Special Report: The 1st Jeju 4·3 Journalism Awards Ceremony

The 1st Jeju 4·3 Journalism Awards Ceremony

Co-hosted by the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, Journalists Association of Korea, and Journalists Association of Jeju

– Winners selected in gratitude for helping set Jeju 4·3 history right

– Reports of high standards recognized befitting the dignity of the awards

Editing Office

“History is an unending dialogue between the present and the past.” Not even approaching the spirit of the well-known quote, the history of Jeju 4·3 remained interrupted for a long period of time. During that time, which spanned from the killing of some 30,000 people by state violence through the tyrant military regimes established in Korea, Jeju 4·3 was considered taboo and the families of the victims were forced to live a silenced life. Meanwhile, there have been journalists who attempted to resume the long-halted dialogue of history, unearthing what had been buried from the eyes of the public. This gives great significance to the Jeju 4·3 Journalism Awards launched by the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation. The statutory foundation committed to the matters concerning Jeju 4·3 inaugurated the awards this year in recognition of efforts by journalists and media agencies and organizations. The winners were selected from the candidates that contributed to ▲ Revealing the truth of Jeju 4·3 and restoring honor to the victims; ▲ Inheriting and uplifting peace, human rights, democracy, and justice, which are the spirits valued throughout Jeju 4·3 and its successive movement; and ▲ Raising awareness of the historical event in Korea and in the world beyond. – Editor

The winners of the 1st Jeju 4·3 Journalism Awards were announced on Dec. 16, 2022, in the Grand Auditorium of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Memorial Hall. The award ceremony was co-hosted by the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation (President Koh Hee-bum), Journalists Association of Korea (President Kim Dong Hoon), and Journalists Association of Jeju (President Jwa Dong-cheol).

▲ The Grand Prize was given to KCTV Jeju for its report “Jeju 4·3 Special Report – Memories of the Land” (by Kim Yong-min, Kim Yong-won, and Moon Su-hee). ▲ The Excellence Award announced the winner in the categories of △ Newspaper/Publication: The Hankyoreh “Special Coverage: The 70th Anniversary of Jeju 4·3 – Asking Camellias” (by Huh Ho-joon) and △ Broadcasting/Film: KBS Jeju “Investigation K Trilogy: Jeju 4·3 and Fabricated Spy Cases – Memories That Fade” (by Kang Jae-yoon, Na Jong-hoon, Bu Su-hong, and Shin Ik-hwan). ▲ The Rookie Award was presented to Chung-Ang University Magazine “Chung-Ang Culture” for “Recalling Jeju 4·3 with the Revised Bill on the Jeju 4·3 Special Act” (by Kim Hyeon-kyeong). Award plaques were given to each winner, along with the prize money of △ 10 million won for the Grand Prize, △ 5 million won for each Excellence Award, and △ 3 million won for the Rookie Award.

Key politicians and scholars attended the award ceremony, including Kim Dong Hoon, president of the Journalists Association of Korea; Jwa Dong-cheol, president of the Journalists Association of Jeju; Kim Kwang-soo, Jeju Superintendent of Education; Han Kwon, chairperson of the Jeju Provincial Council’s Jeju 4·3 Special Committee; Cho Sang-beom, director of Jeju Provincial Special Self-Governing Administration Bureau; Yang Jo Hoon, member of the National Jeju 4·3 Committee; Lee Moon-gyo, former president of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation; Oh Im-jong, chairperson of the Association for Bereaved Families of 4·3 Victims; and Heo Young-sun, director of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute.

Koh Hee-bum, president of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, delivered an opening address to recognize and appreciate the strenuous efforts made by the winners of the 1st Jeju 4·3 Journalism Awards. The prominent journalist also said, “It is my anticipation that journalists will always stand with us to set the history of Jeju 4·3 right.”

** The winners and the organizers of the 1st Jeju 4·3 Journalism Awards take a commemorative photo after the award ceremony.

