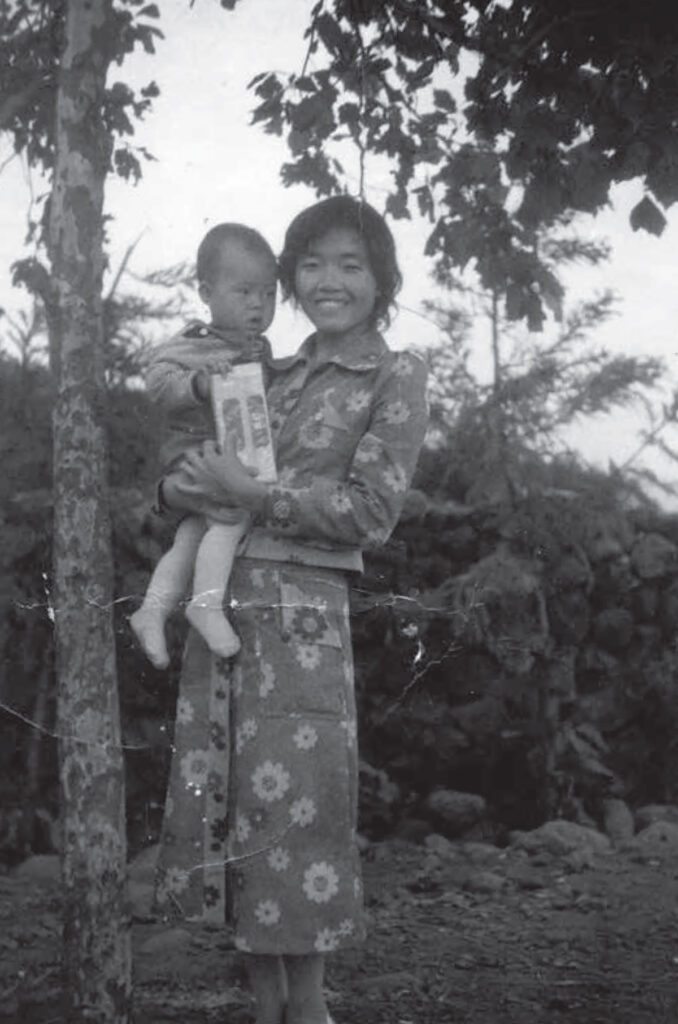

Kim Soon-ja in her 30s with her mother-in-law (left), her own mother (center), and her two sons

Marriage and standing on my own

When I couldn’t get the police appointment, I ended up getting married at 26. My husband was 27, a year older than me. He was also from Beophochon and was quite a respected figure in society. At one point, he held more than a dozen positions in Seogwipo. The problem was that while he was intelligent and admirable outside of the home, he became a complete tyrant at home. If anything didn’t go his way, he didn’t control his anger. By the time I turned 36 or 37, I was constantly visiting neurology and psychiatry clinics. I suffered from insomnia and ended up taking sleeping pills for over 30 years. I couldn’t take it anymore, so I left the house with nothing but my kids—not a single penny to my name. That was when my eldest son was in his first year of high school.

I had no house, no money, no rice—nothing. I felt completely helpless with my two sons. From that point on, I worked 19 hours a day. I washed dishes at restaurants, cleaned hotels, worked as a laborer on various farms, and even took on jobs like cemetery maintenance, which was considered men’s work. I even worked as a manager of a grocery store and a hotel. Raising two sons with nothing to my name meant I had to do every kind of work imaginable. Working 19 hours a day left no time to call or meet with relatives, friends, or anyone I knew. I completely cut off all contact with people. Over time, my depression only got worse.

“Go to the sea. Go to the mountains. Meet people.”

Once I was finally able to make a decent living, I started to reflect on myself. When I went to neurology and psychiatry consultations, the doctors and professors all said the same thing: Spend time in nature. So, I started waking up at 5 a.m. and hiking to Witseoreum or Yeongsil on Mt. Hallasan and walking through Seogwipo Natural Recreation Forest. After doing that for five or six months, I found myself smiling—something I hadn’t done in years—even while watching TV. After three years, I was laughing out loud and clapping my hands. Eventually, I even started approaching people first to strike up conversations. I changed so much—it was incredible.

Photos of excavated remains from Darangshi Cave, displayed at “The Sad Song of Darangshi Cave,” the 2002 Jeju 4·3 documentary exhibition at Sejong Gallery, Jeju City.

Facing the truth about my father’s death

About 20 years ago, I suppose, I went to a Jeju 4·3 photo exhibition at the Cultural and Arts Center. It was the first time I had ever attended a Jeju 4·3-related event, and it was truly shocking. The photos were so brutal, so horrifying. The people in the pictures looked so devastated that I thought, “This isn’t just any war—this is something far worse.”

“I spent my life blaming my father, who died so unfairly! Oh, what kind of terrible person does that? I’m not even worthy of being called his daughter!”

The exhibition hall was packed with people, but I just collapsed to the floor and cried out loud. I had no idea my father’s death had been so horrific. As a daughter who should have mourned her father’s unjust death, I had blamed him instead, my whole life. What kind of unfilial child does that? What kind of fool acts like that? I heard my father had died because of Jeju 4‧3, but I didn’t understand what it actually was. Before, after realizing that my father’s death during Jeju 4‧3 was the reason I couldn’t properly work as a teacher or get my police appointment, all I could think was, “Because of my father, all the hard work I put into my education was wasted.” I just resented him for it. I had no idea my father had been so brutally massacred. Now, I only feel sorry toward him. I’m sorry I didn’t understand the circumstances of his death.

Kim Soon-ja in her 20s with her eldest son

Speaking about the guilt-by-association system

If I had received the police appointment back then, I probably would have spent my life as a police officer. I’m Blood Type O and have a bit of a masculine personality, so I think I would have been good at it. If I had become a police officer, maybe my marriage would have turned out differently. I wouldn’t have had to do day labor, picking tangerines at one house and weeding at another, just to feed my family every day. Maybe I wouldn’t have gotten married in the first place if the police appointment had come through. If that had been the case, I wouldn’t have spent years going in and out of neurology and psychiatry clinics, suffering from depression. I wouldn’t have worked 19 hours a day trying to stand on my own. When I let my thoughts wander like this, tracing the memories, I always end up back on that day—the day I was told to give up because the police appointment wasn’t going to happen.

But I no longer blame my father. I understand now. I know that my father also died unjustly, that it wasn’t his fault. It wasn’t the fault of those who died due to Jeju 4·3. The blame lies with the laws that treated the victims of Jeju 4·3 as criminals and the guilt-by-association system. I understand that clearly now.

Now, I feel more guilt toward my father than resentment. And my heart aches even more for my mother, who couldn’t speak a word about my father’s death, not even to her children, for her entire life. She carried that heavy burden all alone until the day she passed away—too heavy a weight for one person to bear. Her husband’s death and the stigma of guilt-by-association passed down to her children were too much for anyone to endure. “Say nothing about it!” Even now, I can vividly hear my mother saying those words. Only now do I realize that those words weren’t just meant to soothe me—they were her own way of resigning herself and making a firm resolution to survive.

Kim Soon-ja participates in a horticultural therapy program at the Jeju 4‧3 Trauma Center