The Island Proud of its Spiritual Song

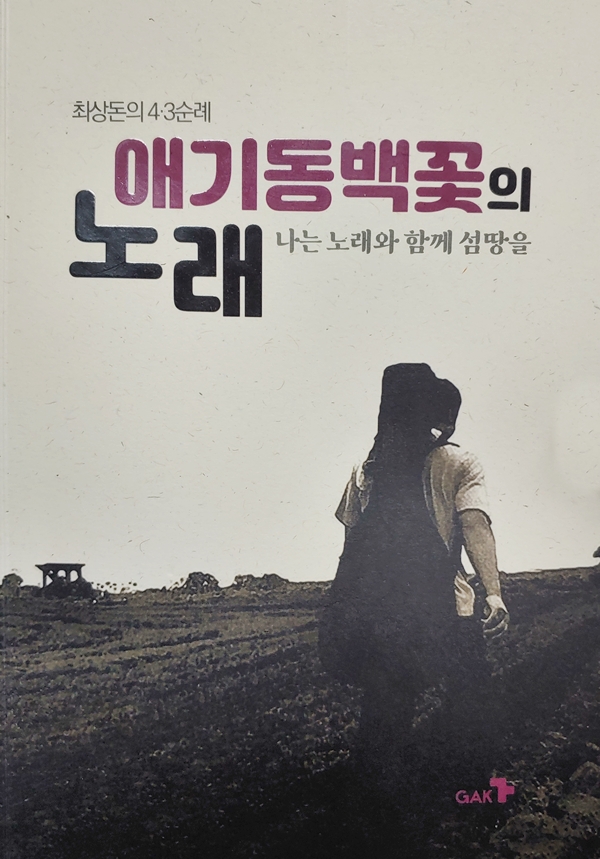

Book Review: Choi Sang-don’s Jeju 4·3 Pilgrimage, The Song of Baby Camellia

The Island Proud of its Spiritual Song

Kim Dong-yoon

Professor at Jeju National University, Literary critic

++ Published by Gak, 20,000 won.

++ Published by Gak, 20,000 won.

A song that embodies the island

The story of a series of Jeju 4·3 pilgrimages titled The Song of Baby Camellia – I Walk the Island with Songs, written by the singer Choi Sang-don, was finally published by Gak, a publishing company. I am glad to hear the news, as I joined a few of the singer’s pilgrimages, which have occurred nearly 100 times since 2006.

Reading the book brings back memories. It makes me feel as if I have joined every pilgrimage he has organized so far. It is like listening to Choi’s songs with guitar riffs while venturing to the corners of the island. Choi’s songs are wild and enchanting. His voice delivers resentment, yet it contains a dynamic feature. His belief is reflected in his songs and in his statement, “I want to be able to sing the song the island sings, to embrace the wounds of the island, to be proud of what the island possesses, to become closer to the island, and to become the island itself” (page 10).

Vivid moments of the pilgrimage

The first song written in the book is “The Song of Baby Camellia,” which starts with “When white snow falls on the mountain / the red flowers bloom on the field.” For me, this is the best song representing Jeju 4·3. The song reflects the sentiment and the stories about Jeju 4·3. It describes the camellia and azalea flowers, which symbolize the incident, and it is easy to sing. That’s why the song has been loved by the victims, their families, and the people of Jeju for some 20 years. The song is a masterpiece even more remarkable than “The Sleepless Southern Island.” I think the song should be designated as the official anthem of the Jeju 4·3 Commemoration Ceremony. In the prologue, Choi says he wrote the song thinking of the camellia flowers that bloomed at the peak of ‘Geombonangchi,’ a hill in his hometown of Cheongsu-ri, Hankyeong-myeon.

The content of the book is arranged by season and month, ranging from January with Bukchon-ri to December with the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park. Wherever there was a Jeju 4·3 site, he went on a pilgrimage.

++ Choi’s jacket, bought in 2006 before the pilgrimage, and the pilgrimage group passing the underpass near Mudeungiwat.

His pilgrimage goes on in Sambatjuseok, Mudeungiwat, Neobeunbat, Bihakdongsan, Altteureu, Jeongtteureu, Baekjoilson Cemetery, Manbengdi, Soknaengigol, Youngmowon Memorial Park, Marado Island, Hwangsapyeong, Hwabukcheon Stream, Sanjicheon Stream, Wonmul Oreum, Byeoldobong Peak, Eoseungsaeng Oreum, Bagumji Oreum, Seodal Oreum, Moksimulgul Cave, Keunneolgwe Cave, Darangshigul Cave, the prisons in Mokpo, Daejeon, and Daegu, as well as Kyoto and Osaka in Japan.

