Resolution of Jeju 4·3: Achievements and Contributions

A Young Poet’s Conscience That Awakened 4·3

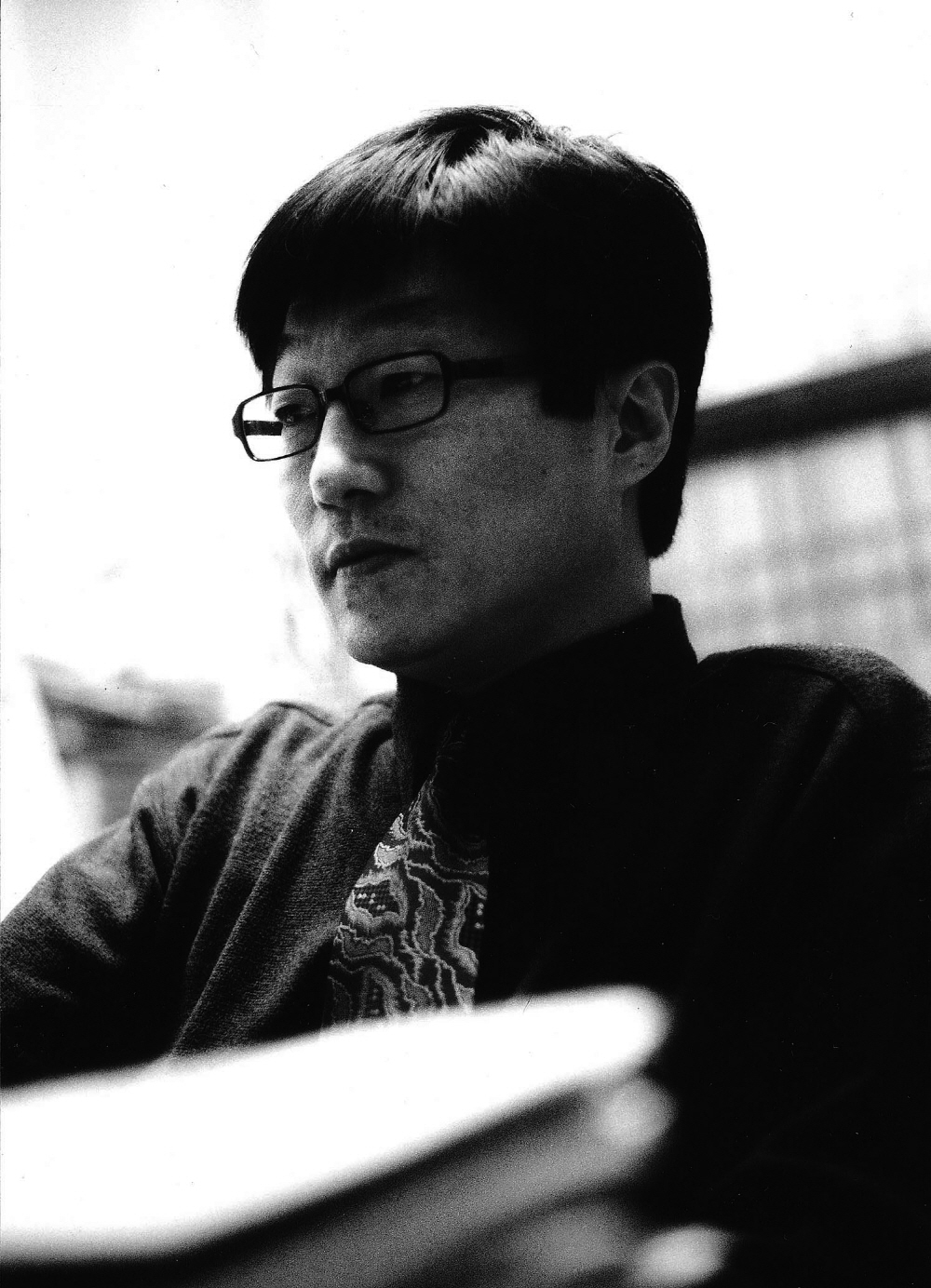

Jeju 4·3 has long been a taboo subject even though it was an incident of huge magnitude wherein 10% of Jeju residents lost their lives. When the Rhee Syngman regime collapsed due to the April 19 Revolution in 1960, the first movement to reveal the truth of Jeju 4·3 began. With the May 16 coup taking place the following year, those that led the movement were punished. In 1978, Hyun Ki-young published the novel “Sun-i Samch’on”, breaking the forced silence that had lasted for 18 years after the April 19 Revolution. But the novelist was taken and tortured by military intelligence, and the book was eventually banned from sale. Subsequently, none of Jeju residents openly spoke of Jeju 4·3. Lee San-ha’s long epic, ‘Mount Halla,’ released in 1987, was not only the first violation of the taboo nine years after the publishing of “Sun-i Samch’on,” but also the first cry that helped establish Jeju 4·3 as part of the nation’s history of resistance, and of the unification movement, going beyond the recognition of the event as a historical ordeal. I met and had an interview with Lee San-ha, the poet who was imprisoned for authoring the poem.

