“Investigation, Collection, and Studies of Documents are the Key to Education on Jeju 4·3”

Cho Sung-youn

Cho Sung-youn, a professor emeritus of Sociology at Jeju National University, was born in Seoul in 1954. Cho received his master’s and doctoral degrees in sociology from Yonsei University and joined the Department of Sociology at Jeju National University in 1985. At the university, he served as the Director of the Tamla Culture Research Institute, the Director of the Institute of Peace Studies, and the head of the Department of Sociology at the Humanities College. His other former titles include a co-representative of the Jeju Participatory Environmental Network and a board member of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute, the Korean Sociological Association, and the Korean Academy of New Religions. Cho authored Soka Gakkai and Koreans Residing in Japan, The South Sea Islands: Occupation of Pacific Islands and Frustration by Imperial Japan, Koreans in the South Pacific Islands, and 1964: A Story of a Religion; co-authored Structure and Change of the Folk Beliefs in Jeju Island, The Stolen Period and the Stolen Times: A Story of the Jeju People, A Gift of Fatalistic Transition: A Story of the Korean Japanese Who Joined Soka Gakkai; and edited A Study on the Japanese Army on Jeju Island at the End of the Japanese Colonial Era and A Life on a South Pacific Island: A Memoire of a Korean Surnamed Matsumoto. The professor retired from teaching in February 2020 and is currently preparing articles on the memory of war and peace education, with the topics of the memory of the Battle of Okinawa, the South Pacific Islands, and the peace campaigns staged by Japan’s new religions.

The Jeju 4·3 Archive Exhibition: Traces That Became a Document” is being held in the Special Exhibition Room on the 2nd floor of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation. The archived show exhibits the documents, photos, books, video images, and news articles collected and held by the foundation, which were produced during Jeju 4∙3 or the process of uncovering the truth of the tragedy. Unfortunately, however, most of the Jeju 4∙3-related materials were destined to fail to exist despite the proud history of the historical event. This is because both the perpetrators of the massacres and the victims and their families had to burn even the last remaining piece of evidence to ash, the former trying to conceal their crime and the latter trying to avoid the false accusation of being communists. Given the scarcity of the documents, the original copy of The Written Decision on March 1 Protest (March 1 Statement) draws more attention. The March 1 Statement was distributed on March 1, 1947, during the ceremony commemorating the Samil (March 1) Independence Movement. The document is valuable in that it represents the starting point of Jeju 4·3 and the important points in history that determined the destinies of Jeju residents. I interviewed Cho Sung-youn, a professor emeritus of Sociology at Jeju National University, who donated the document to the foundation. – Editor –

Interview and arrangement by Cho Jung-hee, head of the Research and Investigation Team

Photography by Kim Yeong-mo, member of the Memorial Project Team

Cho Sung-youn visits Jeju 4·3 Archive Exhibition “Traces that became a document” held by the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation. Cho looks at The Jeju Resistance containing the materials he donated.

Cho Sung-youn visits Jeju 4·3 Archive Exhibition “Traces that became a document” held by the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation. Cho looks at The Jeju Resistance containing the materials he donated.

It is officially known that Jeju 4·3 began with the March 1 Incident of 1947. This seems to make your donation more significant.

I remember it was in 1986. I used to tell my students in my lectures: “You may have old documents in your house, such as your family relations register. As elderly people may not know what they are, don’t hand them over to street vendors or throw them away but keep them as your household documents.” One day, a student who kept it in mind brought to me a package of documents he had found at home. He was a student living in Samyang Village. He said that when he tore the roof off to repair the house, the package fell from the roof rafter! Looking at the package, I found some 4·3-related documents, such as the first draft of the South Korea Labor Party (SKLP) Code of Conduct, the March 1 Statement, and the minutes of preparatory meetings of the March 1 commemorative event. “These are historically important documents. Take them home and make sure you keep them carefully.” After listening to my explanation and suggestion, the student responded, “Prof. Cho, I can’t take the package back home because my father told me to take it away. I would like you to take it and decide what to do.” It was a time when people were not allowed to freely speak of Jeju 4·3, so I ended up just keeping it for several years. Then in 1990, I joined the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute as a board member. And I showed the documents to Hong Man-ki, the institute’s then Secretary-General. “Dr. Cho, will you just keep them for yourself?” To Hong’s question, I answered, “No, let’s open them to everyone.” Soon after we reached an agreement, the Secretary-General copied the text from the hard copy document by typing. Yang Han-kwon, a researcher who wrote papers on Jeju 4·3, took responsibility for annotations, while I reviewed and edited their works. That’s how the written copies were included in The Jeju Resistance, which is a book of Jeju 4·3-related documents published in 1991 by the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute. At the time, I expected that putting them in a book would be beneficial for the study of Jeju 4·3 because there was an influx of new researchers into the field, especially led by the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute. Honestly, it appeared that research on the SKLP would progress quickly. However, 30 years have passed since the release of The Jeju Resistance, and no researcher has studied the SKLP’s organization, other than Yang Jeong-shim, the head of the institute’s Investigation and Research Office, and Park Chan-shik, the institute’s former director. It is frustrating that the topic has not been studied more actively. Therefore, I recently decided to donate the entire original materials to the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation. Since the book has not been broadly used for reference, I wanted to propose another way to researchers. I expect the foundation to publicly post each page of the materials online so that anyone can easily access and view the documents. It is a good idea to have a special exhibition in the Jeju 4·3 Memorial Hall as is now, but another good way would be to open them online so that more people can see and use them, especially given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Cho Jeong-hee, the head of the Commemorative Project Team, interviews Prof. Cho Sung-youn.