Choi’s notes, including “Gobeulak in Bukchon”, “Neobeunsungi in Bukchon”, “The Song of Heonmyo” (“Heonmyo” referring to an empty grave), “The Time of Hwabukcheon Stream”, “The Elegy of Byeoldobong Peak”, “The Lullaby of Moksimulgul Cave”, “Sanjicheon Stream”, “Your Olle” (“Olle” referring to a neighborhood street), “Jangdu” (“Jangdu” referring to the leaders of Jeju-based uprisings, “The Sorrow of Seodal Oreum”, “The Testimony – Baekjoilson Cemetery” (“Baekjoilson” referring to the descendants of the victims of killings in Sangmo-ri, Seogwipo), “Promise – The Song of Sanjeon” (“Sanjeon” referring to the mountain base of Jeju 4·3 resistance forces), “The Yellow Cactus – Lady Jin A-young”, “Hometown – The Village of Darangshi”, “Youngmowon Memorial Park”, “You – The Wind Blowing in the Prison”, “The Jeongtteureu Airfield”, “At Hannae Stream”, “Oh, Mt. Halla”, “The Time”, and “Highland Crysanthemum” are about all areas of the island.

Because he searched every corner of the island, the pilgrimage yielded significant results in finding the scenes of fading history.

When people who went up the mountain in objection to the one-sided election of May 10, 1948, were coming down from the mountain on May 12, 1948, the scene was photographed by a US Forces filming unit. While the picture is known to many of us, no one knows precisely where the photo was taken. Choi, on his pilgrimage, found evidence that the scene was taken near Neobeunbat, which is now Haean-dong, Jeju-si looking at Eoseungsaeng Oreum from afar (page 117).

He also found details that have yet to be uncovered. One of the examples was the Monument of the Liberation of the Korean People, the establishment of which was funded by the graduates of Daejeong Public Elementary School over a period of five years. The teachings of an unknown teacher moved the students at the time. The monument conveys the spirit of the Jeju 4·3 Resistance: “It is truly joyful that the people of Korea are now liberated from the grasp of Imperial Japan! Hence, we celebrate our liberation with overflowing delight and set up this monument” (page 169).

In pursuit of the dignified spirit of Jeju 4·3

++ Choi Sang-don singing the song, “Lee Jae-su – Jangdu”, in front of the grave of Lee Jae-su’s mother.

In February 2006, right before the beginning of the pilgrimage, the singer bought a windbreaker that would come to symbolize his consciousness (page 10). He has worn it for over 15 years. The color of the jacket is faded now, making us think of both the exhaustion he experienced during the pilgrimage and his integrity regarding Jeju 4·3.

The final path of pilgrimage in the book is “Lee Deok-gu’s Sanjeon”. He traversed the fields in the mountains from the entrance of Muljangori Oreum to Bulgeun Oreum near the Namjo-ro road. It was “a precious and long walk, such that I loaded my fatigued body on the bus long after sunset.” From this final pilgrimage, I found out what Choi’s version of the spirit of Jeju 4·3 is. It is to make Jeju 4·3 into a resistance of ordinary people who yearn for the unification and independence of Korea.

“Going on a pilgrimage is to meet our history. It means meeting the people who lived through that history. It is to examine the dreams they had. We should check whether their dreams or their historic value are being passed on. They may have had a better view of history than we do now. By remembering the deaths of at least 30,000 people, they regain their honor. They should be proud of themselves, as they were rightful. Regaining honor will lead to honoring the entire island … Now this path will lead from the inside of Jeju to the land beyond the ocean – Osaka, North Gando (or Jiandao in Chinese), and Taiwan. The revival of memories and the history recalled is for regaining honor. My companions in my pilgrimage will travel through time, walking the path of the chrysanthemum” (page 316).

Choi believes the honor of the people of Jeju can be recovered only when Jeju 4·3 is transcended: from victimization and commemoration into resistance. This is why he will continue the pilgrimage. The voyage will continue with his songs beyond the island of Jeju to East Asia and the world.

“In spring, the azalea blooms in the mountains and fields.”

++ In the schoolyard of Bukchon Elementary School.

++ In the schoolyard of Bukchon Elementary School.