Interviewed and Arranged by Kim Jong-min, member of the Central Jeju 4·3 Committee

Photographed by Kim Ga-min, professional photographer

[Kim Jong-min (left), member of the Central Jeju 4·3 Committee, interviews Poet Lee San-ha.]

Lee San-ha

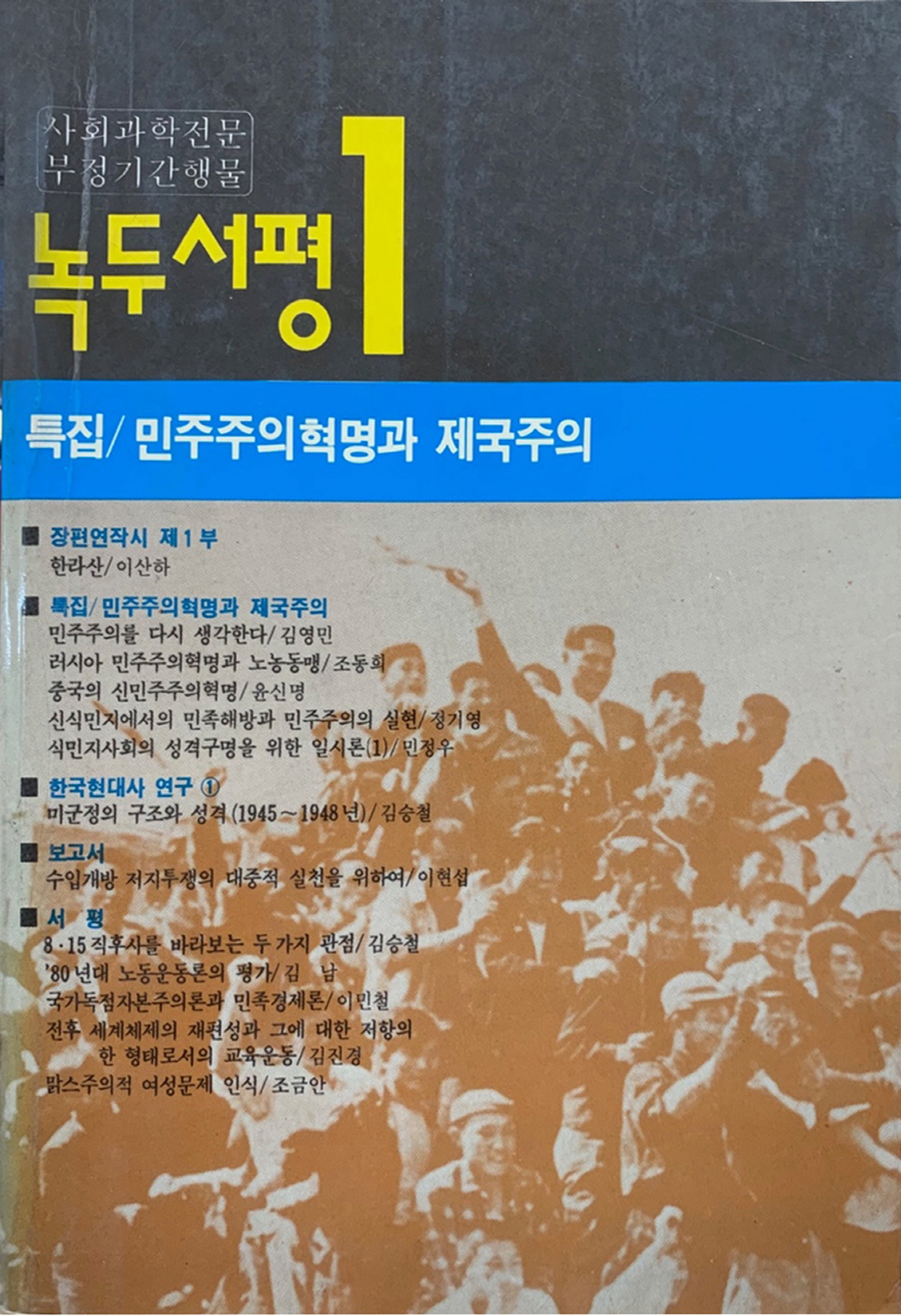

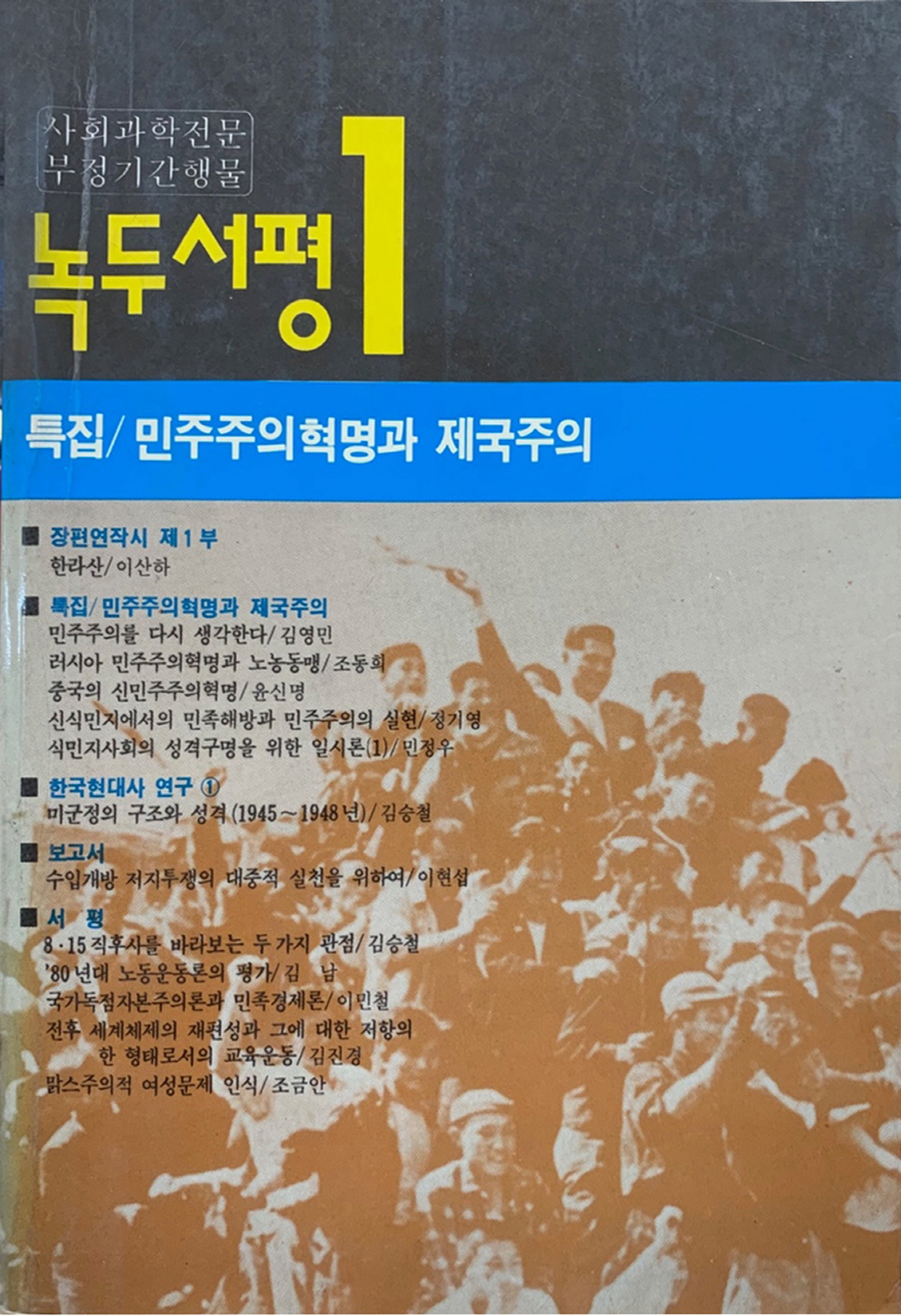

Lee San-ha is a South Korean poet whose real name is Lee Sang-baek. Lee was born in 1960 in Yeongil, Gyeongsangbukdo Province, and graduated from Hyegwang High School in Busan and the Department of Korean Language and Literature at Kyunghee University. In 1982, he made his debut as a poet by releasing the serial poem titled ‘The Play of Existence’ under the pen name of Yi Liung in “Poetry Movement”. Starting from 1986 when fleeing due to his involvement in the student movement, he published the People’s Daily and the Road to Democratization, writing a variety of propaganda as a member of the Propaganda Bureau of the People’s Youth League. In 1987, the activist caused great shock by releasing the epic poem ‘Mount Halla’ in “Mung Bean Review”, disclosing the massacre and truth of Jeju 4·3. The case that followed is called the most significant indictment of a literary work since ‘Five Traitors’ by another poet, Kim Ji-ha. Lee had been wanted for his involvement in the student movement for four years until he was arrested and imprisoned under the National Security Act. After being tortured and serving a jail term of a year and a half, he gave up writing for the following 10 years. After being released from prison, he later served as an editor for the Korea National Democratic Movement Federation, a steering committee member of the International Human Rights Center at the People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy, and the inaugural editor-in-chief of the “From People to People”, a magazine for human rights published by the Korean House for International Solidarity.

