A woman with two names and three fathers

Kim Myeong-seon (born in 1935 in Donggwang, Andeok, now lives in Jeju-si)

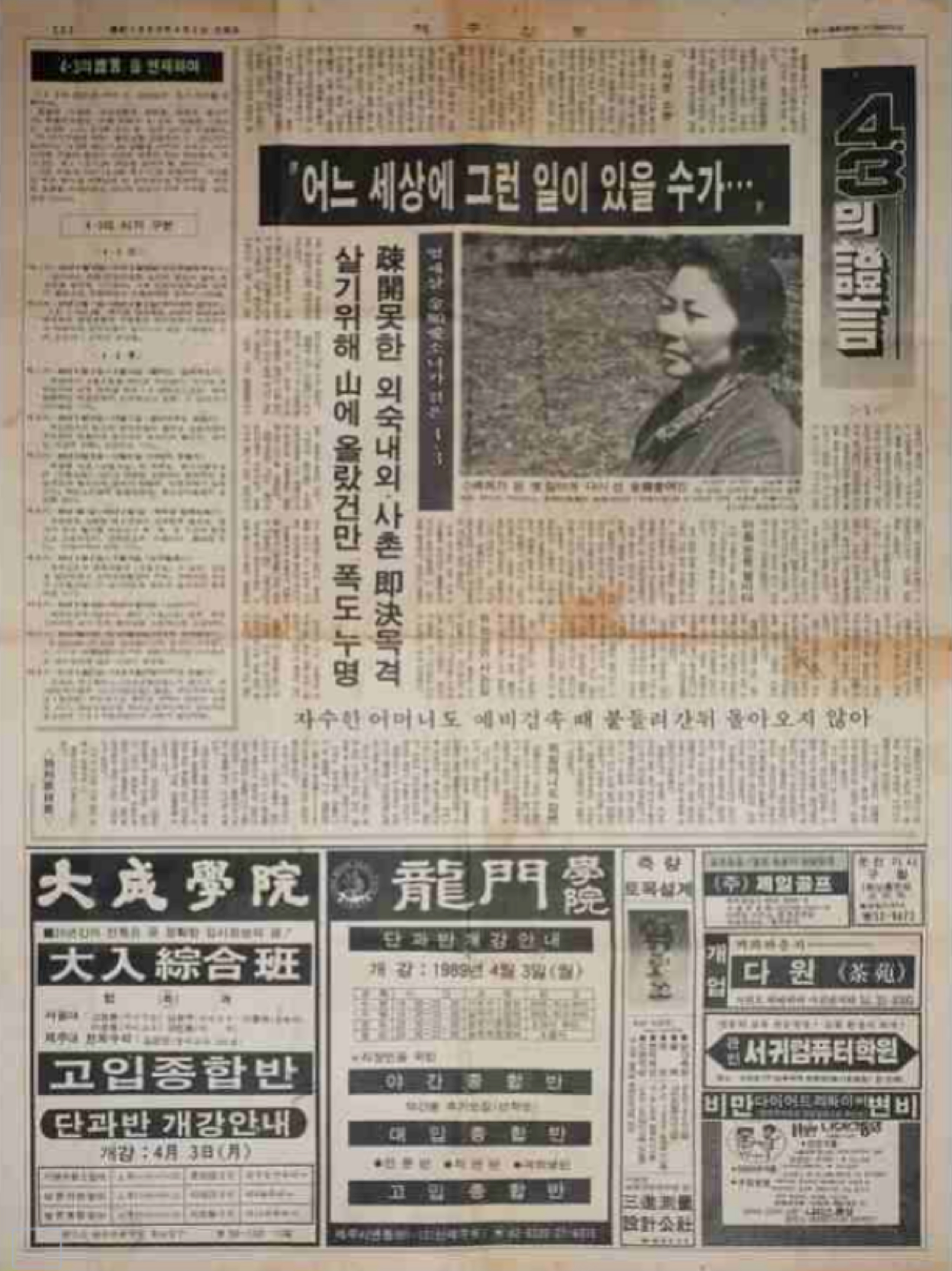

The first newspaper article about ‘Jeju 4·3 testimony’ released on JejuPress on April 3rd, 1989.