Cho Jeong-hee, the head of the Commemorative Project Team, interviews Prof. Cho Sung-youn.

Could you tell us about the most memorable document related to Jeju 4·3 you studied or collected?

It is the most regrettable that I failed to have Lee Woon-bang’s handwritten manuscript be published. One day in 1995, Kim Chang-hoo, the director of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute, came to the office with a copy of Lee’s handwritten manuscript. We had a discussion and agreed to have the institute publish it as a book. I was in charge of organizing the manuscript. As I happened to go to the United States for research, I completed the work by typing while staying there. My plan was to publish a book in consultation with the author after my return to Korea. In February the following year, I received a phone call from the institute, asking for the typewritten manuscript because the institute had decided to publish Lee’s book soon. When I said, “We need to seek Lee’s approval first,” the institute’s researchers wanted to solve the issue by themselves. I sent the typewritten manuscript to them as they had requested. However, it turned out that they printed the book without finishing consulting with the author. From what I heard later, Lee had gotten angry because the institute edited his manuscript on its own. He said, “The manuscript is not exactly what I wrote.” Seeing the author express his anger, the institute had no choice but to discard all of the printed copies. Lee’s writing is so old-fashioned that it is very difficult to read. While typewriting his manuscript, I made minor changes to his sentences to make it easier to read. Although his keynote was not altered at all, the author regarded it as nothing better than a revision of his manuscript without his approval. We should have explained first as much as we could and asked for his understanding in advance. It was very disappointing that we had failed to do that. I tried to visit and talk to Lee after returning from the United States, but there was no way to solve the issue because he refused to see me. It was completely our fault. However long it would take, we should have persuaded Lee to publish the book, and further, we should have listened to him tell his life story and arranged his oral statement. Now that he passed away, we can no longer read or listen to any stories describing the situation around Jeju 4·3.

Although you are not from Jeju and taught at the university, you have been deeply involved in the so-called 4·3 bloc since the early 1990s. Any particular event that sparked your interest in the issue?

In 1981, when I was studying for a master’s degree, Japan’s Kokushokankokai Inc. (National Book Publishing) donated more than 100 books to the Institute of Korean Studies at Yonsei University. While I was organizing the books at the institute, Kim Bong-hyeon’s Bloody History of Jeju Island stood out. I thought to myself, “Bloody History? Why is the title so dreadful?” At first, it was simply because I was curious about it. I picked it up but it wasn’t easy to read because I wasn’t fluent at Japanese back then. Thinking that I would take time in reading it later, I left it at a copy place in front of my school for a photocopy. When I visited the shop again a few days later, the owner called somewhere. I got caught by an agent of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency, who was in charge of Yonsei University. We met in a coffee shop near my school. When asked why I asked the shop to create a photocopy of the book, I honestly replied that the title “Bloody History” sounded so unusual and gruesome. I said that although I was unable to read it soon because of my little knowledge of Japanese, I asked for its photocopy, thinking I would read it someday. I was able to avoid punishment thanks to my statement that I didn’t know what it was about because of my lowest ability to use the Japanese. It was a close call. However, that incident was an opportunity for me to open my eyes on the Jeju 4·3 issues.

After getting my master’s, I decided to study further to get a PhD. Soon after joining the PhD program, I started giving lectures at Gyeongsang National University and Chonbuk national University. I was thinking of studying the Donghak Peasant Revolution for my doctoral dissertation, but I was soon hired as a full-time lecturer by Jeju National University. So, it occurred to me that I could give up my interest in the Donghak Pheasant Revolution and, instead, change my research topic to the one about the history of Jeju Island. For several years from the first semester of 1985, the subject I gave as a final assignment to my students taking Introduction to Sociology was “Social Change on Jeju Island and My Family History”. I instructed my students to listen to their grandparents tell the stories of their family and write the history of their respective families. I used to have about 120 students in the Introduction to Sociology, and two-thirds of them wrote about Jeju 4·3. The students’ grandparents were giving testimonies about Jeju 4·3, as if it had been agreed upon in advance. It came as a complete shock to me. Their testimony of Jeju 4·3 was extended to the stories of stowaways to Japan and those who settled there as Korean Japanese people. I said to myself, “Oh! This is Jeju Island!” That’s how I learned about Jeju 4·3.

