The deaths of my family members and the five months I spent as a runaway

“Tell me who the real ‘rioters’ were!”

Hyeon Sang-ji (born in 1930; now lives in Nohyeong, Jeju)

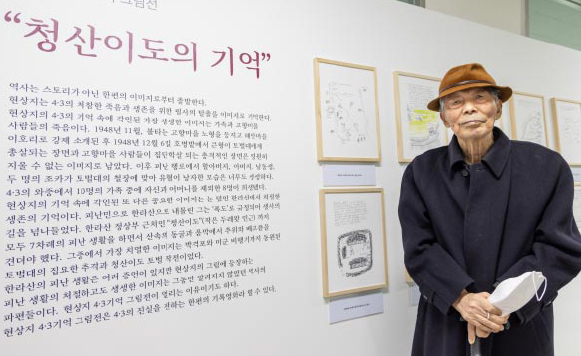

Hyeon Sang-ji gives testimony about Jeju 4·3 during the 14th Outreach Memorial Service, which performs Haewonsangsaeng gut [a spiritual ritual ceremony] in Nohyeong, held on April 9, 2016, Next to Hyeon is Cho Jeong-hee, head of the Memorial Project Team of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation.

On April 9, 2016, Hyeon Sang-ji gave the first testimony during the Haewonsangsaeng gut held in Nohyeong. He began by telling us he was just one of many who lived in silence, yet he still vividly remembered the painful day when eight of his family members were killed and how he cheated death on snow-covered Mount Halla as a runaway.

“Where should we go to live?”

In his reminiscence, his father asked the police who burnt down his house. There were numerous times Hyeon had to run just to be able to live another day. He was labeled a runaway, communist, rioter, and defector; on and on. In November 2021, at the Jeju 4·3 Trauma Healing Center, the Memorial Project Team met Hyeon again at the exhibition “Pictured Memories of Jeju 4·3 – The Memory of Cheongsanido.” The 91-year-old man still demands,

“Tell me who the real ‘rioters’ were!”

Arranged by Cho Jeong-hee of the Memorial Project Team

Drawings by Hyeon Sang-ji Photographs by Yang Dong-gyu, photographer

Hyeon Sang-ji gives testimony about Jeju 4·3 during the 14th Outreach Memorial Service, which performs Haewonsangsaeng gut [a spiritual ritual ceremony] in Nohyeong, held on April 9, 2016, Next to Hyeon is Cho Jeong-hee, head of the Memorial Project Team of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation.

What was Jeju 4·3?

I do not know what young people would think about Jeju 4·3 because they were not there. Well, I surely can say what it was. Soon after we were liberated from the duty of mandatory requisition during the Japanese occupation, everyone expected that the world was going to be a better place. I was fifteen then. Those who were older than me were delighted because they thought, ‘Hurray! We are safe from conscription, and now we will be able to hold communal rituals, too!’ But nothing really happened. Nothing truly changed.

“There will be no mandatory requisition. Nor will we starve after the liberation, will we?”

This is what everyone cared about. Not communism, nor democracy! We wanted to live with dignity and without starving! It was what Jeju 4·3 was about.

“I have no idea.”

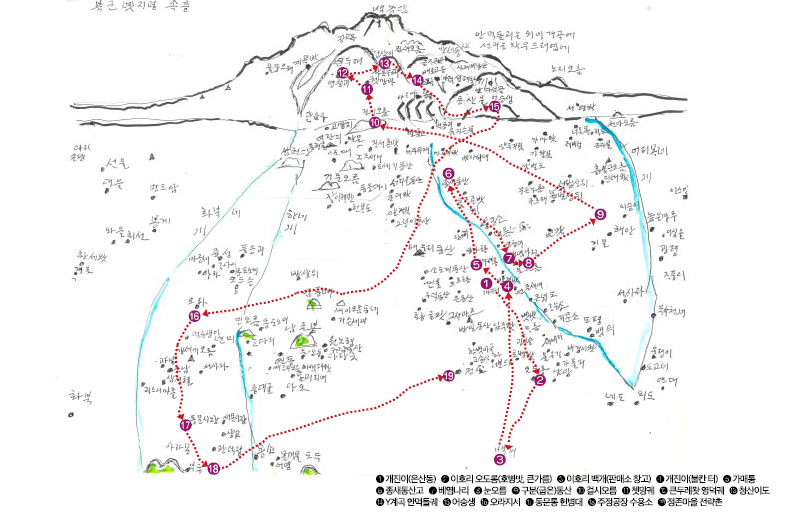

There is a famous hill in Nohyeong called Bangil Dongsan. When we were young, people called the place Na-pal Dongsan. About 500 meters south of the hill is Gaejini, or Eunsandong, the village I was born in and grew up in (Drawing ❶). In the summer of 1948, gunfire was heard from Bangil Dongsan. There was a skirmish, and it was said that a young man from Nohyeong was shot dead. After that, flags were placed up on the hilltop of Bangil Dongsan. When the flag was white, it meant ‘peace.’ If the flag went down, it meant ‘the police are coming up so be prepared for anything!’