“How in the world could this be true…”

The first testimony on Jeju 4·3 to be released in a newspaper article on April 3rd, 1989, was the testimony of Kim, Myeong-seon who was 54 years old at the time. It was a tragedy she had experienced at the age of thirteen in Donggwang village. She barely had courage to speak out befire. It was in June 2021, only a few days before the closing date for ‘Notification of additional 4·3 victims and the bereaved families,’ that we met Kim, who is now 85 years old. She has had two names, three fathers, and a mother who was victimized and whose body is still yet to be recovered.

“How in the world could this be true?”

The story of Kim, Myeong-seon was not enough to be filled in on the document, which she wrote for the first time in her life. The interview reveals Myeong-seon’s life lived under another name, Kim, Soon-ae.

Photography/interview organized by Cho, Jeong-hee, Memorial Project Team of Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation

Long live, Myeong-seon

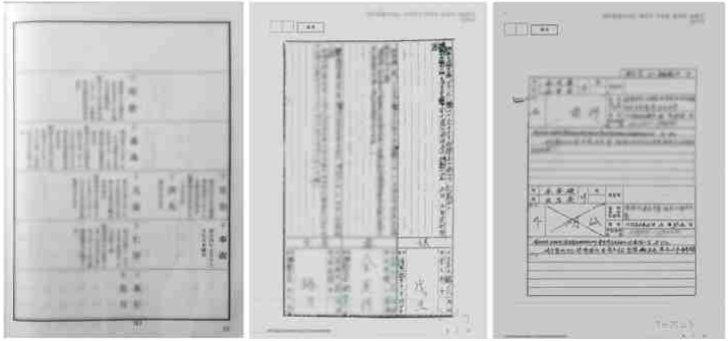

When I was young, I was called Soon-ae. Myeong-seon was a name in the register. My mother died when I was sixteen. After my mother’s death, I had nowhere to depend on, so I went all the way from Donggwang to Gimnyeong to look for my grandmother whose face I had barely remembered. That is when I put my other name on the register. The public record system was not thorough. My parents got married in Japan, and I doubt their marriage registration was properly transferred to Korea. So, I could not be registered as the daughter of my father. Instead, I had to be registered as a daughter of one of the uncles, Kim, Gyu-seok. This is how I became the youngest daughter of Kim, Gyu-seok and Lim, Chang-gyu, when, truly, I am the only daughter of my real mother Kang, Moo-saeng and my real father Kim, Bong-sook. Nevertheless, I could not do much in finding my true identity. I was young and there was no one who stood up for me. I had nowhere to depend on, and my life was miserable. By the way, my aunt’s name is Kim, Soon-yeo, which is similar to Soon-ae, my other name. My grandmother gave me another name, “Myeong-seon,” meaning a long life unlike the lives of my mother and father. The name was given to me after a shaman in Gimnyeong. Myeong (明) means brightness, and Seon (仙) means Taoist hermit who is believed to live a very long life. Normally, we do not use this Seon (仙) for a person’s name, but it is in my name. Perhaps this is why I live long enough today? On the other side, I miss my parents much. My parents knew me only as Soon-ae.

Family lineage and register of Kim, Bong-sook (father), Kang, Moo-saeng (mother), and Kim, Myeong-seon (daughter). The public records do not match to prove the family relationship between the parents and the daughter.

A present from my father

I was born in 1935 in Mudeungiwat, Donggwang-ri, Andeok-myeon. The place is where my mother is from. I do not know much about my father. All I know is that his name was Kim, Bong-sook, and that he is from Gimnyeong-ri, Gujwa-eup. From what my grandmother told me I know my father had assumed the leader of a group of people who lived in Japan. I heard that he passed away at sea later on. There seemed to have been a compensation for his death, but I do not know the details because it was not delivered to me. There was no one around me to tell me the story.