His books include the collections of his poems, titled “The Banality of Evil”, “Mount Halla”, and “With Thunderous Longing”; the coming-of-age novel “The Tin Iron Drum”; the collections of essays on his travel to a mountain temple, “As It Bloomed, It Falls” and “A Path to Jeongmyeolbogung Hall”; the collections of translated poems “The Pain of the Survivor” (poems authored by Primi Levi) and “The Collection of Poems by Che Guevara” (poems authored by Che Guevara).

Lee won the 32nd Kim Dal-jin Literature Award and the 18th Lee Yuk-sa Poetry Literature Award in recognition of his poetic expression from a critical perspective without avoiding the history and the reality of the times.

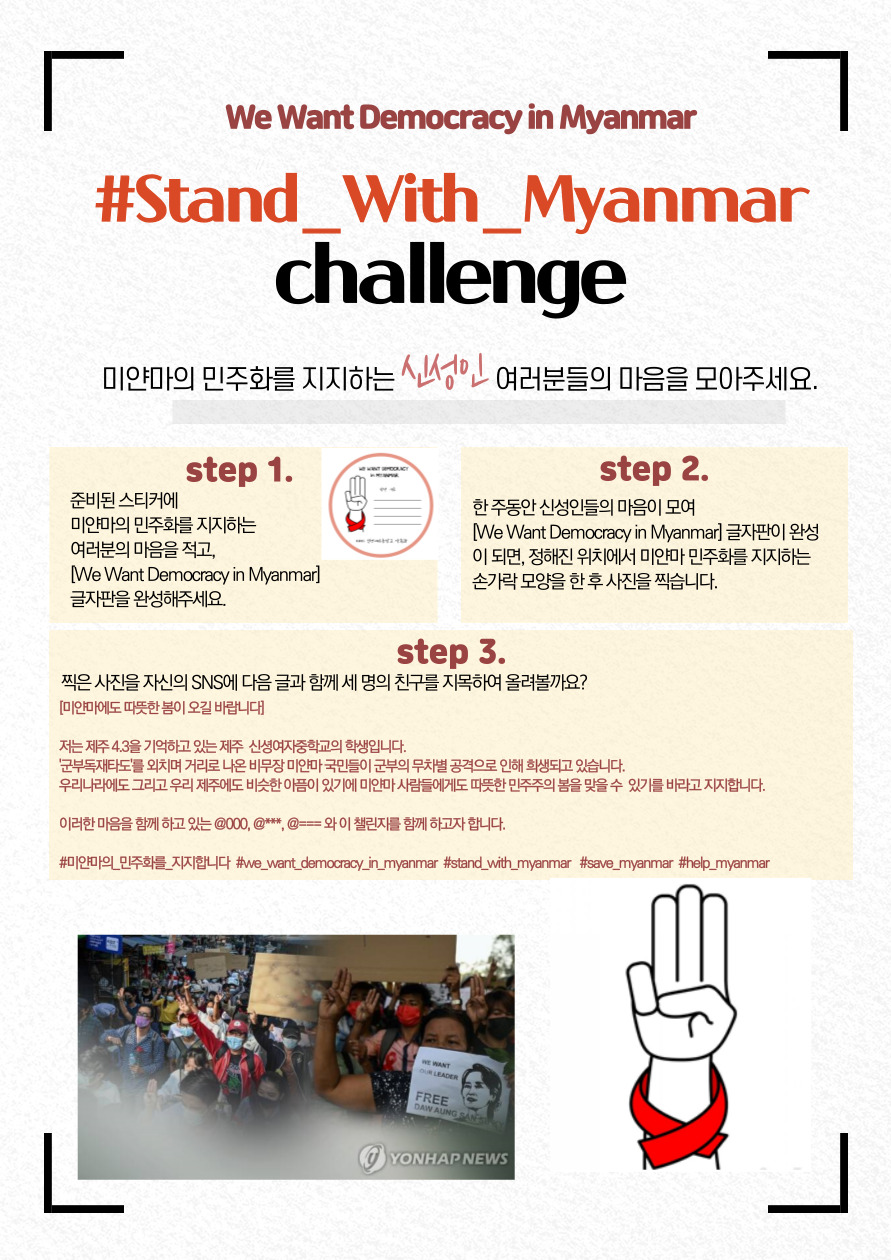

‘Mount Halla’, the epic poem he wrote on the theme of Jeju 4·3 and released in the magazine “Mung Bean Review” (March 1987) 35 years ago, begins as follows:

A land that can’t be reached without a tongue-biting wail

That can’t be climbed without toe-cutting anger

On Jeju Island

On Mount Jiri

And in every corner of the Korean Peninsula

Revolutionary warriors were furiously oxidized

Those who were for the liberation of the nation and the unification of the motherland

To all of them I dedicate this poem.

