The investigation team named “Majungmul for National Unification through Jeju 4‧3” embarked on a journey to uncover the history of Jeju 4‧3 through the stories of those who ascended Mt. Hallasan. Since October 2017, its dedicated members have conducted 17 on-site investigations, culminating in the publication of two comprehensive reports. Just like the term Majungmul—the water that primes the pump—they aim to create foundational materials for future generations to build upon and utilize extensively. To learn more, we spoke with Bae Gi-cheol, the head of Majungmul’s investigative team.

The investigation team named “Majungmul for National Unification through Jeju 4‧3” embarked on a journey to uncover the history of Jeju 4‧3 through the stories of those who ascended Mt. Hallasan. Since October 2017, its dedicated members have conducted 17 on-site investigations, culminating in the publication of two comprehensive reports. Just like the term Majungmul—the water that primes the pump—they aim to create foundational materials for future generations to build upon and utilize extensively. To learn more, we spoke with Bae Gi-cheol, the head of Majungmul’s investigative team.

– Editor’s Note

Interview with Bae Gi-cheol, Head of Majungmul for National Unification through Jeju 4‧3

Interview and Compilation by Jang Yoon-sik, Head of Memorial Project Team, Jeju 4‧3 Peace Foundation

Bae Gi-cheol, head of the investigation team Majungmul, speaks with Jang Yoon-sik, director of the Memorial Project Team.

What led to the formation of the investigation team Majungmul?

What led to the formation of the investigation team Majungmul?

Majungmul began as a collective effort by individuals active in civic organizations in Jeju who wanted to engage in meaningful work for the region. For five years, I led a local civic group titled the Jeju Residents’ Autonomy Alliance. During that time, I noticed that past representatives or executive members of civic groups, farmers’ associations, and labor unions often disappeared from public life after serving for a couple of years and stepping down. This realization prompted me to approach former civic leaders and propose working together on initiatives that could benefit Jeju or engaging in meaningful work for the region. Together with those who agreed, we founded Majungmul.

In October 2015, we officially launched the investigation team. The full title is Majungmul for National Unification through Jeju 4‧3, and it’s currently led by Kang Dong-soo. We have 57 members divided into three subgroups. One focuses on investigating traces of armed resistance groups during Jeju 4‧3 in the dense forest areas stretching from Jeju Island’s mid-mountain regions to higher-altitude areas in Mt. Hallasan. Another is dedicated to investigating the traces of refugees. The members of the third engage in writing and reading. Beyond these core activities, we also support each other’s efforts and participate in regional events organized by other civic groups.

You’ve been conducting investigations for seven years. Could you elaborate on these activities?

There’s been significant research and fieldwork focused on the coastal and mid-mountain areas affected by Jeju 4‧3, while records about the alpine regions are scarce. During the Jeju 4‧3 period, many people sought refuge on Mt. Hallasan, either to escape persecution or for other purposes. There were opinions that documenting and organizing records about these people, as well as conducting investigations, were necessary to get closer to understanding the true nature of Jeju 4‧3. That’s why we began investigations on Mt. Hallasan, especially its dense forest areas.

Our fieldwork began in October 2017. Initially, we set a timeline of seven to eight years to thoroughly survey Jeju’s upland and forested areas. Tens of thousands of people fled to the mountain areas during Jeju 4‧3, and some voluntarily and intentionally ventured into the mountains to carry out their activities. It seemed like it would take about that amount of time to document their lives more thoroughly, so we set that as our goal. Starting two years ago, we began publishing reports on the subject. But now that it’s already the seventh year, we’re not sure if we’ll meet the planned goal. We’re just working hard to continue with the investigation.

Among our members, we gathered seven to eight people who could dedicate time to conducting investigations in the mountains. This group meets consistently and carries out the work. Every Sunday, we gather at a designated location, travel together, and conduct our investigations.