When my mother, carrying me within, came back to Jeju, she first went to Gimnyeong. However, her life with in-laws without the help of husband could not have been easy. Also, it was never easy for a woman from the mountainside region to adapt to the coastal region. So, she went back to her home, Mudeungiwat and gave birth to me. The news of my birth did eventually spread across the sea. There was one time when my grandmother visited my mother, with a congratulatory package from Japan that my father sent. It was a purple sweater. It was so beautiful, not just because it was the first and last thing my father ever presented me.

For ten years, my second father raised me

I learned all the numbers and letters from my mother. My mother was a teacher who taught children at night in Mudeungiwat. I studied together with the kids in the village for one winter. The next spring, my mother moved to Morokbat, Sangcheon-ri with me. There I saw Mr. Kim, Cheon-kwon, who I thought was my real father. It was because he was also a Kim, with the same family origin, Gimhae. He was very nice to me. I still remember when he taught me and my same-aged aunt a song. People also called him and my mother, ‘Soon-ae’s parents.’ So, I had to believe he was my real father. I did not know until we moved out from Morokbat again. I felt so frustrated and betrayed that I did not say hello to him when Cheon-kwon came all the way to Mudeungiwat to see me. Now I understand. My mother and Mr. Kim broke up because my mother could not bear a child. Cheon-kwon was the eldest son among eight of his brothers and sisters, so he needed children to keep on the family. But I cared little about it at the time. All I did care was the feeling that I have been tricked. However, Cheon-kwon raised me for 10 years as her own daughter. He was very sad that he could not meet me in person before going back, and it still pains my mind. I did not know it would be the last to see Kim, Cheon-kwon, because he died in Jeju 4·3.

Oh, the riots are people!

After I came back to Mudeungiwat, I went to school for the first time. There was no school in Morokbat. I was old enough to join the second grade. After two or three months, I saw adults gathered around. It seemed they captured a ‘riot.’ When I first heard the word ‘riot’ at the time, I became curious as to ‘what kind of animal is a riot?’ So, I and a bunch of students went to see what was going on. But, unlike my imagination, there was a man in a white cotton pants lying on a stretcher at the Mudeungiwat square. He was shot. That was when I thought, ‘Oh, the riots are people!’ Just when I thought they were some kind of animals like cats, I was surprised to see a man lying there. I was curious as to why they call him a riot when all I see is a man. I dared not to ask because I was more afraid of the people who brought in that ‘riot.’ They were young men with rifles, but I was more afraid of the U.S. soldiers. They were wearing yellowish uniform with red strips tied up on their hats. The soldiers were looking at us with such coldness. After that, there were occasions when a few American soldiers came to the village. Young women were afraid of them. That was the beginning of Jeju 4·3 in Mudeungiwat, the end of my school life, I should say.

Myeong-seon in her young days.

“This is going up the mountain, isn’t it!”

The time was around November in the same year. Adults were burying pots full of grains in the ground. Everyone was told to evacuate to the seaside or Hwasoon within three days. That was the so-called relocation. While those who had little to care took short enough to sort things out, people like my uncle, my mother’s brother, had a couple of houses, which was burdensome. The three-day limit passed, and the area came under martial law. Suddenly, trucks carrying police force with rifles rushed into Mudeungiwat. The men shouted,

“You’re going up the mountain with these goods!”

They did not wait for answer. ‘Bang!’ They shot indiscriminately at my uncle, who was loading luggage onto a carriage. ‘Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang!’ My uncle was a sturdy man. Somehow, he did not die at the first wave of bullets. He bent and rolled over here and there, in pain. “What is the meaning of this!” Shouted his wife. As she embraced her dying husband, there was a bang, and that was it. She was immediately shot dead in her head. I saw her falling right in front of me, but I still cannot believe it really happened. How can a fellow man do such a thing to another!

“This is going up the mountain, isn’t it! Don’t lie to me!”

They did not ask for answer this time, either. ‘Bang!’ The gunfire left my cousin dead. He was only twelve. They were coming after all of us. ‘Am I next?’ I felt the muzzles were pointing me and my cousin sister. My grandmother stood in front of us, like a wall. “Why are you doing this to our younglings!” She cried. With my grandmother and my mother begging for mercy, I held the hand of my cousin sister and ran towards the bamboo forest to the back of our house.