While the book contains the precious memories of Choi’s travel, some flaws exist. It would have been better for the writer to prepare a map of the pilgrimage and to provide an index for crucial places. His writing uses honorific expressions, but there are some parts where informal expressions make sudden appearances. I do not think there is a fixed standard for selecting the style. The book could have used more thorough editing.

Lastly, for the readers to fully understand the value of this book, numerous songs by Choi Sang-don should be provided. Some pieces are published on CD, and some are available on streaming services. But all of them could be of better quality, as the recordings are crude. I hope the songs will be re-released soon with good quality. That way, “The Song of Baby Camellia” will move the world with its profound message.

“When the baby camellia falls, the winter passes/In spring the azalea blooms in the mountains and fields/As the colorful autumn leaves fall, and the season passes/The winter comes for the baby camellia.”

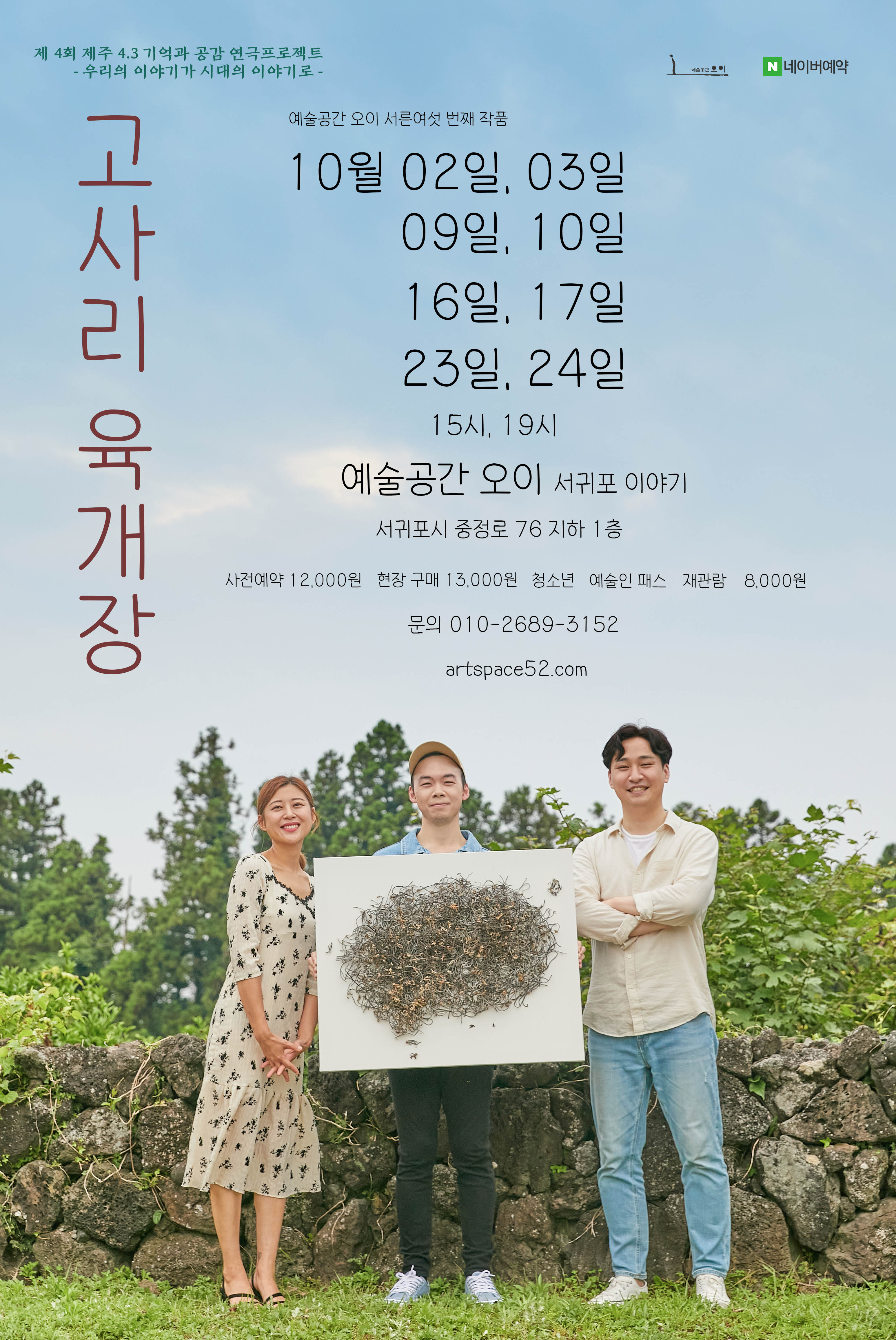

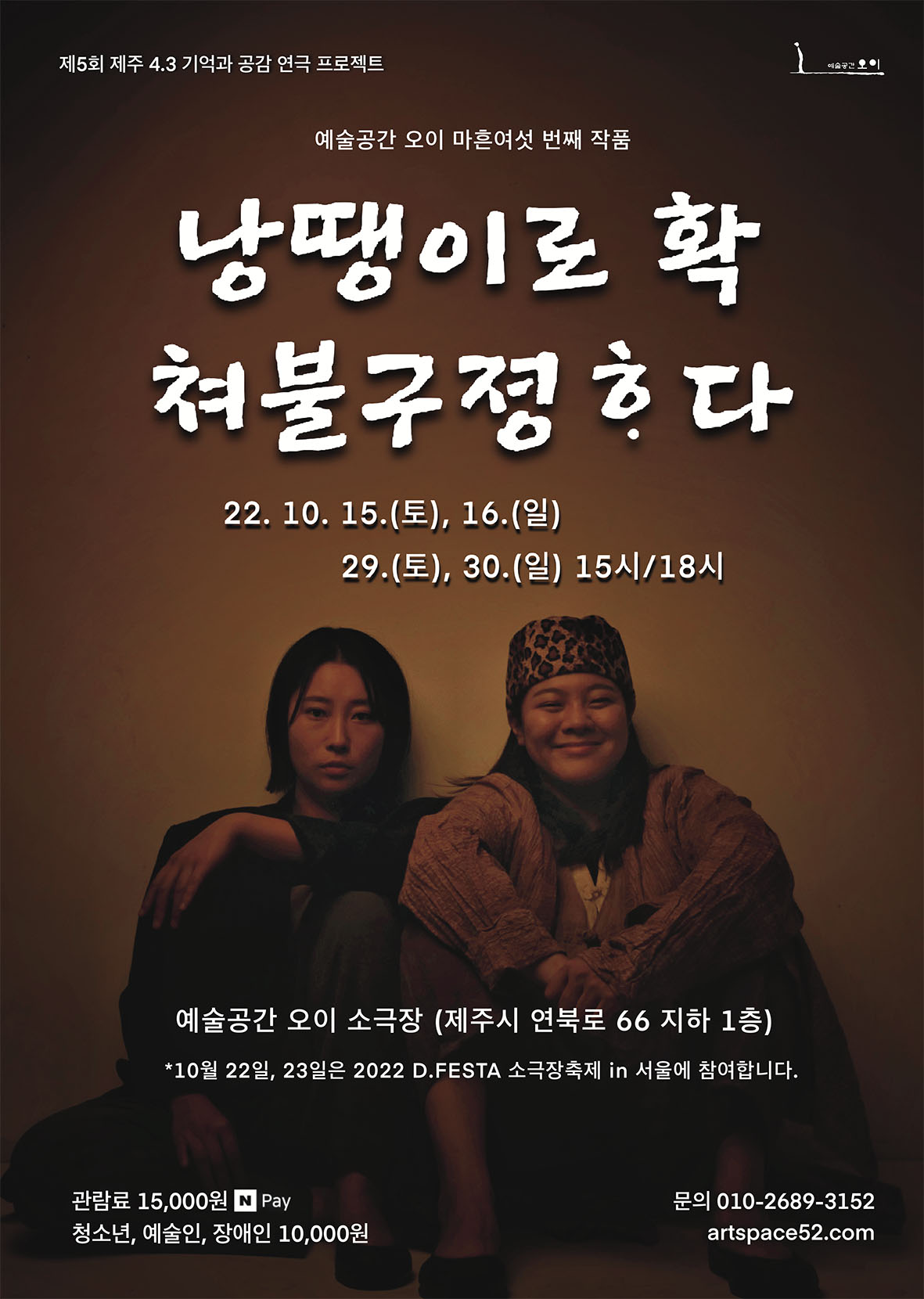

++ A small concert is held in the café of Art Space 52.

++ A small concert is held in the café of Art Space 52. ++ A group photo of members in 2016.

++ A group photo of members in 2016.

++ (From top to bottom) Current auditorium, practice room, and Culture Café.

++ (From top to bottom) Current auditorium, practice room, and Culture Café.