If I were to pinpoint the driving force behind seven years of investigative activities, I would say it’s the sense of pride and responsibility as Jeju residents. Everyone currently involved in these activities has been actively engaged in civil society work within the Jeju region. They are individuals with a strong desire to safeguard Jeju properly, and their deep sense of responsibility drives them to uncover the yet-to-be-revealed traces of Jeju 4‧3.

There are also others who provide support besides our members. In particular, Han Sang-bong, a Hallasan humanities researcher who has studied the mountain for decades, has been immensely helpful. His expertise in the names of places deep within the dense forest, navigating the paths, and analyzing historical remains has contributed significantly to our efforts.

01: Majungmul conducts a survey at Jangtaeko Crater on Noro Oreum.

02: Majungmul holds a memorial ritual before beginning their survey at the Sannaemul Battle Site on Barime Oreum.

You are focusing on investigating the historical remains of Jeju 4‧3 on Mt. Hallasan. What is the significance of these Jeju 4‧3 sites?

When we define Jeju 4‧3, we describe it as “an incident in which countless Jeju residents lost their lives during the armed conflicts and suppression processes between the armed resistance and the counterinsurgency forces, spanning from the March 1 shooting incident in 1947 to the lifting of the Hallasan entry ban in 1954.”

Many people from coastal villages fell victim, but particularly in the mid-mountain settlements, widespread destruction led to significant civilian casualties.

As I mentioned earlier, by the spring of 1949, over 20,000 people had taken refuge and were living on the slopes of Mt. Hallasan. Most of them were residents who hid to escape brutal massacres. However, among them were individuals who, under the banner of “Resistance against Oppression” and “No Unilateral Election and Separate Government,” took to the mountains following the signal fire on April 3. To truly uncover the meaning and nature of Jeju 4‧3 and conduct a proper investigation into its truth, shouldn’t we bring their lives into focus? That is why we are searching throughout Mt. Hallasan, focusing on aspects that have yet to be fully illuminated. Looking into the still-existing remnants, we aim to shed light on the lives of the Jeju residents during that time.

The traces of refugees and armed groups from that time help us investigate which areas they came from, which paths they used to ascend Mt. Hallasan, how they lived there, and the processes through which they were suppressed, killed, or captured. By analyzing the discovered remnants and artifacts, we can also infer the extent of the suppression in specific locations, such as by discerning, “This area must have experienced severe crackdowns.”

During Jeju 4‧3, there were over 2,100 missing victims in the Jeju region. It is estimated that many of them fell, nameless and unaccounted for, in the dense forests of Mt. Hallasan. Through our work, we hope that perhaps we might also uncover traces of those individuals.

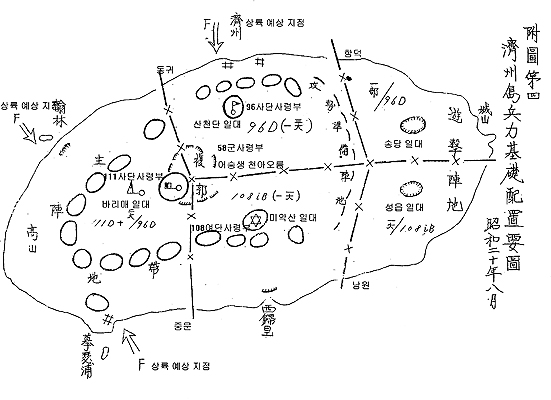

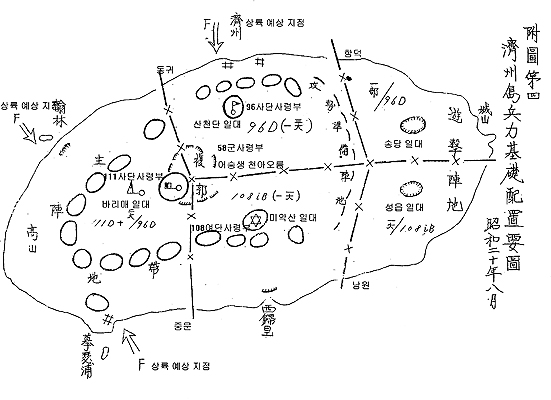

A Japanese military deployment map from the Japanese colonial period, used as a reference for the investigation

What areas have you investigated so far, and what have been the results?