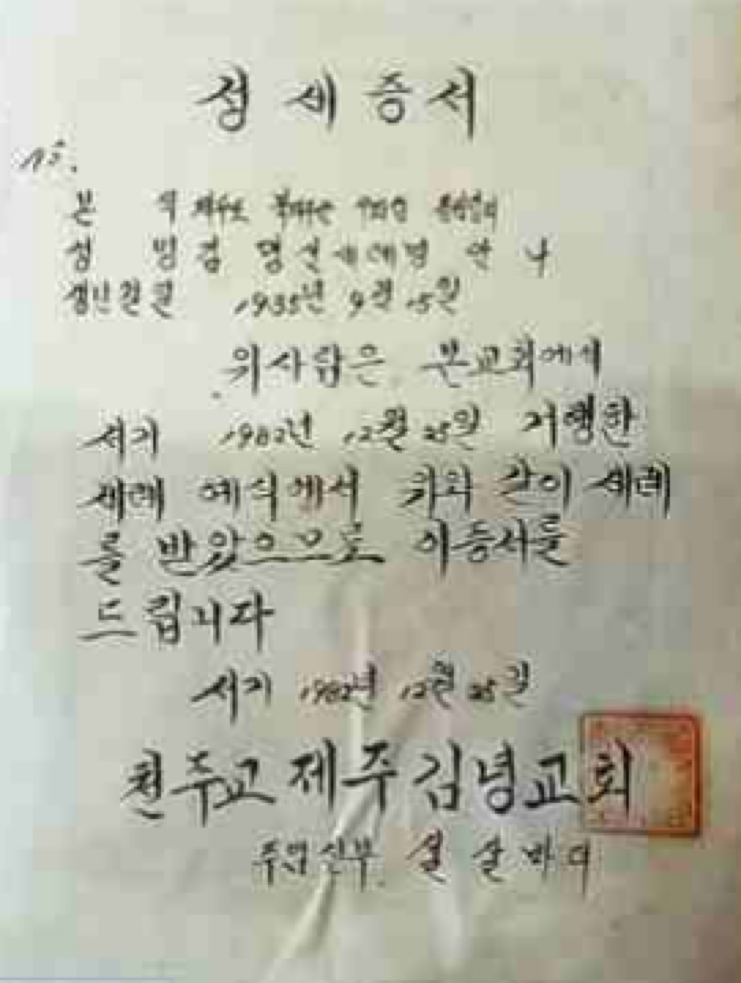

Myeong-seon’s baptismal certificate.

“It’s the girl! She’s running!”

The police force seemed like they were going to burn down everything, literally everything from houses, farms, people to every life including dogs and pigs that was in Mudeungiwat. After pillars of flame died down over the night, people who went hiding began coming out. Survivors helped me digging holes and burying my dead family. My uncle, aunt, and cousin brother were all buried dead. Then I left the village. Every little thing we carried out from the house burned. Not even a handful of rice remained. I had nothing left there.

I followed the survivors to a cave. There, we were barely holding out drinking drops of water. Eventually, the cave was also found by the police force. Everyone had to go their own ways. My dead uncle had four children, and the youngest one was barely old enough to walk. My grandmother had to take care of the young ones, while me and my mother followed villagers into the mountainside. As I heard the sounds of bullets ricocheting, we had to flee deeper into the mountain. When the police force shouted, “It’s a girl!”, I had to run as fast as I could without looking back. I was always a good runner and a skilled tree-climber. I never knew I’d be using the skill running about in the mountains for life. Anyway, I could see them running out of bullets while I was running from them. It was lucky we had no one who got shot. In the daytime, we sat under huge leaves of yew tree. Those spots were good for hiding from bullets. At night, we would boil millet and share its soup to stay warm. It was how we endured the winter. Sleeping was the most painful part. We had to lean on each other while crouching as we were sleeping. We were never able to stretch our legs while we were sleeping because doing so would wake others up.

