Unveiling the Silenced Lives of Jeju 4·3 Women through Film

Written by Kim Hyeong-hoon, Editorial Committee Member

Written by Kim Hyeong-hoon, Editorial Committee Member

The history we know is merely a fragmented “piece.” Even when we piece together these fragments, it’s impossible to create a complete historical picture. This is why historians delve into the hidden sides of fragmented puzzles. Yet, the results are often incomplete, and there’s a reason: they only focus on “half” the picture. That “half” has always been history viewed from a male-centered perspective. Isn’t this evident even in world-changing events? The central figures in short historical “pieces” that depict the leaders of wars, the emergence of new religions, and the invention of technologies are almost always men. Where have all the women gone?

Jeju 4·3 is no different. Women’s stories rarely come to light. While it’s true that many of the victims were men from Jeju, the hidden stories of the women in the background are often left unknown. Perhaps it’s our inherent tendency to avoid discussing or seeking out the stories we try to hide, the ones we choose not to speak of or seek out. Fortunately, some films have emerged to shed light on the hidden stories of women in Jeju 4·3.

# 《The Daughters of That Day》 ― Different Lands, Shared Pain?

Smoothly carved black stones form tombstones. The neatly arranged stones symbolize death, and the engraved three-character names tell another painful story of Jeju 4·3. What lies hidden behind the countless deaths marked by these stones? 《The Daughters of That Day》 begins its narrative by panning over the rows of black tombstones at the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park.

Jeju became a blood-soaked massacre site following the uprising on April 3 in 1948. Stigmatized as “communists,” the people of Jeju faced scorched-earth operations designed to kill them. For decades, the unjust deaths were silenced by the admonition to “keep it to yourself.” Decades of untold stories followed.

In Rwanda, the death of President Juvénal Habyarimana in April 1994 triggered the Hutu extremists to massacre the Tutsi and moderate Hutus. Within just 100 days, one million lives—10% of Rwanda’s population—were lost.

Oral historian Yang Kyeong-in meets with Jeju 4·3 victims, documenting their stories. Along the way, she encounters Pacis, a young woman from Rwanda. Though they lived in different times, they share a commonality: they are daughters of women who survived genocide.

After graduating from college, Yang worked as a government employee before becoming deeply involved in Jeju 4·3. Her growing engagement with Jeju 4·3 caused friction with her mother, who had barely survived the tragic period herself. To her mother, it must have seemed reckless for her daughter to confront Jeju 4·3 head-on.

History is widely recognized as being male-centered and written by the victors, and Jeju 4·3 is no exception. For decades, the victims were forced to remain hidden, making the perpetrators the victors.

Yang states, “If you win, you become the victor and the ‘good’ side, and if you lose, you’re branded a traitor. Jeju 4·3 was no exception.”

Jeju 4·3 was a conflict that led to death. Thankfully, the Jeju 4·3 Special Act was enacted, creating opportunities for reconciliation. Some began to seek healing through this process. Yang, who had countless arguments with her mother, eventually reconciled with her because of April 3—ironically, through her work related to the tragedy. Jeju 4·3 both posed a problem and provided the solution.

What about Rwanda? Unlike Jeju, Rwanda lost a population dozens of times greater in a short period. Strangely, despite the higher death toll, reconciliation occurred more swiftly than in Jeju. From the victims’ perspective, this is hard to comprehend. Yang travels to Rwanda with Pacis to seek answers.

Genocide is nearly impossible to explain in words. It is painful for those who recount it and equally for those who listen. Pacis, who had been translating the oral accounts of Rwandans, finds herself unable to speak anymore. Listening to such vivid accounts of recent deaths is already difficult—how could she retell those stories?

Two individuals from the massacre 30 years ago appear in the same frame: Franco, a perpetrator, and Maria, a victim. Even in a documentary, could such an encounter be possible? The answer lay in their reconciliation. Maria, the victim, makes a weighty statement. It echoes the sentiments of Jeju mothers who endured the pain of Jeju 4·3.

“I came to understand that without forgiveness, I couldn’t raise the children who remained. Holding onto resentment, anger, and pain makes it impossible to do anything.”

Once forgiveness was granted, everything around her changed. When it came time to plant beans, Maria found the field already cultivated. The person who secretly helped? Perpetrator Franco.

# 《Voices》 ― A Deeper Look at the Pain of Jeju Women

It is utterly dark. A light shines on a house. A family carries out munjeonje (a ritual of placing a meal at the doorstep to honor spirits or appease deities), followed by jesa (A traditional ritual to honor ancestors on the anniversary of their death). It’s a familiar scene of jesa in Jeju. But who is the subject of the ritual ceremony? It seems there isn’t even a single photo to remember them by. A memorial plaque replaces the portrait, inscribed with the words, ‘The place where Grandma and Grandpa return.’ That says it all.