To my knowledge, you used to lead peace education at the university, especially with a focus on Jeju 4·3. Now that you are retired, what are your thoughts and feelings about teaching students about Jeju 4·3?

Shortly after the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute was established in 1989, the institute’s inaugural member named Ko Chang-hoon asked me to join its Board of Directors. The inaugural members needed other researchers to join them, but most of all, he said they needed additional members who would pay a monthly membership fee of 30,000 won and help with the management of the institute. That’s how I became a board member. However, I had the idea that the director, representing the institute, must be a researcher from Jeju Island. Since the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute was not only a research group but also a group committed to social movements, it was necessary to actually meet the victims’ bereaved families in person. Rather than focusing on the activities of the institute, I spent more time engaging in civic groups and peace education with the topic of Jeju 4·3 at universities. This year marks the 73rd anniversary of Jeju 4·3. Elementary, middle, and high schools seem to show significant changes, while I don’t feel any big difference in colleges. With the 70th anniversary as an opportunity, a growing number of teachers have shown particular interest in 4·3 and worked hard to teach it to young students. But colleges, especially Jeju National University, are so behind the latest move that a professor who specializes in studying the Jeju 4·3 issues was only recently appointed. Of course, it is fortunate that lectures on Jeju 4·3 have been offered to a certain degree in the undergraduate and graduate schools. But I think more changes have to be made in the near future. What would be the reason for the slow move towards change in the education sphere, despite our hard work to resolve the Jeju 4·3 issues? This is because the Jeju 4·3 bloc has not shown much interest in teaching the kids about Jeju 4·3 and has not seriously considered how to systematically educate them. We have indeed concentrated our attention on enacting and revising the Jeju 4·3 Special Act, developing a state-published report on the investigation of the truth of Jeju 4·3, establishing the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park, and holding various commemorative events. “How could we properly teach the coming generations about Jeju 4·3 and pass the lessons to be learned from Jeju 4·3 on to them?” The time has come to systematically plan the educational system concerning Jeju 4·3.

What should we do to properly teach students about Jeju 4·3?

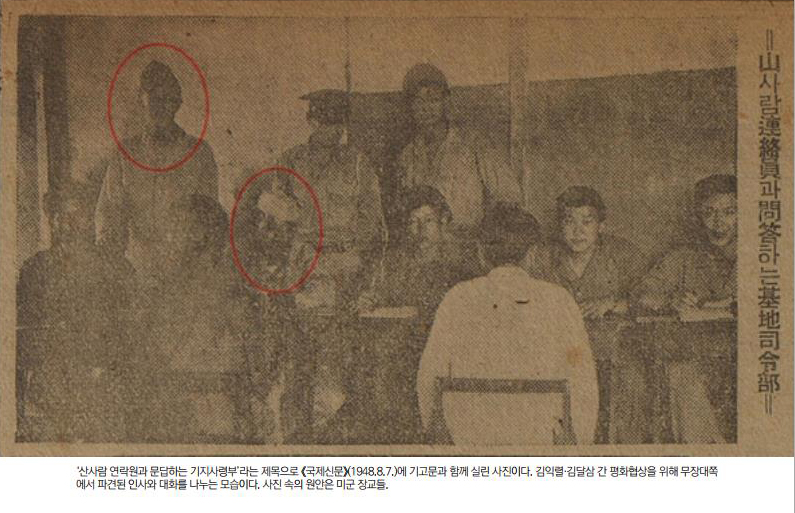

It’s very difficult to answer, but I think the investigation and research of Jeju 4·3 should be the priority. For this, it is most urgently needed to accurately provide data on Jeju 4·3 to researchers. It is important to investigate and collect the Jeju 4·3-related documents, such as the data held by the United States National Archives and Records Administration and the newspaper articles released during Jeju 4·3, as has been conducted by the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation. It needs to be done more systematically and continuously. The second is that we have collected the testimonials spoken by thousands of people who had experienced Jeju 4·3 in various institutions, organizations, and media. Are these testimonies being used properly for research purposes now? We need to have a system that can utilize the Jeju 4·3-related oral testimonials for research. The results of these two tasks should be archived and made available online. Based on this, both research and education will advance. From then on, the role of researchers becomes important. Different types of literature and testimonials related to Jeju 4·3 should be analyzed to derive various research findings. Furthermore, books and contents in diverse formats and types should be provided so that students and the public can easily understand them. And there, education on Jeju 4·3 takes place. We need to draw a comprehensive picture of investigation, research, and education.