■ Grand Prize: “Jeju 4·3 Special Report – Memories of the Land”, KCTV Jeju

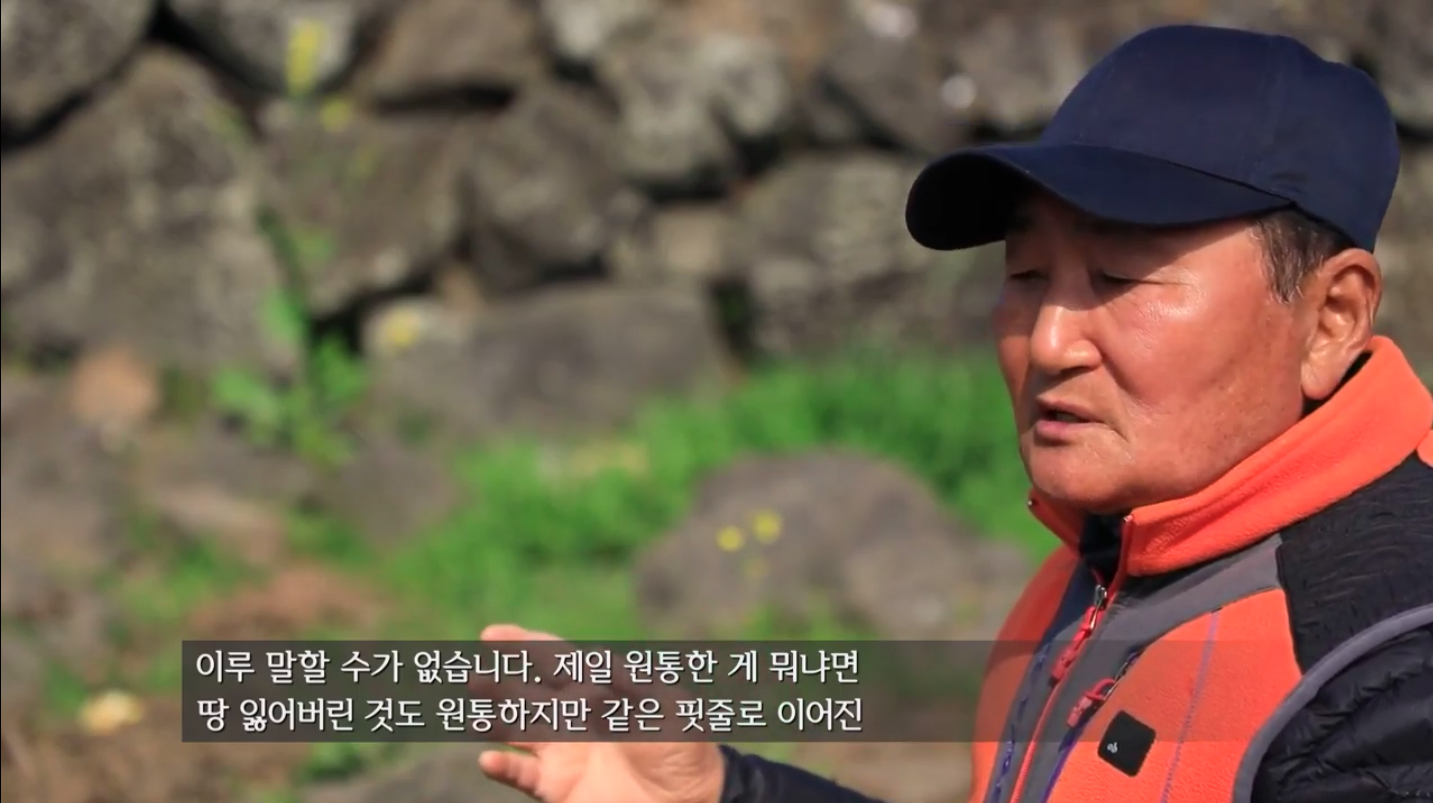

“Jeju 4·3 Special Report – Memories of the Land” covers the stories of those who not just lost their loved ones but were also deprived of the land where they had lived for generations, due to the scorched-earth operation during Jeju 4·3. It was the first coverage of their stories by a local broadcasting station.