“Where is your son?!” “I have no idea.”

The police rushed into our home and thrust their guns at my father. My second older brother, who had been helping my father, had seen the flag go down and was already hiding in a small, hidden cave under the stable. The police could not find my brother and were angry. They took me instead and tied me to a pine tree on the hill.

“Where is your brother!” “I do not know.” “Tell me or you will die!” “I don’t know!”

I was eighteen. Back then, I looked thirteen or fourteen years old because I was very short and skinny. Had I been a suspicious-looking boy I would not have survived that day. For some time, the flag kept going down on Bangil Dongsan. One day in early fall, the whole village of Nohyeong burned.

“Where should we go to live?” “Head to the shore!”

The inner and outer buildings, the stable, and the pigsty (toilet) all burned. At night, we roasted and ate the pigs. We buried the grain, or what was left of it, and went down to Odorong, Iho Village, which was nearest to Nohyeong (Drawing ❷), hoping we would get any food that we could there.

We barely made it and rented a small room just enough to fit the ten of us: our 82-year-old grandfather, 55-year-old father, 27-year-old eldest brother, 22-year-old second brother, myself; 18 years old, my mother, sister-in-law, my 12-year-old brother, and my 4-year-old and 2-year-old nephews.

“The young defectors are to report to Hobyeongbat to set up electric poles!”

After my eldest brother and second brother left, we heard gunfire. We did not know what happened. They said we were supposed to move to the coast if we were to live. My brothers never came back.

“Your older son was tied up and killed.”

The next day, there was another order. “Defectors are to head further towards the shore!” After my eldest brother died, and with the second brother’s whereabouts unknown, the remaining family moved to Keungareum in Iho Village. Days were becoming colder as it was the beginning of winter.

“Defectors are to assemble in the field in front of the shop!”

All whose houses were burned were to assemble, whether they were from Nohyeong or from Iho. Men, women, young and old crowded the field.

“Eyes shut!”

After a while, I opened my eyes. People were hung to wooden crosses in a field 50 meters away from the shop (Drawing ❸). Then, “Bang!” They were shot dead in front of us.

Back to ‘burned villages’ again

The days got colder, and rations ran low. Rumor had it that massacre awaited anyone who tried to flee.

“Let’s go back to our village and stay for maybe a week. There has got to be a way for us to survive.”

There was no other choice. There was no way the people of Iho Village would share their food with us, as we were known as defectors. With my second brother’s whereabouts unknown, we were already marked as fugitives. That night, our family of eight moved back to the burned village (Drawing ❹). We unearthed and carried the grain in a sack, and headed to Gamaetong, which was 2 kilometers away from home (Drawing ❺). We built a mud hut by the stream out of pine wood and spent two nights in the narrow hut. At dawn on the second day, we heard gunshots.

“You are surrounded. Turn yourselves in!”

Maybe it would have been better just to raise my hands and surrender. I did not think we would live anyway, but at the same time, I was reluctant to do as they demanded. I began running as fast as I could. I ran so fast that I forgot I left my family behind. I realized by the time I came to my senses that I had reached Jongsae Dongsan (Drawing ❻) in a short amount of time. The gunfire had ceased, and I had to find my family.

Beyeomnari, the place of my life’s regret

I reached Beyeomnari (Drawing ❼) to see people lying dead at the bottom of stream. They were mostly elderly. Those who couldn’t even walk without canes were caught and killed. There were dead elderly people who hid between rocks, too. The police kicked and shoved the captives off the cliff of Beyeomnari. No one survived the 5-6 meter fall. My grandfather and my father were found dead at the stream’s bottom as well.

“Mother, where were you hiding?”

My mother was busy preparing food for the family and could not run away in time. She told me that she crouched under a big rock at the bottom of the stream of Beyeomnari when the police came. They did not notice my mother was hiding under the very rock they were standing on.