Thus far, we have focused on areas such as Noro Oreum and Handae Oreum, both located in the mountainous regions of Aewol-eup, a northwestern village on Jeju Island. We also published a report in 2022.

The reason we started with Noro Oreum is that Kim Sok-pom’s novel Volcano Island features the Sanmulnae Battle between the counterinsurgency forces and the armed resistance. It also depicts the lives of refugees. Additionally, based on testimonies, many refugees from Aewol-myeon at the time were said to have fled toward Noro Oreum, which is why we began our investigation there.

From October 2017 to October 2022, Majungmul conducted investigations every Sunday, totaling 171 outings. Among these, 50 investigations focused on the Noro Oreum area. We explored in various directions, including Sannaemul, Jogeunbarimae, Ancheoni Oreum, and the Noro Oreum crater.

Once we began our investigations, we discovered far more traces than we had anticipated. In the case of Noro Oreum, not only in the Sanmulnae area which is a known battlefield, but also further north, there is a place colloquially called Deulgupgwe, where a stone cavern (“gwe”) is located beside a stream. Inside the cave, we uncovered numerous iron spears, brass spoons, and bullet casings. This confirmed that the area had been the site of a significant battle. Artifacts were found at varying distances, with M1 and Type 99 bullet casings being prevalent in the upper areas, while carbine bullet casings were more commonly discovered in the lower areas. Based on this, we speculate that there might have been a skirmish with the police counterinsurgency forces. Items such as abandoned iron spears and brass spoons seem to have been left behind during a retreat following the engagement. Near the summit of Noro Oreum, we also uncovered a large number of bullet casings at what appears to have been a guerrilla lookout post. This suggests that a major battle may have occurred near the summit as well. Additionally, in the crater of Noro Oreum, we found various artifacts, such as discarded ammunition boxes. We assume that refugees and armed resistance groups may have lived in this area for an extended period at the time.

To add for reference, the large crater of Noro Oreum is called “Jangtaeko.” Inside it, you can find remains of stone house foundations, dug-out shelters where huts were built, and clear traces of lookout posts. These features have been remarkably well preserved.

Handae Oreum is a mountainous area corresponding to San 1-beonji of Bongseong-ri and San 25-beonji of Eoeum-ri in Aewol-eup. It is said that many residents of Hallim-myeon sought refuge there during Jeju 4‧3. We conducted a total of 51 investigations, and the investigation report was published in December 2023.

Upon investigating the Handae Oreum area, we found that traces of refugees and armed groups from Jeju 4‧3 remain intact. Handae Oreum has many cave fortifications and trenches that the Japanese Army constructed during the Japanese colonial period, and there are signs that these were used for living during Jeju 4‧3. Additionally, to the south, there is a creek called Jonnaeteum that flows into Changgocheon Stream. Around this area, there are numerous stone caverns and remnants of slash-and-burn farmers’ living sites, providing evidence that people hid and lived there during the turmoil of Jeju 4‧3.

Additionally, to the west of Handae Oreum lies a wide wetland called Handaebeonji, where traces of a police counterinsurgency force’s base have been discovered, including bullet casings.

Particularly, the area around the ridge on the southwest side of Handae Oreum, which is called Handaebike, served as a major stronghold for refugees and armed resistance. In this area, we found numerous dugout hut sites, stone house foundations, and stone caverns. This is also where we uncovered many artifacts from the time, including household tools, weapons like iron spears, and evidence of battles.

01: Investigators examine the interior of a cave at Handae Oreum.

01: Investigators examine the interior of a cave at Handae Oreum.

02: A stone house foundation remains at Handae Oreum.

02: A stone house foundation remains at Handae Oreum.