“Jeju 4·3 Special Report – Memories of the Land” covers the stories of those who not just lost their loved ones but were also deprived of the land where they had lived for generations, due to the scorched-earth operation during Jeju 4·3. It was the first coverage of their stories by a local broadcasting station.

The “newsmentary” report, combining the formats of news and documentary, highlights those villages that were burnt down or ruined due to the eviction order and the scorched-earth operation, the damage caused especially concerning the ownership of the land, the subsequent efforts to restore ownership by the victims’ descendants, and the need for relevant institutional improvements.

The KCTV Jeju reporting unit (Kim Yong-min, Kim Yong-won, and Moon Su-hee) said in their acceptance speech that they feel empathy for the victims and their families who were unlawfully dispossessed of their homes. According to the Grand Prize winners, their report was planned with high hopes of raising awareness of the need to investigate the property and material damage due to Jeju 4·3. “We consider our winning the Grand Prize as a call for continued attention to Jeju 4·3, rather than a simple accolade for our work,” they said, expressing gratitude for winning the 1st Jeju 4·3 Journalist Awards. Concluding their remarks, the journalists pledged that they will keep working to help resolve Jeju 4·3, meeting the expectations for the role of local media.

** The Grand Prize-winning report and the KCTV reporting unit giving the acceptance speech.

** The Grand Prize-winning report and the KCTV reporting unit giving the acceptance speech.

■ Excellence Award (Newspaper/Publication): “Special Coverage: The 70th Anniversary of Jeju 4·3 – Asking Camellias”, The Hankyoreh

The Hankyoreh released “Special Coverage: The 70th Anniversary of Jeju 4·3 – Asking Camellias” in a series of 65 articles in Korean, English, Japanese, and Chinese, both in the newspaper and on the internet.

The Hankyoreh released “Special Coverage: The 70th Anniversary of Jeju 4·3 – Asking Camellias” in a series of 65 articles in Korean, English, Japanese, and Chinese, both in the newspaper and on the internet.

This long series report had not been attempted by any other central media outlet. Part 1 of the report focused on revealing the truth, present, and future of Jeju 4·3, while Part 2 interpreted the revealed truth from a current perspective through various interviews with those who directly and indirectly experienced Jeju 4·3.

Specifically, the articles covered the causes and background of Jeju 4·3, the diaspora of those who migrated to Japan in avoidance of the turmoil, the ongoing retrials of those who were unlawfully convicted and served prison terms, and the efforts to clarify the responsibility of the United States.

Huh Ho-joon, the author of the mass-scale series report, said, “Every time I interview a victim or a victim’s family, it reminds me of the responsibility of media because their deep-rooted sorrow and the true nature of Jeju 4·3 have not been fully understood.” Thanking his colleagues at The Hankyoreh who steadfastly supported him through input and assistance in translation, Huh anticipated that the Jeju 4·3 Journalism Awards will provide great impetus to reporters and help uplift the value of peace, human rights, democracy, and justice.

** The Excellence Award-winning report (for the newspaper/publication category) and journalist Huh Ho-joon giving the acceptance speech.