There was one time when I said, “I just want to take a stride across a big road on a bright day and die.”

The hunger was severe, and my teeth ached. It seemed as if starving to death could be as painful as being shot to death.

Kim, Myeong-seon visiting Cheju (Jeju) Halla General Hospital last August to take a blood sample to find the remains of her missing mother.

Between the moments of ‘Ah, this is it!’ and ‘I am alive!’

The runners finally decided to turn themselves in and made a white flag with a white cloth and a broken wood. As we were coming down the mountain, armed police were waiting for us. The police shouted, “Hey! there comes today’s execution!” So, I thought, ‘Ah, this must be it!’ I could barely move by feet. After we arrived at Hwasoon Police Branch, they fed us with rice and seaweed soup. Now, the feeling of death turned to a relief, and I thought, ‘I am alive!’ Then, they had us get on a car. ‘Are we going to the execution?’ The feeling came back. At last, we were taken to a button factory in Seogwipo. There were many people, probably about two to three hundred. It was not easy to be fed well in such a crowded place. A pack of whole wheat cooked in a cauldron was never enough to feed that many people. All we had for one person was nearly two spoons of it. Salt was provided as the only side dish. People were famished and exhausted. Occasionally, we were let out of the factory building for a while, and people would chew any plant they saw in the field because they were so hungry. They grabbed anything they could eat from dead fish to fish eggs on the ground. Some who ate blowfish eggs died. That was when I learned things like blowfish eggs are lethal!

You eat to live another tearful day

After I was released from the button factory, I was sent back to Hwasoon. In Seogwipo, I could not even rent a room in Seogwipo because they called me a ‘riot.’ I found out that my grandmother was already executed by the police, not to mention my baby cousin brother who was with her. It is such a madness to call my 70-year-old grandmother and my baby cousin ‘riots.’ Time passed, and as I began caring the word ‘riot’ a bit less, the island came under another martial law. It was the Korean War. At dawn, the police rushed into my home and dragged my mother away. I felt, ‘This is the end!’

I just knew it. Later, I heard my mother was executed in Moseulpo under the Preliminary Inspection. I never got to see or recover her body. After I heard the death of my mother, I could not eat. For about half a month, I barely drank. If it had been for others, they would have gone sick or insane. After some time, I just wanted to live. So, I began eating again. You have to eat to shed tears. Can you feel what it was like?

Why are they being so mean to me?

There was a family where they said they wanted me as an adopted daughter. I went there, but it turned out what they wanted was a housemaid. Everyone around me was mean to me. They were trying to use me.

‘No, this is not what I wanted. I have to find my family!’

So, I went to Gimnyeong, my father’s home. However, the family at my father’s side was not that friendly to a grown-up sibling who was away for a long time. My grandmother held me with warmth not even one time. When I turned 20, I wanted to see my family back in Donggwang. I missed my mother and my cousins. So, I went to Donggwang and met my old cousin sister. When we were chattering cheerfully, an adult came by and suddenly hit me in my face, shouting, “You riot!”

He was the father of a police officer and had nothing to fear in the village. I was hit both my cheeks. My cousin sister was crying but I wasn’t. I did not shed a single tear. Why should I have been treated so? Why was everybody so mean to me?

My mother, left without her husband and without her daughter

It’s all in the past now. I learned no particular skills in my life. There were times, of course, when I did my best at work. I worked in a dying factory in Sanjicheon. For more than 10 years, I worked at a poultry farm in Gimnyeong. I did not earn much, but I am pretty satisfied with my life. I endured all the injustice well so far. Although I am alone, I did not feel loneliness. The Catholic church has been so much a strength for me. I was baptized in 1982, so, it has been almost 40 years since I entered the church.

There is one thing I feel bad about. It is about my mother. I am her only daughter, and I am not registered as one. Seeing my mother alone even after death. That is one thing that lingers in my mind. She does not have a tomb without her husband and her daughter. How lonely would that be? How sad would it be? This world could use some better idea for better things. How in the world could this be true?