Dec. 16, 1948. A bright full moon lit up the night, as the residents of Tosan Village were summoned at midnight. It is unclear who first said it, but the claim was made that “everyone in Tosan Village aged 18 to 40 joined the South Korean Workers’ Party,” prompting the police to round up the residents. All men in that age group were separated, and some women were included in their group, too. Someone who remembers the event recounts it as follows:

“The unmarried women were told to look at the moon. Since there was no electricity back then, they used the moonlight to pick out the prettiest ones and took them away. The police called out to the women, saying, ‘You, come forward; you, come forward.’ There must have been about 20 of them.”

“The women were taken to Pyoseon Village along with the men. Over two days, on the 18th and 19th, the men were massacred. The women were killed shortly afterward, about a week later, when the military unit moved to another location. They probably massacred the women to prevent their secrets from being exposed if they were left alive.”

That secret was that the women had been used as sexual playthings by the Northwest Youth League and the police. This didn’t only happen in Tosan Village. Young women massacred at Seoubong Peak in Hamdeok Village had faced the same fate. Among the 15,000 victims of Jeju 4·3, there isn’t a single official record stating that any were killed because they were women. There are multiple reports of young women dying at the same locations. Tracing these reports reveals clues, which 《Voices》 explores and presents. There is a scene where someone talks about his older sister’s death.

“My eldest sister’s name was Lee Hyeon-hwan. On Dec. 26, 1948, she was executed at Monjugial, a coastal cliff north of Seoubong Peak in Bukchon Village. She was about 21 years old. She had committed no crime, except the crime of being beautiful. Her only crimes were being young and beautiful.”

Yang Yoon-sik, another family member of a Seoubong victim, recalls the lamentations his mother used to share. In those stories, there were young women. The young women were taken to detention centers for no other reason that they were young. They hadn’t committed any crimes, nor did they have any reason to. Like the faces of the women illuminated by the bright moonlight in Tosan Village, their youth alone was the reason. The real reason for their deaths was the authorities’ desire to bury their secrets.

Why have we been unaware of this history until now? Silence exists here. Could it be that Jeju women chose silence as another way to live their lives? For those who had endured the bloody horrors triggered by countless ‘revelations,’ silence might have been Jeju women’s unique way of protecting themselves from the new horrors that speaking out might bring. The documentary 《Voices》 skillfully reveals the stories of Jeju women who had no choice but to remain silent. The documentary can be summarized through the narration of Cho Jung-hee, Jeju 4·3 researcher who has spent 20 years collecting oral histories. Everything is encapsulated in her words.

Why have we been unaware of this history until now? Silence exists here. Could it be that Jeju women chose silence as another way to live their lives? For those who had endured the bloody horrors triggered by countless ‘revelations,’ silence might have been Jeju women’s unique way of protecting themselves from the new horrors that speaking out might bring. The documentary 《Voices》 skillfully reveals the stories of Jeju women who had no choice but to remain silent. The documentary can be summarized through the narration of Cho Jung-hee, Jeju 4·3 researcher who has spent 20 years collecting oral histories. Everything is encapsulated in her words.

“Whether they were sexually harassed, assaulted, or forced into unwanted marriages and suffered lifelong trauma, women are not included in the category of Jeju 4·3 victims. They couldn’t even leave their names on memorial monuments. What isn’t recorded in official history will disappear with time. That’s what scares me. At first, I thought we didn’t know because they didn’t tell us. But the elderly ladies spoke of their wounds through silence, tears, and sighs. We just didn’t try to understand. Although history doesn’t record it, I believe their voices still live on in Jeju’s waves, stones, and winds.”

Come to think of it, there are forgotten women in my own family history too—the wives of my eldest and third uncles. Where might they be resting after withering away in the prime of their lives? No one ever looked after them. I feel deeply sorry.

Photographer Kang Jeong-hyo

Photographer Kang Jeong-hyo Documenting Jeju 4·3 requires deep affection and persistence. Photography, in particular, demands presence at the scene. Photographer Kang Jeong-hyo has long captured the shadows and lights of Jeju 4·3 through the expressions of bereaved families. His camera has consistently been present at sites of excavation of victims’ remains and investigation into the truth of Jeju 4·3. Additionally, Kang has raised awareness of Jeju 4·3 through the publication of photo books and exhibitions. He also co-chaired the Memorial Project Committee for the 70th Anniversary of Jeju 4·3. Here, we delve into his journey.