■ Excellence Award (Broadcasting/Film): “Investigation K Trilogy: Jeju 4·3 and Fabricated Spy Cases – Memories That Fade”, KBS Jeju

■ Excellence Award (Broadcasting/Film): “Investigation K Trilogy: Jeju 4·3 and Fabricated Spy Cases – Memories That Fade”, KBS Jeju

“Investigation K Trilogy: Jeju 4·3 and Fabricated Spy Cases – Memories That Fade,” by KBS Jeju, identified the correlation between Jeju 4·3 and fabricated espionage cases, calling for public attention to the need for reflection on the past wrongdoings and for monitoring on a continued basis. The content covers the story of a man that made headlines on various media platforms, where his exoneration was confirmed in retrial 43 years after he was convicted for acts of espionage by disguising himself as a Korean-Japanese businessman. In the trilogy, the KBS Jeju reporting unit revealed that 30% of the nation’s fabricated espionage cases targeted those who were born and raised in Jeju. The reporters also interviewed judges and prosecutors that were once involved in fabricating North Korean spy cases, asking if they are willing to apologize to the victims. It is noticeable that the special report was followed by responsive measures and institutional improvements. Winning the Excellence Award, the KBS Jeju reporting unt (Bu Su-hong, Kang Jae-yoon, Na Jong-hoon, and Shin Ik-hwan) recalled how they felt producing the report. “It was regretful that the news on the espionage cases gained the media spotlight while the news on the belated exoneration of the falsely accused spy was considered insignificant.” According to the broadcasting team, their report led to the enactment of the nation’s first municipal ordinance specifying the provision of support for the victims of fabricated espionage cases, as well as the onset of relevant investigation. “We will always work to remember and record the truth so as to prevent the painful history from recurring,” they added.

** The Excellence Award-winning report (for the broadcasting/film category) and the KBS reporting unit giving the acceptance speech.