‘I live, but…’

She was meant to live, but she could do nothing while her youngest son and daughter-in-law were being taken away with her grandsons on their backs. She couldn’t dare to show herself, nor had she the courage to beg for mercy. To my mother, what happened that day became the biggest sorrow of her life. We found my younger brother and nephews in Nun Oreum (Drawing ❽). The children were skewered, and my brother was barely alive with his intestines spilling out of his body. I carried him on my back and went back to the burned village, only to find that there was nothing I could do for him. I said goodbye to my brother in tears. Not knowing where my sister-in-law was, only my mother and I were left.

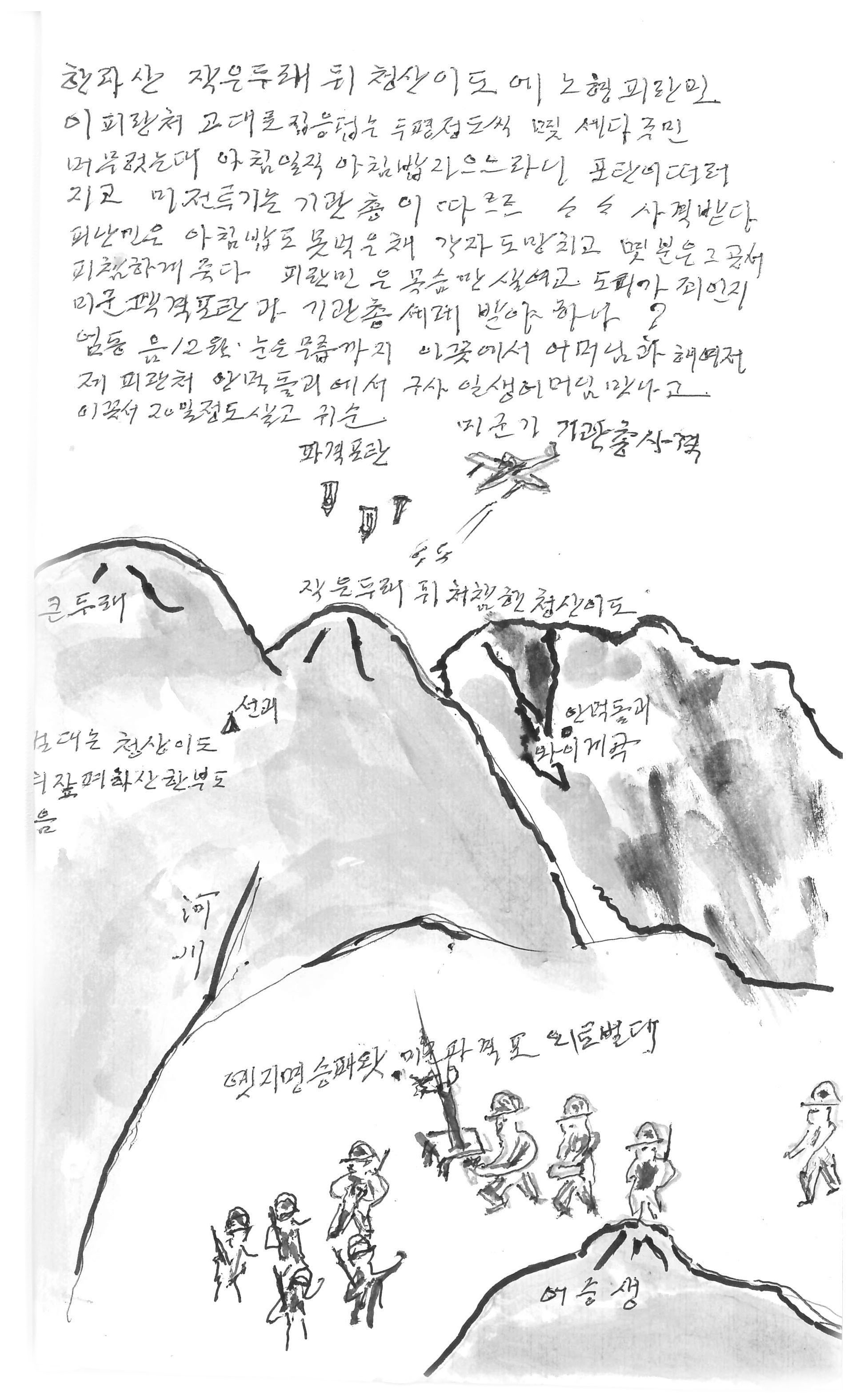

The subjugation of Cheongsanido on March 2, 1949 (February 3 on the lunar calendar). ‘Cheongsanido’ is a refuge located between Jogeundurewat and Keundurewat. There are two caves, one of which was a hideout for children, the elderly, and women. This cave suffered high casualties due to the police force’s concentrated attack.

Never have I felt that Hallasan was such a narrow place…

Now I was running away from the police.