03: A cave fortification for military purposes from the Japanese colonial period stands at Darae Oreum.

03: A cave fortification for military purposes from the Japanese colonial period stands at Darae Oreum.

A significant number of artifacts have been uncovered during your investigations. How do you handle these discovered items?

We use the observation equipment we have to document the locations, and most of the artifacts we identify are left onsite. We don’t collect them. Even if we brought them back, we would have no way to store them. So, we only bring back a very small portion, which we use for exhibitions to inform the public. Almost 99% of the items are left buried there. We purchased equipment like metal detectors by pooling contributions. Members voluntarily pay membership fees and even chip in for special equipment when needed, allowing us to proceed without major difficulties. In that sense, the members’ volunteerism and solidarity are remarkable. However, we face significant challenges in covering costs for writing reports after investigations or hosting larger events. For those, we’re exploring other means to secure the necessary funding.

Investigation team leader Bae Gi-cheol conducts a survey at Noro Oreum using a metal detector.

Investigation team leader Bae Gi-cheol conducts a survey at Noro Oreum using a metal detector.

Could you explain your future investigation plans?

We plan to investigate the mountain refuge areas of residents from all 12 regions of Jeju Island during Jeju 4‧3, including the bases of the armed resistance and the places where traces of battles remain. The first site was Noro Oreum, where residents of Aewol-myeon sought refuge. The second was Handae Oreum, where residents of Hallim-myeon fled. The next site has already been decided: the Dol Oreum area, where residents of Daejeong and Andeok sought refuge. Following this plan, we aim to circle around Jeju Island, investigating one or two areas per year.

This will be how we are investigating the mountainous areas close to mid-mountain villages, but what remains is the Hallasan National Park area. As suppression intensified at the time of Jeju 4‧3, residents were driven up to what is now Hallasan National Park, and naturally, the armed resistance groups were forced to move their bases deeper into Mt. Hallasan. Armed clashes with the counterinsurgency forces occurred in various locations. For these reasons, we plan to investigate the Hallasan National Park area.

Specifically, investigations need to be conducted in areas such as Eoseungsaengak Oreum and Yeongsil Oreum to the west; Beopjeongak Oreum and Bolle Oreum above Si Oreum to the southwest; Nonggoak above Solbat or Saloreum near Seongpanak Oreum to the southeast; and the surroundings of Muljangori Oreum near Gwaneumsa Temple to the east. By doing so, we can trace the routes of movement of Jeju residents from their nearby village shelters to the mid-mountain areas and, ultimately, deep into Mt. Hallasan. This will also allow us to identify the bases of the armed resistance and the battle zones. Connecting all these elements is essential for enhancing the completeness of the truth-finding efforts related to Jeju 4‧3.

The National Park area is challenging to navigate due to its rugged terrain. Despite this, we believe delaying the investigation too long will only make it harder. Members who are currently conducting the investigations often joke, half-seriously, “If we don’t finish the Hallasan investigation soon, it’ll be too difficult as we age.” This highlights the need for participation from younger generations, but unfortunately, that isn’t the reality. Another issue to resolve is that access to the Hallasan National Park is restricted. Entry isn’t permitted for just anyone. Therefore, we need to secure ongoing permits for accessing Jeju 4‧3 investigation sites and establish procedures to complete the investigations as quickly as possible.

Are there any particularly memorable sites or moments from your investigations so far?

The most memorable place is undoubtedly the Jangtaeko crater at Noro Oreum. When we first started investigating, the area was so overgrown with thickets and brambles that it was hard to see anything. But as we continued, we discovered remarkably clear traces of the guerrilla fighters and refugees who had been there at the time. There were lookout posts on both sides of the entrance to the crater, likely used for guarding the area. Inside, we found numerous dugout foundations for huts arranged all around, making it clear that a significant number of people had lived there. We also uncovered a surprising amount of artifacts, such as bowls and dishes used for daily life, as well as bullet casings and projectiles from battles. The site was so well-preserved that it left us astonished. To this day, it remains the most unforgettable part of our investigations.