Documenting Jeju 4·3 requires deep affection and persistence. Photography, in particular, demands presence at the scene. Photographer Kang Jeong-hyo has long captured the shadows and lights of Jeju 4·3 through the expressions of bereaved families. His camera has consistently been present at sites of excavation of victims’ remains and investigation into the truth of Jeju 4·3. Additionally, Kang has raised awareness of Jeju 4·3 through the publication of photo books and exhibitions. He also co-chaired the Memorial Project Committee for the 70th Anniversary of Jeju 4·3. Here, we delve into his journey.

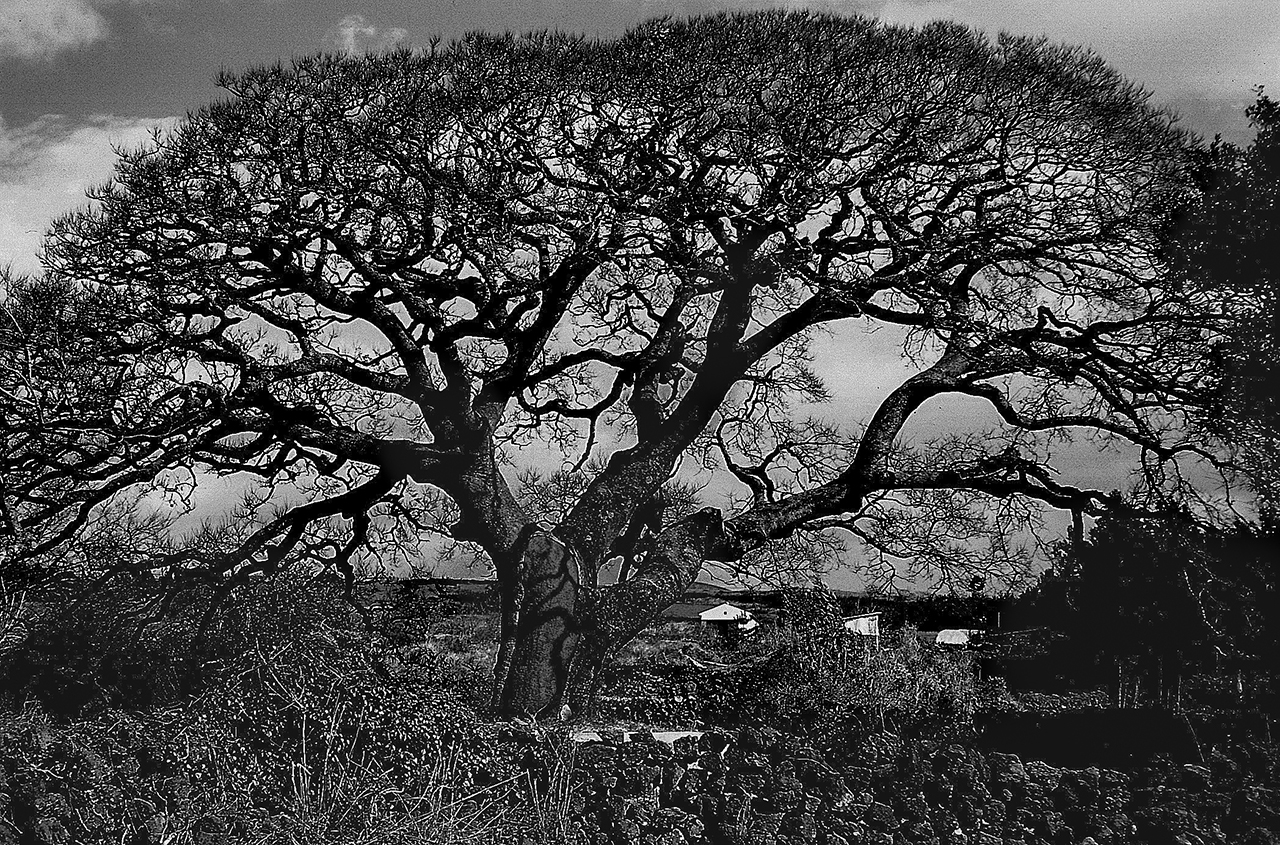

Pongnang at destroyed neighborhood Sambatguseok in Donggwang Village (ⒸKang Jeong-hyo)