From the moment any literary piece appears in the world, it is the readers’ part to understand and feel the work. Could you introduce your poem ‘Mount Halla’ from the author’s perspective?

“In general, there are two main ways to deal with any major historical event or massacre. The first is to describe the event as a victim-centered tragedy and the other is to view the event as a protest. And ‘Mount Halla’ is a poem that focuses on the protest side. But now that I think about it, it is most regretful that I ended it with only Part 1. I wish I would have spent two more months to complete a second part.”

What message would you try to convey in Part 2 of ‘Mount Halla’?

“Recently, I wrote a poem titled ‘All of This Is Because’. So, why did the young men and women keep climbing Mt. Halla? I think that is the most important part. It was obvious that they would lose, but they continued to climb the mountain. That part seems to be the most important.” ‘All of This Is Because’, in Lee San-ha’s collection of poems, “The Banality of Evil” (Changbi, 2021), can be roughly translated as follows:

Although knowing they’re going to fall like autumn leaves and

Knowing they’ll burst as bubbles,

Waves soar and scream as they crest because…

Break their backs in one falling crash because…

The camellia flowers’ blood slowly runs down the side of the knife

Forming as tear drops on the point of the blade because…

On Mount Halla, which emanates a mood of loss

The young keep going up because…

And all of this is because……

I wonder how the poem ‘Mount Halla’ was born.

“I was told that a publisher wanted to release a translation of ‘The History of Blood’ (《濟州島 血の歷史-4·3武裝鬪爭の記錄》), written about Jeju 4·3 by a Korean named Kim Bong-hyun living in Japan, but was hesitating because he was scared. The first time I learned about Jeju 4·3 was when I read ‘Sun-i Samch’on’ released in “Creation and Criticism” in my third year of high school. The novel told the story of hundreds of people slaughtered in a small town, and it was so unthinkable that I thought, ‘Did this really happen?’ I couldn’t really feel it in my bones. I read a lot of social science books in high school and many other books after I joined an underground circle in college. But there was no mention of Jeju 4·3 anywhere. So, I trembled all night when I came to the translation of ‘The History of Blood’. And I thought to myself, ‘Oh! There was such a historic revolution in Korea’s modern history, and I didn’t know that and only studied the revolutions of other countries!’ So, I thought I’d publish this first. But even Georeum, the most progressive publisher at the time, hesitated to publish it. At that time, I was wanted by the police but was responsible for the planning division at the Mung Bean publishing company. So, I went to the company with the manuscript and persuaded them. But one day, the CEO suddenly suggested, ‘Why don’t you write the content of the book in a poem?’ The proposal itself shocked me. I said, ‘Why are you telling me to write it!?’ I thought it was like a bomb. I was a bomb carrier at first, but if I accepted his suggestion, I would become a bomb maker.”

Translating literature will make you a ‘bomb-carrier’, but writing a poem will make you a ‘bomb-maker’?

“Yes, that’s a whole different matter. So, I thought about what to do all night long. Should I accept this bomb or not? But then I felt insulted by myself. What would happen to me if I accepted this bomb? If I wrote this and if the bomb exploded, I might end up dying. And if I survived, I might live in a cell for decades and be released with silver hair. I thought of my parents and all sorts of other things, eventually becoming very timid. It felt like there were so many other ‘my selves’ inside me. That is, there was me that had been expressed, but there were so many other inside me that had not been revealed.”

Despite that much consideration, what made you decide to write a poem?

“I thought I wouldn’t be able to write for the rest of my life if I didn’t write it. At that time, there were two motivations. Reading Kim Ji-ha’s poem ‘Five Traitors’ made me swear. Like, ‘Holy xxx, this is the real thing, a real poem. Someday I’m going to write a poem like this,’ I thought to myself. I think things turned out as I had said. And another reason is because of what I went through at the temple. My maternal grandmother was a Buddhist nun with a husband. I used to visit her temple every vacation during my high school years to write poems and read books. One day, a young monk came and practiced meditation facing the wall all throughout the day. It was hot in the middle of summer, and he took off his upper garment and looked at the wall. Looking in from outside, I saw so many dark mosquitos covering his whole back. But the monk didn’t want to use mosquito nets, and even refused to burn mosquito repellent, saying that it is also a chemical killing.”