Noro Oreum House Foundations

01: Aluminum bowl

02: Short-handled brass spoon

03: Scissors handle

Artifacts from Noro Oreum Crater (Jangtaeko)

04: Multiple M1 Garand bullet casings

05: Two M1 carbine casings and one M1 Garand projectile

06: Pickaxe head

07: Button

08: Northern summit lookout post

You must have faced many difficulties during your investigations.

Of course. The main challenge is that there aren’t many detailed testimonies related to the armed resistance groups or the refugees in the mountains. We visit various areas, listen to the testimonies of elders who are still alive, and try to pinpoint specific locations. However, most of the survivors were only teenagers at the time, so it’s often difficult to identify exact place names or precise locations.

That’s why we rely on various collections of testimony published through the efforts of many researchers who have studied Jeju 4‧3, such as Jeju 4‧3 Speaks and Now We Can Finally Speak. These records help us infer investigation sites. However, there aren’t many detailed testimonies about specific locations from that time, which makes it challenging. Looking back, I often wonder why those earlier testimonies lacked precise details about specific points or areas. It’s something that I now find deeply regrettable.

Even now, there are stories that so many people died at that time but their bodies were never recovered. Since the exact locations are unknown, it’s undoubtedly difficult to find them.

Still, we are making a great effort to piece together factual accounts by conducting repeated investigations and cross-referencing the existing testimonies with the areas we are exploring.

Another challenge is that our investigations are conducted in mountainous areas, where the terrain becomes particularly difficult to navigate after spring. During summer and fall, bamboo grass and thorn bushes grow so densely that cutting through them is a significant challenge. In the early days, I would sometimes go alone whenever I had time, but nowadays, I can’t do that because of the fear of stray dogs. On a few occasions, I encountered stray dogs while investigating, and one time I saw a pack hunting a roe deer. After witnessing that, I became too scared to go alone. There are also many snakes, wild boars, and other hazards, so safety concerns are always a major difficulty we face.

On the other hand, there must have been some rewarding moments as well.

The most rewarding moment was two years ago when we published our first report. No matter how much we investigate, it’s crucial to document and organize the findings so that future generations can use them as a foundation for more detailed and accurate research. We can’t achieve complete investigations ourselves, so we hope the groundwork we lay now will enable future generations to build on it and enrich the work further. When the first report was released, it felt like we had established a solid foundation for such efforts, and that was the moment I felt the greatest sense of accomplishment.

01: Artifacts are arranged for the exhibition during the 2022 Jeju 4‧3 Heritage Site Investigation Report Presentation held at the Jeju Provincial Council’s Citizen Café in December 2022.

01: Artifacts are arranged for the exhibition during the 2022 Jeju 4‧3 Heritage Site Investigation Report Presentation held at the Jeju Provincial Council’s Citizen Café in December 2022.

02: Excerpt from the Noro Oreum Investigation Report: Detailed Map of the Noro Oreum Area

02: Excerpt from the Noro Oreum Investigation Report: Detailed Map of the Noro Oreum Area

You’ve emphasized passing this down to future generations. Have you made any efforts in Majungmul to involve younger people in the investigations?

Of course. A Jeju 4‧3-related club was established at Jeju National University a couple of years ago, and it is still active. We’ve conducted investigations with the students from that club twice, guiding them through the areas we’ve explored and sharing the findings from our investigations. These joint field trips and discussions are part of an ongoing collaboration. We’re continuing to meet with them to pursue projects related to Jeju 4‧3, with the hope that these younger generations can build on our work and investigate areas that have yet to be explored. We believe it will be even better if we can continue working together, so we’re putting in a lot of effort to make this happen.

What does Jeju 4‧3 mean to Majungmul, and how do you think future challenges related to it should be addressed?