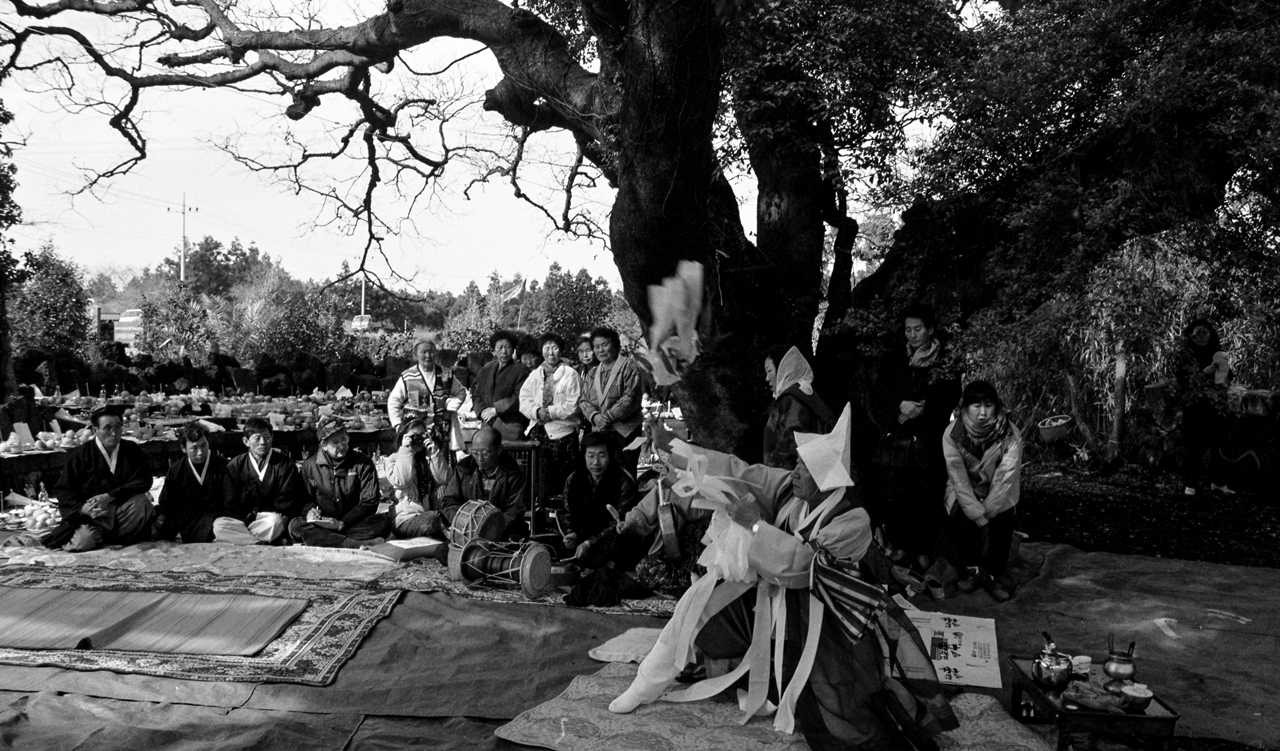

Pongnang at destroyed neighborhood Sambatguseok in Donggwang Village (ⒸKang Jeong-hyo) Bonhyang Shrine for the guardian sprit of Waheul Village (ⒸKang Jeong-hyo)

Bonhyang Shrine for the guardian sprit of Waheul Village (ⒸKang Jeong-hyo) Written by the Editorial Office

Written by the Editorial Office A joint performance by the Jeju Provincial Art Troupe and the Jeju City Choir takes place as a pre-ceremony event.

A joint performance by the Jeju Provincial Art Troupe and the Jeju City Choir takes place as a pre-ceremony event. Approximately 10,000 people, including survivors and bereaved families of Jeju 4·3, Jeju residents, and representatives from the government and political parties, fill the venue.