[Lee San-ha at the time the epic poem ‘Mount Halla’ was released in “Mung Bean Review” (1987)]

Did the meeting with the Buddhist monk lead you to write ‘Mount Halla’?

“It was vacation, so I traveled all over the country with the monk. The first place I visited was Unmunsa, a temple for female Buddhist monks in Cheongdo, Gyeongsangbukdo Province. One day when I entered the Buddhist sanctuary at dawn, hundreds of Buddhist monks of the same age as me, a high school student, sat reading Buddhist scriptures, and the scene was so majestic. I wondered what they were concentrating on or what point they were trying to reach. They belonged to a completely different level of the world from mine. Until then, I didn’t have any level that I sought to reach in terms of poetry. I was only interested in some poetic techniques or messages, without thinking about what the ultimate attainment of being a human was. Then, I was shocked and even cried when hearing the young female monks reciting manuscripts. As the vacation ended, I parted with the young monk I had traveled with after taking our last trip to Jeongmyeolbogung in Sangwonsa, a temple in Odaesan Mountain. But another monk who gave us a ride said, ‘That monk is very dangerous. I’m worried that you’ll get seriously injured.’ What he meant was that one of the most dangerous practices of monks is the practice of copying manuscripts with their own blood. So, I encountered ‘Five Traitors’ when I was most sensitive in high school, and I met a Buddhist monk who used his own blood to copy manuscripts, and also young female Buddhist monks of my age. I was shocked by the way they were so immersed in trying to achieve a certain level, and those images came to my mind when I hesitated to write the poem ‘Mount Halla’. I could refuse to write it and let others do it, but then what would become of me? If that was my destiny at the time, I wished I didn’t have that destiny at all.”

It means that your high school experience influenced your perspective of values and your spiritual world. So, what would it be like if you wrote Part 2?

“It would feature a further development of the situation (after the execution of Moon Sang-gil, who assassinated Park Jin-kyung). But it is my guess that after the Battle of Uigwi-ri or after June 1949 when Lee Deok-gu (Chief Commander of the armed resistance forces) died, it would have been difficult to fight a true battle. A battle can take place only when the power on both sides is equal. Instead, it seemed like the forces actually entered the state of a mental battle. On May 26, 1980, there were 500 people left in the Jeollanamdo provincial government building in Gwangju. Yoon Sang-won, a spokesman for the 500 civilian resistance soldiers, told foreign reporters, ‘Today we will lose. You wonder why we don’t leave this place when it’s obvious that we’re going to lose? We can’t greet the airborne troops with a white flag, can we? Tonight we will be defeated, but history will record us as winners.’ I see the basis of that spirit was the spirit of Jeju 4·3. So, I asked why they kept going up the mountain, knowing that they were going to lose and eventually die? I ask why the civilian resistance forces refused to leave the provincial government building even though they knew they were going to die.”

You were wanted by the police because of authoring ‘Mount Halla’. How did you get arrested?

“While I was wanted, Roh Tae-woo, the presidential candidate of the Democratic Justice Party, made the so-called June 29 Declaration to accept the direct presidential election system. So, the government had to hold a presidential election at the end of the year. The Ministry of National Security set up two plans to create a mood focusing on public security in case of candidate unification between YS (Kim Young-sam) and DJ (Kim Dae-jung). One was to make the most of the bombing of a Korean Air plane, and the other was to define a labor movement team in Incheon, which I was involved in, as an anti-state organization and use me as a victim. Anyway, the police tortured a worker from the labor movement team in Incheon to contact me and arrest me. The worker couldn’t resist the torture and had no choice but to follow the police operation. But when I was in prison, he killed himself out of guilt.”

What happened after you were arrested?

“The police interrogated me with torture by water, so that they could use my case for the presidential election, which was just around the corner (December 1987). To manipulate a larger-scale case, they kept asking who the mastermind was, saying that a 28-year-old young man alone couldn’t have written the poem. There was no one behind me, so how could I say who it was? It was also ridiculous to say, ‘Kim Bong Hyun ordered it.’ I hadn’t even met him. There were a few people that I had tried to protect even though I was being tortured with water and sleep deprivation. Because I didn’t inform on Yoo ○○, Han ○○, and Lee ○○ of the People’s Youth League Propaganda Bureau to the police at the time, I can still see them without feeling guilty. But as the presidential election was getting closer, the atmosphere changed little by little. The police were worried that it would cause trouble if their abusive handling of a poet would lead to the agreement of a single candidate in the progressive circles and the change of the regime. However, even lawyers who were famed for being at the forefront of the nation’s democratization refused to defend me. And literary figures such as Ko ○, Baek ○○, and Shin ○○ didn’t want to testify for me. I wanted them to speak out for freedom of literary expression because ‘Mount Halla’ is a literary work and not something that benefits the enemy. But no one came forward. At that time, they didn’t know who I was, so maybe they suspected that I was a real commie or had a resident espionage agent behind me.”