As the name Majungmul for National Unification through Jeju 4‧3 suggests, Jeju 4‧3 is not simply a skirmish between counterinsurgency forces and armed resistance or an event where innocent people were tragically killed after the signal fire was lit one day.

Jeju 4‧3 unfolded over a long period and carries multiple layers of meaning. There were those in the post-liberation era who aspired to establish an independent nation and those who sought to protect the Jeju community as a whole. Jeju 4‧3 can be seen as a resistance against the forces suppressing such aspirations, as well as the actions of those who opposed the South-side unilateral election and government formation and deliberately took to the mountains. At the same time, it includes the stories of refugees who fled to the mountains to escape indiscriminate massacres. I believe that bringing together and organizing all these narratives is crucial to clarifying the truth about Jeju 4‧3 and effectively addressing the challenges it presents.

Thus far, the efforts to uncover the truth about Jeju 4‧3 and address its associated issues have been driven by the dedication of Jeju residents. Significant progress has indeed been made, including advancements in matters such as state reparation and Family Relationship Register issues.

However, there are still many challenges to address moving forward. Reparation does not mark the end. There are still unexplored aspects, lives unaccounted for, and untold deaths that need to be acknowledged. I hope we can continue to work together to uncover these stories and make further progress.

Is there anything you hope for or expect from the Jeju 4‧3 Peace Foundation?

The Jeju 4‧3 Peace Foundation was established as a result of the efforts and achievements made in addressing Jeju 4‧3. I hope the foundation will serve as a central coordinating body that embraces and aligns the efforts of organizations related to Jeju 4‧3, both within Jeju and across the country and abroad, helping them move forward together on the path to resolution. Additionally, I hope it will actively support and empower the activities of individual organizations working on Jeju 4‧3-related issues.

Another thing is that during our investigations, we’ve found that the testimonies and other materials related to Jeju 4‧3 are incredibly vast. I hope the foundation will take the lead in organizing these resources effectively and creating an archive that is easily accessible to the public while also serving as valuable research material for scholars.

Currently, most of the Jeju 4‧3 historical sites consist of lost villages, counterinsurgency force bases, and massacre sites. I also hope that the traces of refugees and guerrilla fighters in the mountainous areas we are investigating will be well preserved as part of these historical sites. I would like the Jeju 4‧3 Peace Foundation to contribute to this effort as well.

Jeju 4‧3 Feature Film Screenplay Award Ceremony

Jeju 4‧3 Feature Film Screenplay Award Ceremony

The investigation team named “Majungmul for National Unification through Jeju 4‧3” embarked on a journey to uncover the history of Jeju 4‧3 through the stories of those who ascended Mt. Hallasan. Since October 2017, its dedicated members have conducted 17 on-site investigations, culminating in the publication of two comprehensive reports. Just like the term Majungmul—the water that primes the pump—they aim to create foundational materials for future generations to build upon and utilize extensively. To learn more, we spoke with Bae Gi-cheol, the head of Majungmul’s investigative team.

The investigation team named “Majungmul for National Unification through Jeju 4‧3” embarked on a journey to uncover the history of Jeju 4‧3 through the stories of those who ascended Mt. Hallasan. Since October 2017, its dedicated members have conducted 17 on-site investigations, culminating in the publication of two comprehensive reports. Just like the term Majungmul—the water that primes the pump—they aim to create foundational materials for future generations to build upon and utilize extensively. To learn more, we spoke with Bae Gi-cheol, the head of Majungmul’s investigative team. What led to the formation of the investigation team Majungmul?

What led to the formation of the investigation team Majungmul?

01: Investigators examine the interior of a cave at Handae Oreum.

01: Investigators examine the interior of a cave at Handae Oreum. 02: A stone house foundation remains at Handae Oreum.

02: A stone house foundation remains at Handae Oreum. 03: A cave fortification for military purposes from the Japanese colonial period stands at Darae Oreum.