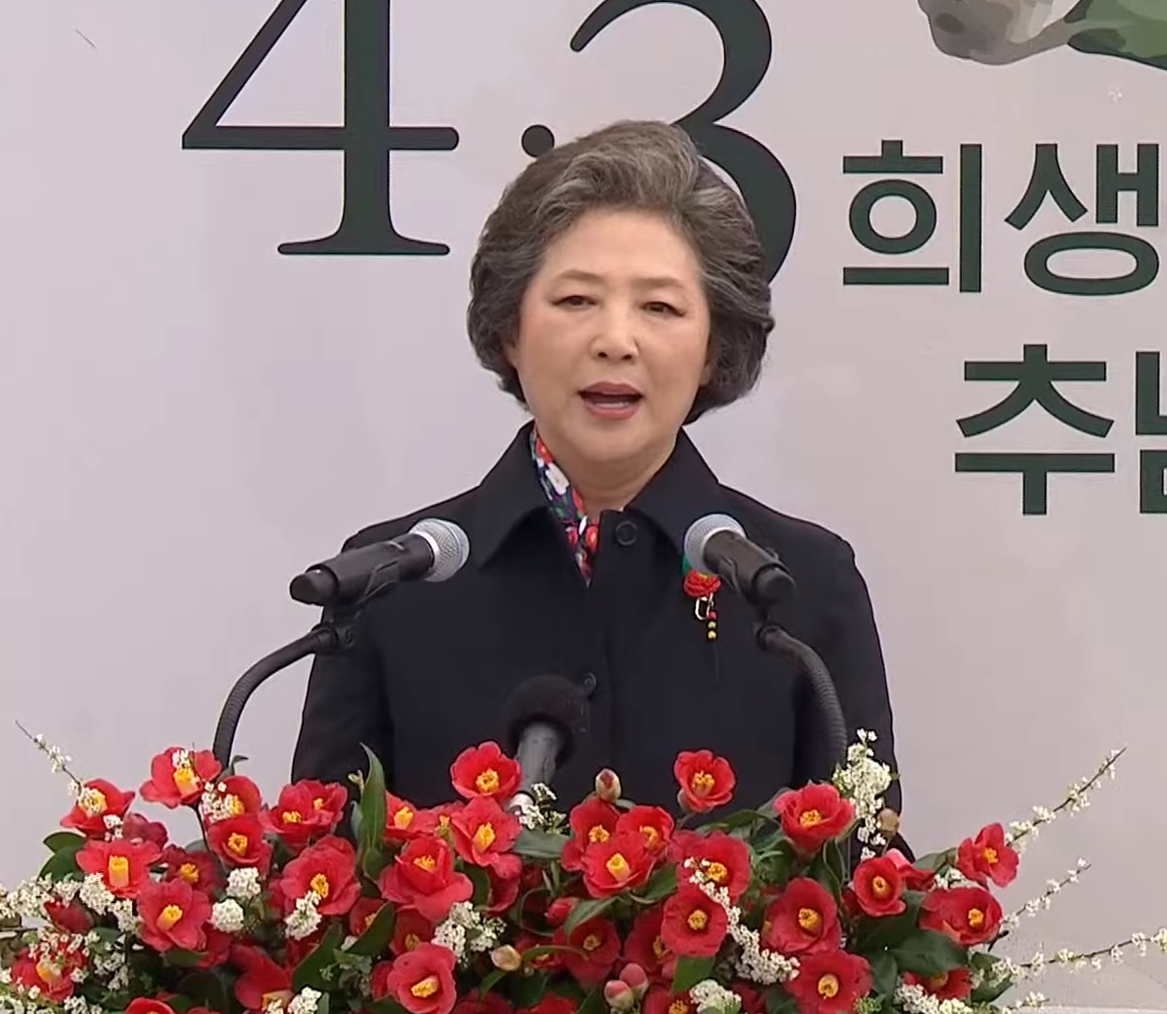

Approximately 10,000 people, including survivors and bereaved families of Jeju 4·3, Jeju residents, and representatives from the government and political parties, fill the venue. 01: Actress Go Doo-shim introduces the story of Kim Ok-ja, who lost her father at the age of five during Jeju 4·3.

01: Actress Go Doo-shim introduces the story of Kim Ok-ja, who lost her father at the age of five during Jeju 4·3. 02: Kim Ok-ja sheds tears as she meets her father, whose face is reconstructed using artificial intelligence, for the first time in 76 years, while her granddaughter Han Eun-bin embraces her.

02: Kim Ok-ja sheds tears as she meets her father, whose face is reconstructed using artificial intelligence, for the first time in 76 years, while her granddaughter Han Eun-bin embraces her. 03: Singer Insooni’s song “Father” brings tears to many.

03: Singer Insooni’s song “Father” brings tears to many.

Along with the letter reading, the restored image of Kim Ok-ja’s father, recreated using AI, appears on the large screen at the memorial site.

Along with the letter reading, the restored image of Kim Ok-ja’s father, recreated using AI, appears on the large screen at the memorial site.

01: At 10 a.m., sirens sound across Jeju Island for a minute of silence to honor the spirits of the Jeju 4·3 victims.

01: At 10 a.m., sirens sound across Jeju Island for a minute of silence to honor the spirits of the Jeju 4·3 victims. 02: The Jeju 4·3 Camellia Supporters, the official university student supporters of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, are offering flowers and incense.

02: The Jeju 4·3 Camellia Supporters, the official university student supporters of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, are offering flowers and incense. 03: Despite the inclement weather, the survivors and the bereaved families of Jeju 4·3 gather at the memorial site.

03: Despite the inclement weather, the survivors and the bereaved families of Jeju 4·3 gather at the memorial site.