Those who survived what happened in Gamaetong fled to Gubeun Dongsan (Drawing ❾) near a ranch at the coast. When they were found, they were chased down to Geolsi Oreum (Drawing ❿) and further south to Chetmanggwe (Drawing 11), and, again, as far as Yeongdeokgwe beneath Keundurewat (Drawing 12) and Cheongsanido, which is south of Jogeundurewat (Drawing 13). I stood watch on the top of Jogeundurewat. One day, I saw the police troops climbing up the hill near what is now Eorimok ticket office. The U.S. patrol reconnaissance planes were flying over, firing machine guns. There were mortar (high-angle gun) attacks launched by the police at Seungpaewat. We were like ‘mice in a trap.’ I began running again as fast as I could. I did not know where my mother went. The last shelter was Anmeokdolgwe (Drawing 14) near a Y-shaped valley in Hallasan. Not all of us could fit into the cave, so the refugees made a makeshift hut. There were young people who brought in the meat of wild horses from the field of Seopyeong to feed us refugees, but the food was never enough to ease our hunger.

“If you come down now, we will spare you unconditionally!”

It is what the pamphlets said, as they rained on us from the reconnaissance plane. There was nowhere left to run. Never have I felt Hallasan to be such a narrow place…. We were running out of food and had nowhere else to flee.

Hyeon Sang-ji’s mother (aged 72 in 1976).

Making a white flag to surrender

The young people who helped us were no more with us. We were on our own to live. I followed a handful of strangers to the top of Eoseungsaeng (Drawing 15). After holding on for some time, we decided to surrender and crafted white flags. As we were coming down the mountain to Jungjangnae, with our own white flags in our hands, we heard gunfire.

“You’re surrounded. Don’t move!”

We were caught by the police and taken to Ora police substation (Drawing 16). We spent a night and a day there and were sent to a military police office at Dongmontong (Drawing 17). The officer wearing a helmet picked out young people, and the rest were sent to a warehouse in a distillery (Drawing 18).

“How old are you?” “Sixteen.”

I was interrogated in that distillery for the first time in my life. I was eighteen, but I told them otherwise. I had to look younger to survive. Luckily, there were no more questions.