** The Rookie Award-winning report and journalist Kim Hyeon-kyeong giving the acceptance speech.

** The Rookie Award-winning report and journalist Kim Hyeon-kyeong giving the acceptance speech.

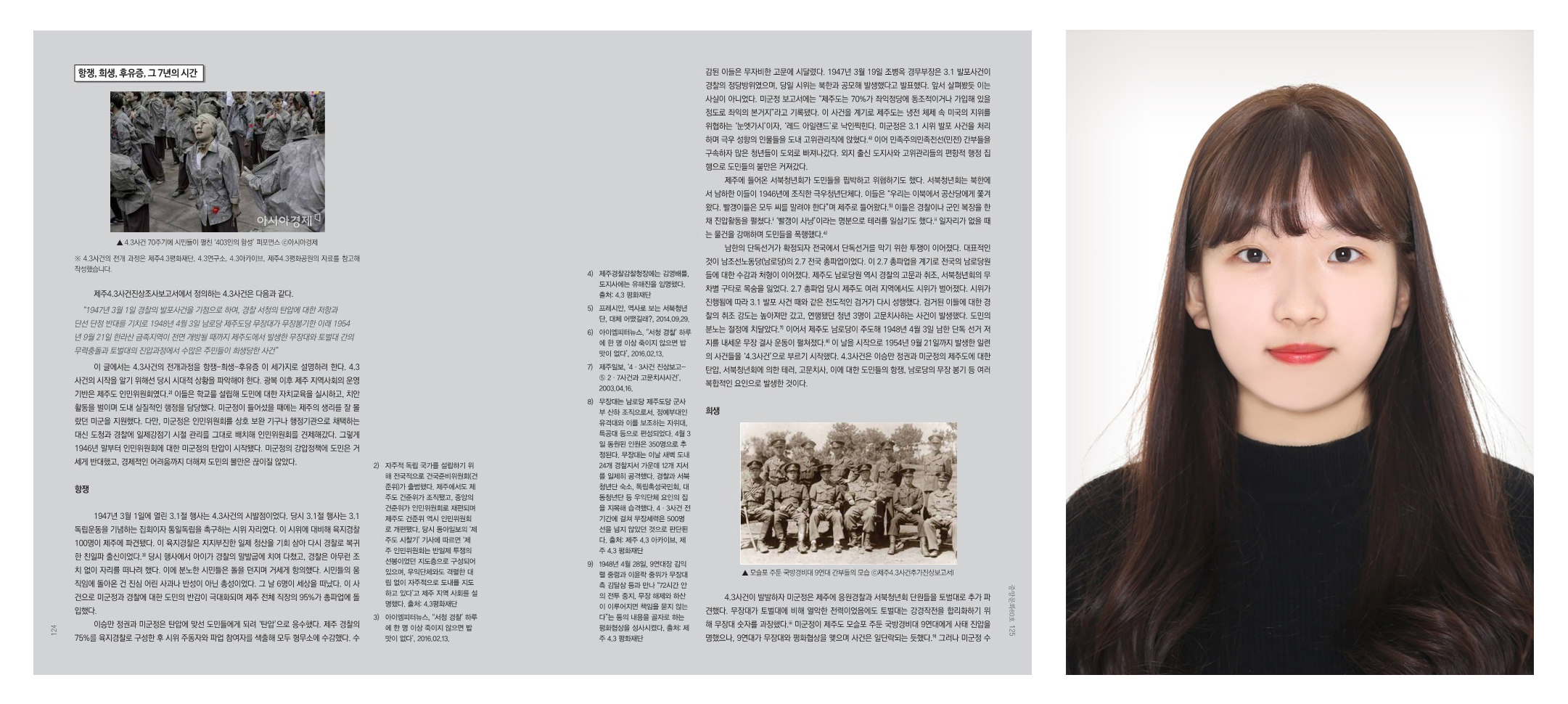

■ Rookie Award: “Recalling Jeju 4·3 with the Revised Bill on Jeju 4·3 Special Act”, Chung-Ang University Magazine “Chung-Ang Culture”

The Chung-Ang Culture, the official magazine of Chung-Ang University, published an article titled “Recalling Jeju 4·3 with the Revised Bill on the Jeju 4·3 Special Act”, winning the Rookie Award. The article contained nine photos of Jeju 4·3 reporting footage, which specially covered the topics of state violence, retrials of unlawful convicts, and female victims. Kim Hyeon-kyeong, the Jeju-born author, shared her personal experiences as a victim’s descendant and divided the seven-year-long period of Jeju 4·3 into three stages: the resistance, the killings, and the aftereffects. Positive changes were also addressed that are expected to follow the revision of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act. Additionally, the article pointed out the limitations of resolving the Jeju 4·3 issues, such as the difficulties holding the United States Army Military Government responsible for counterinsurgency operations and the unrecorded damage to those women who fell victim to the brutal acts committed during Jeju 4·3. According to the report, the case of resolving Jeju 4·3 can serve as a precedent for other similar events and help build peace and trust in Korean society.

During the acceptance speech, Kim said that she had long wished to cover the topic of Jeju 4·3 if given a chance. She also expressed her pleasure at winning the award, learning that her article meant something significant. “It is my wish that we will move one step closer to the resolution of Jeju 4·3 in the true sense so that it can become a hopeful precedent for other unresolved events of the past,” she concluded.

To select the winners, the 1st Jeju 4·3 Journalism Awards reviewed the media content on Jeju 4·3 that was released for the time span of four years from Jan. 1, 2018, to Dec. 31, 2021. A total of 29 nominees included nine articles for the Newspaper/Publication category, 15 shows for the Broadcasting/Film category, and five reports released by university papers and magazines. The nominated works met the high standards of the inaugural event and even featured emerging media content. Individual and group applicants also included promising undergraduate journalists that can contribute to passing down the values of Jeju 4·3 to the coming generations. The Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation will receive applications for the Jeju 4·3 Journalism Awards and announce the winners on a biannual basis.