Probably, they thought it was a matter of a different level to defend someone who might be a real spy, not advocating for someone involved in the democratization movement.

“That’s right. In society at the time, being involved in espionage cases came at a harsh price, unlike being involved in the democratization movement. Then, lawyer Hong Seong-woo, who had initially refused to defend me, changed his mind and became my lawyer. After hearing about it, he might have thought that if he didn’t take the case, he would stain his reputation as an advocate for democratization.”

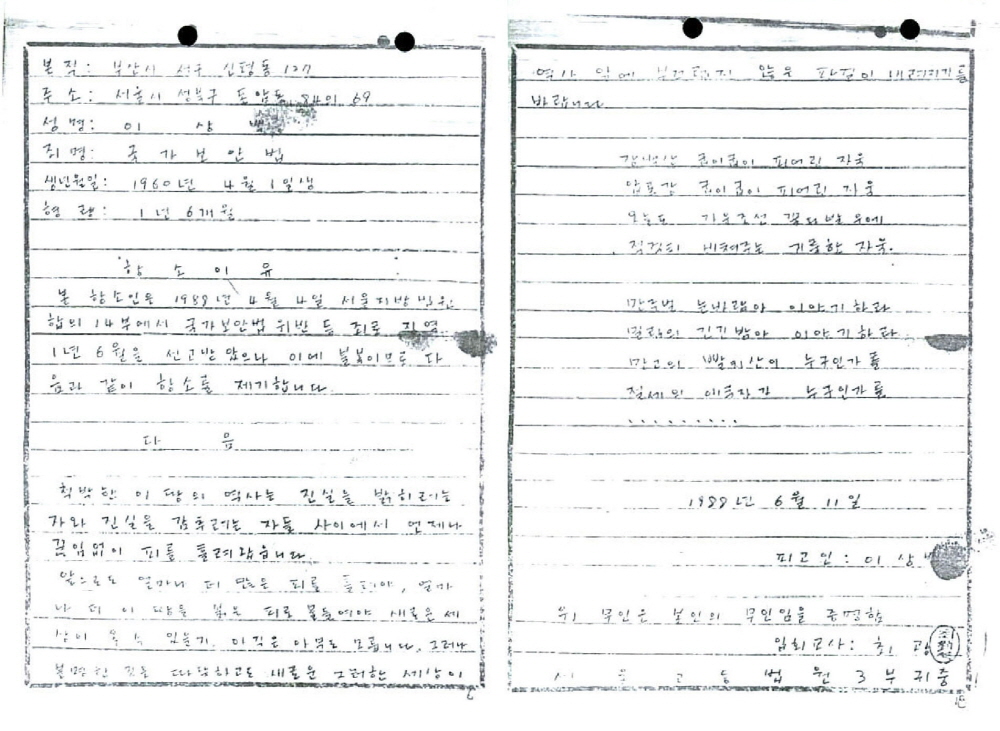

Looking at the court ruling, the first trial judge was Park Young-mu. The judge eventually accepted the prosecution’s indictment as it was and sentenced you to imprisonment. What was the key argument of the prosecution then?

“At first, they tried to indict me under the false charge of ‘forming an anti-state organization’ under the National Security Act. When it seemed impossible, the case was made that I ‘inspired others to praise’ Kim. Prosecutor Hwang Kyo-ahn said to me, ‘I will make you eat rice with beans forever,’ and he was especially excited to see my ‘Reason for Appeal’. I wrote ‘General Kim Il-sung’s Song’ in it. My defense counsel responded, ‘Are you out of your mind and want to get yourself killed?’”