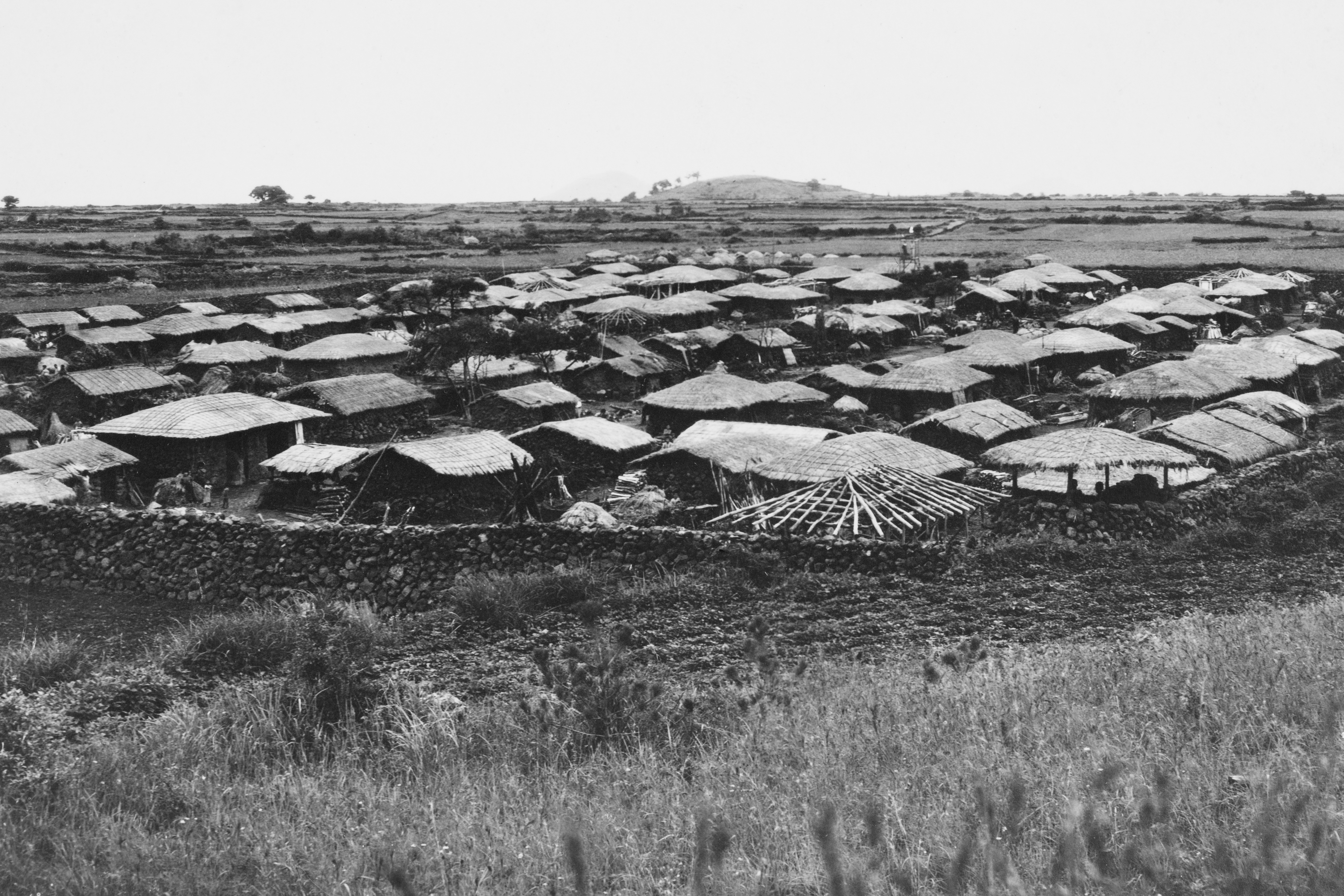

For what cause should I join the military?

I was reunited with my mother in the distillery. We were able to go back home together. Those who used to live in Nohyeong made a wall around what is now Nohyeong Elementary School (Jeongjon Village, Drawing 19). People lived in temporary buildings which were only 6 to 10 m2 wide per house. Then came the outbreak of the Korean War. I was conscripted and was to be sent to fight in the war. And for what?! They killed eight members of my family, and all that was left for me was my mother. I never wanted to leave. ‘For whom should I join the military? For what cause should I serve?’ I left for boot camp in Moseulpo in tears.

“Defectors are to come forward!”

In the Moseulpo camp, the training officer called out for defectors to identify themselves. I was frightened when they did. It turned out I had to make an ‘oath.’ To them, I was yet another ‘communist.’

This pictures shows the strategic hamlet of Nohyeong where villagers were accommodated during Jeju 4·3. People who used to live in Wollang, Gwangpyeong, Jeongjon, Wolsan, and Wonnohyeong Villages lived in their respective areas. Those who came down from the mountainside lived in the defectors’ zone.

Who were the real ‘rioters?’

Those who fled to the mountains during Jeju 4·3 were called rioters. Rioters refers to a group of people who are angry, violent, and mean. But never have I taken part in a riot nor gone near anything like it. The word would never fit my deeds. Now, you tell me who the real rioters were; who the relentless animals really were. The military, the police, and Northwest Korean Youth Association were, weren’t they? They were the rioters, and we were mere refugees who fled up the mountain. Why did we have to flee up the mountain? Because those rioters burnt all our homes and we were left with nowhere to return to. There was only one question we had.

“Where should we go to live?”

Seventy years of waiting

I thank the young people because they encouraged me to come here. After all, they weren’t there when Jeju 4·3 occurred. It is unfortunate that we, the older generations, were just too afraid to step forward. Back in the old days, it was never comfortable just to speak out. Now, the world is a much better place. I am grateful for that. However, we are far from closure even after the long wait. The young think the progress is going slowly, while victims and their families still think there is much more to be recovered and healed about the past.

“And so, the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park was built.”

It is a good thing, but the park is still a performative monument. It does not necessarily mean the victims are redeemed.

“We paid tax to build that park.” While many say so, politicians know that such a statement leaves pain in the hearts of us victims. This has to be settled now after all these years. We need closure. How many tears should we shed before it happens?”

Hyeon pays a visit to the exhibition, held by the Jeju 4·3 Trauma Healing Center.

I lost eight family members, and those who killed have never begged for forgiveness.

To be honest, I think the word ‘compensation’ is total nonsense. It is not compensation they have to give. The term is used when a solider is wounded or dies in war and the nation takes care of your family. Compensation is a kind of reward. But ‘reparation’ has a different meaning. It is a penalty imposed on the nation because it wreaked havoc on its people: all the killings and devastation of properties, to start with. Reparations are a fine. The government should offer us reparations and not compensation. Now they are bringing up the term compensation on the sly, which is cowardly behavior. This is not about the money. They say Korea is a developed nation with a mature democracy. Now it is time to ease the hearts of those who suffered. The victims and the families can forgive only if the apology is sincere enough to understand.