A shift from the taxidermied memories toward the present memories

A shift from the taxidermied memories toward the present memories

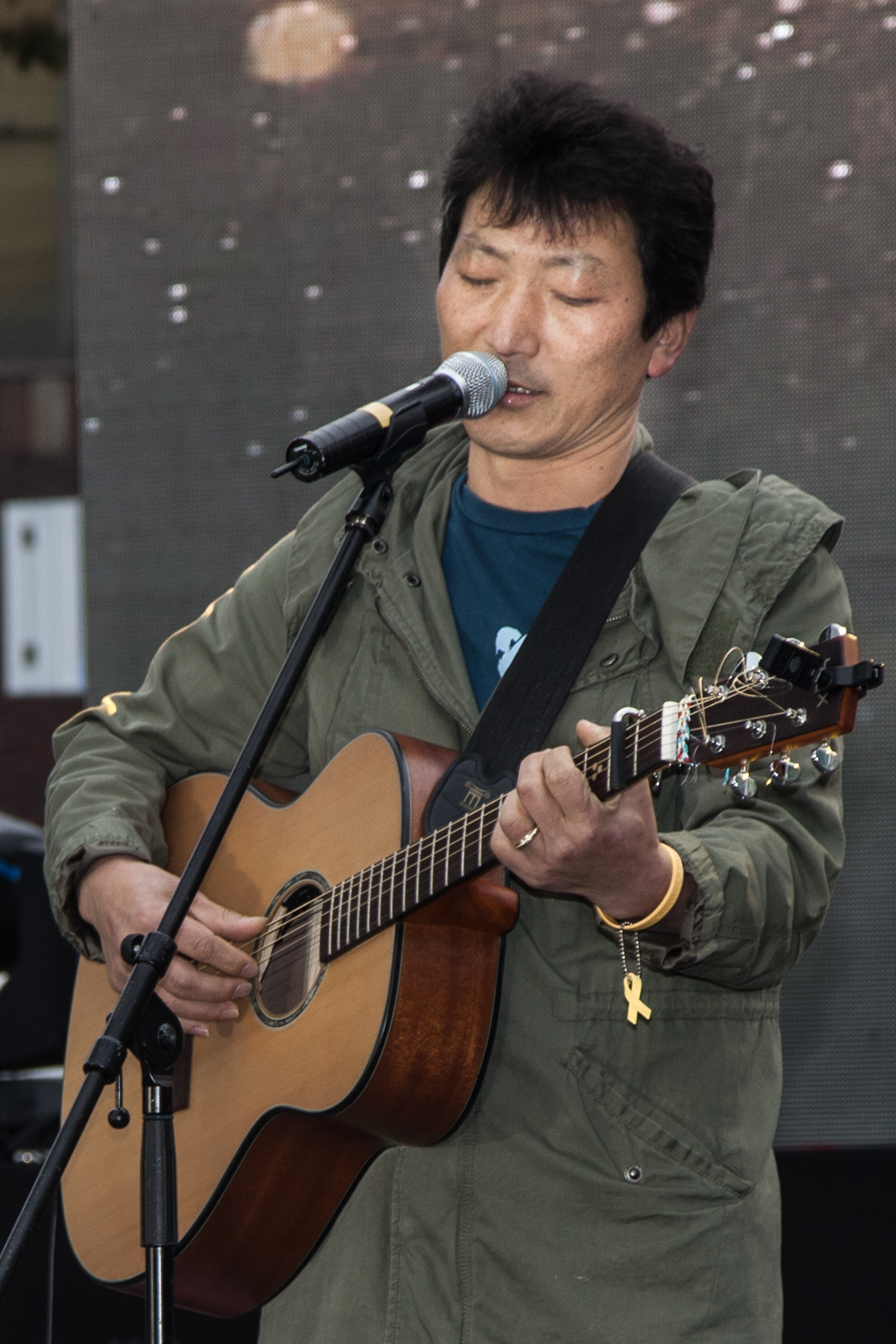

[Choi in the middle of the interview. The singer maintains seriousness as long as the talk is about Jeju 4·3.]

[Choi in the middle of the interview. The singer maintains seriousness as long as the talk is about Jeju 4·3.]