Frankly, investigating and collecting data on Jeju 4·3 seems to be plausible to some extent if it is accompanied by a systematic plan and budget. However, isn’t it true that there have been voices for a long time that there is a shortage of 4·3 researchers?

What I really wanted to do when I was teaching in college was the Jeju 4·3 Researcher Incubation Project. I have had the question of how to foster graduate students, that is, master’s and doctoral students, as Jeju 4·3 researchers. So, I planned a three-year project that selects three students from among domestic and foreign graduate students each year to join the Jeju 4·3 Scholarship program. The students would receive a scholarship of 1 million won every month and would be required to write one article about Jeju 4·3 every semester. And their articles would be collected and published as a report on their research findings. Not only Jeju students, but also those students on the Korean mainland and in Japan, America, and Europe, would be invited to study together. Let’s say you have selected 30 students who will research Jeju 4·3 during their master’s or doctoral courses. Honestly, if only 10 of them grew to be Jeju 4·3 researchers, wouldn’t it be successful? If the project has been run for about 10 years and more researchers have joined the field of studying Jeju 4·3, wouldn’t it be possible to accumulate various research findings? And wouldn’t it naturally make it possible to realize the recognition of Jeju 4·3 on national and global scales? I used to have such expectations, although it ended as a plan in the end. Fortunately, however, the revised Jeju 4·3 Special Act allows the ensuing investigation into the Jeju 4·3 issues. If an investigation team is set up to conduct intensive investigations and research on Jeju 4·3 for several years, wouldn’t it be possible to naturally nurture new researchers in the process?

As you mentioned, with the amendment bill effective, the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation is to conduct additional investigations of the truth of Jeju 4·3. Any suggestions for us?

In 1993, the Jeju Provincial Council formed the 4·3 Special Committee and received damage claims caused due to Jeju 4·3. At the time, I was an advisor to the 4·3 Special Committee. An advisory committee meeting was held to collect claims for damage and develop a report, and that was the first time I was shocked. Some of the claims were made for the damage that the perpetrators of massacres had suffered, but most of the advisors wanted to delete those claims before releasing the report. Only two advisors including me raised the question, “Why are you taking out the perpetrators’ damage?” The rest of the advisory members said, “If you put it in now, it will cause a lot of trouble.” In the end, the report came out, with the claims concerning the damage on the perpetrators’ side completely. I lamented, “Oh! It is still difficult to resolve the Jeju 4·3 issues!” However, even when the Jeju 4·3 Special Act was first enacted in 2000, the focus remained only on the victims. Again, I deplored, “Oh! It has not changed at all!” And then, another 20 years have passed. Now, we have to draw the full image of Jeju 4·3, be it the damage caused to the victims or the damage the victimizers had suffered. Just because it is inconvenient to talk about it, we cannot just emphasize the one-sided damage, without identifying the perpetrators on both sides or investigating the activities of the armed guerilla forces. Only then will the legitimate name and historical evaluation of Jeju 4·3 be achieved.

A rally for Jeju residents was held at Gwandeokjeong Square on March 5, 2021, welcoming the passing of the motion on the general amendment of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act.

A rally for Jeju residents was held at Gwandeokjeong Square on March 5, 2021, welcoming the passing of the motion on the general amendment of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act. On March 16, the Jeju District Court held the final retrial process concerning Jeju 4·3 convicts, who had to serve jail terms under false accusations due to unlawful courts-martial. The Association of the Bereaved Families of the Jeju 4·3 Victims, including the Jeju 4·3 convicts who had applied for their retrial, are gathered in front of the district court to chant hurrahs after the court’s judgement on the acquittal of the victims’ false charges was announced.

On March 16, the Jeju District Court held the final retrial process concerning Jeju 4·3 convicts, who had to serve jail terms under false accusations due to unlawful courts-martial. The Association of the Bereaved Families of the Jeju 4·3 Victims, including the Jeju 4·3 convicts who had applied for their retrial, are gathered in front of the district court to chant hurrahs after the court’s judgement on the acquittal of the victims’ false charges was announced. On the rainy day of the 73rd Memorial Ceremony for the Victims of Jeju 4·3, a victim’s family member visits the Headstone Monument Engraved with the Names of the Victims in the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park to pray for rest of the victims.

On the rainy day of the 73rd Memorial Ceremony for the Victims of Jeju 4·3, a victim’s family member visits the Headstone Monument Engraved with the Names of the Victims in the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park to pray for rest of the victims.