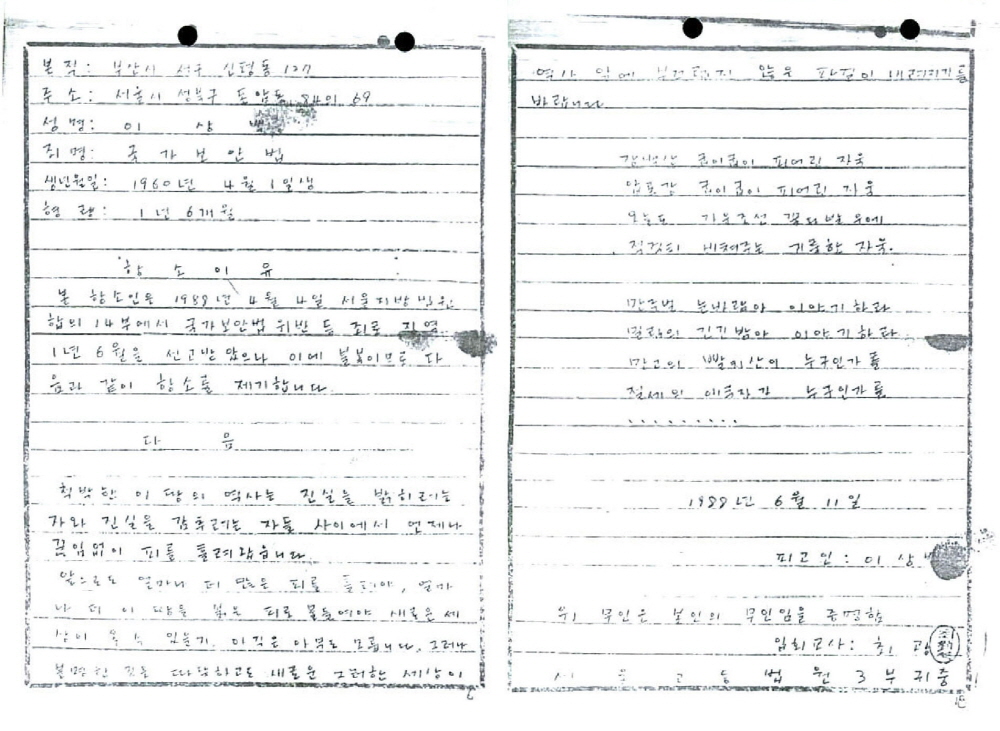

[Lee Sang-ha’s “Reason for Appeal” contained General Kim Il-sung’s Song, throwing the prosecution and the court into utter chaos.]

Why did you write General Kim Il-sung’s song on the Reason for Appeal?

“It’s for freedom of expression and freedom of speech. The way I see it, it would be the ultimate freedom of expression and speech to be able to say, ‘Long Live Kim Il-sung’ or ‘General Kim Il-sung’s Song’. Anyway, not only the prosecution but also the court turned upside down because of my Reason for Appeal. So, Hwang Kyo-ahn investigated my case again to punish me more strongly. It was the American writer Susan Sontag who saved me at that time.”

Before and after the appellate court ruling, there were two big events in Korea. One was the 1988 Olympics and the other was the annual PEN Congress. Susan Sontag, the then president of PEN America, used the PEN Congress to pressure the Korean government.

“Yes. A committee to save my life was organized in the United States, and then in Europe and Japan. Susan Sontag filed a petition with Cheongwadae, but the response was not good. So, she appointed me as an honorary member of PEN America, where she was the chairman. Then she visited Seoul and said she would cancel the PEN Congress scheduled to be held in Seoul if the government refused to release me. She put more pressure on the government, saying that the 1988 Olympics would also face difficulties. At that time, she was named as the world’s most influential person by the Times. So, even conservative writers who wanted to host the international event came forward and urged them to release me. And Hwang Kyo-ahn couldn’t do any more harm to me.

At the end of last year, you filed for a retrial against the indictment for writing ‘Mount Halla’. Those who request a retrial usually claim that they only made a false confession because of torture and did not commit a crime, or that they were unfairly convicted because of poor investigation or manipulated evidence. For what purpose did you file a retrial?

“The espionage case is where evidence is manipulated when there is none. My case had something to be used as evidence; that is, ‘Mount Halla’. It’s just that the interpretation of the evidence was different. And now I am trying to correct that interpretation. What I argued through the poem was that Jeju 4·3 rejected the election, opposing the formation of the South Korean government alone in favor of creating a unified government. So, I thought that leaving me guilty would violate the purity of values reflected in Jeju 4·3.”

Then, I’d like to talk about what you have just mentioned. In the past, the military regime defined Jeju 4·3 as a riot or a communist riot, and those who said or wrote the opposite were punished or suppressed just as you experienced. In 2008 and 2018, which marked the 60th and the 70th anniversaries of Jeju 4·3, respectively, many people raised their voices over the proper naming of Jeju 4·3, claiming that we should now call it “Jeju 4·3 Resistance”. What are your opinions on the proper naming of Jeju 4·3?

“The so-called Gwangju 5·18 is referred to as the Gwangju Resistance, officially the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement. I would like to call 4·3 the April 3 Unification Movement or the April 3 Resistance for Unification.

What would you like to write about in the future?

“I’m planning to write about the Inhyeokdang incident. I chose the title ‘Camellia Flowers’.”

Let’s go eat beef together for dinner. I heard that you had colon cancer surgery last year. Will it be okay for a colon cancer patient to eat beef?

“I got much better now, so it is okay.”