03: A cave fortification for military purposes from the Japanese colonial period stands at Darae Oreum. Investigation team leader Bae Gi-cheol conducts a survey at Noro Oreum using a metal detector.

Investigation team leader Bae Gi-cheol conducts a survey at Noro Oreum using a metal detector.

01: Artifacts are arranged for the exhibition during the 2022 Jeju 4‧3 Heritage Site Investigation Report Presentation held at the Jeju Provincial Council’s Citizen Café in December 2022.

01: Artifacts are arranged for the exhibition during the 2022 Jeju 4‧3 Heritage Site Investigation Report Presentation held at the Jeju Provincial Council’s Citizen Café in December 2022. 02: Excerpt from the Noro Oreum Investigation Report: Detailed Map of the Noro Oreum Area

02: Excerpt from the Noro Oreum Investigation Report: Detailed Map of the Noro Oreum Area Two urns, wrapped in white cloth, were carried into the hall one at a time. Families, finally reunited with the remains of their loved ones after an arduous 76 years, gathered in solemn recognition.

Two urns, wrapped in white cloth, were carried into the hall one at a time. Families, finally reunited with the remains of their loved ones after an arduous 76 years, gathered in solemn recognition.

This poignant scene unfolded on Feb. 20, 2024, at the Jeju 4‧3 Peace Education Center during the Jeju 4‧3 Victim Remains Identification Report Session, organized by the Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, the Association for Bereaved Families of the Jeju 4‧3 Victims, and the Jeju 4‧3 Peace Foundation.

This poignant scene unfolded on Feb. 20, 2024, at the Jeju 4‧3 Peace Education Center during the Jeju 4‧3 Victim Remains Identification Report Session, organized by the Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, the Association for Bereaved Families of the Jeju 4‧3 Victims, and the Jeju 4‧3 Peace Foundation.

The other victim, the late Lee Han-seong (born in 1923), was a resident of Hwabuk-ri in Jeju-eup, a village in the northern part of Jeju Island. Lee was sentenced to death by a court-martial in 1949 and subsequently disappeared. During Jeju 4‧3, the Hwabuk-ri resident fled from the oppressive Northwest Youth League members. Lured by a constabulary leaflet distributed in June 1949 that promised safety in return for surrender, he turned himself in at Hwabuk Elementary School, where police forces were stationed. Contrary to assurances, however, the court-martial sentenced him to death on June 28, 1949. He and dozens of others were reportedly loaded onto trucks and taken toward Jeju Airport, after which they vanished. Lee’s mother and younger sister were also killed simply because they were his family. His elder brother, Lee Han-bin, also disappeared after being taken to a prison on the Korean mainland.

The other victim, the late Lee Han-seong (born in 1923), was a resident of Hwabuk-ri in Jeju-eup, a village in the northern part of Jeju Island. Lee was sentenced to death by a court-martial in 1949 and subsequently disappeared. During Jeju 4‧3, the Hwabuk-ri resident fled from the oppressive Northwest Youth League members. Lured by a constabulary leaflet distributed in June 1949 that promised safety in return for surrender, he turned himself in at Hwabuk Elementary School, where police forces were stationed. Contrary to assurances, however, the court-martial sentenced him to death on June 28, 1949. He and dozens of others were reportedly loaded onto trucks and taken toward Jeju Airport, after which they vanished. Lee’s mother and younger sister were also killed simply because they were his family. His elder brother, Lee Han-bin, also disappeared after being taken to a prison on the Korean mainland. The victim’s younger brother, Lee Han-jin, is the president of the Association of Jeju People in America (New York) who has actively worked to raise international awareness of the Jeju 4‧3 atrocities. Traveling with his family from the United States, he attended the conference to reunite with his brother, whose remains were finally identified.

The victim’s younger brother, Lee Han-jin, is the president of the Association of Jeju People in America (New York) who has actively worked to raise international awareness of the Jeju 4‧3 atrocities. Traveling with his family from the United States, he attended the conference to reunite with his brother, whose remains were finally identified.