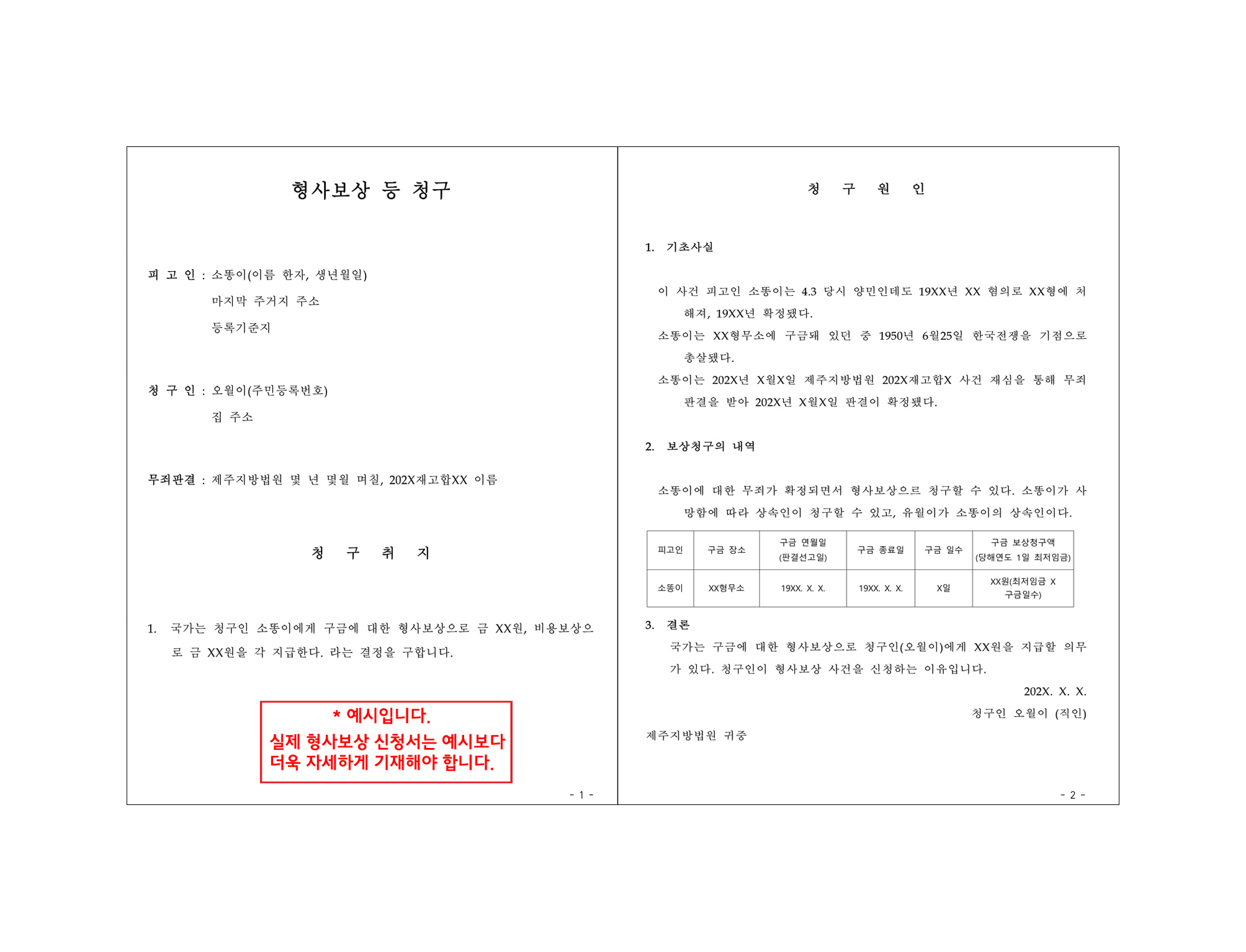

++ A retrial is held for surviving Jeju 4·3 victims of unlawful conviction at the Jeju District Court. (Photo provided by Jeju Special Self-Governing Province)

++ A retrial is held for surviving Jeju 4·3 victims of unlawful conviction at the Jeju District Court. (Photo provided by Jeju Special Self-Governing Province)

++ Park Hwa-choon (aged 95) is acquitted by the court on Dec. 6, 2022 after the retrial for her imprisonment 74 years ago due to the brutal torture by constabulary forces and the subsequent unlawful court-martial. (Photo provided by Jeju Special Self-Governing Province)

++ Park Hwa-choon (aged 95) is acquitted by the court on Dec. 6, 2022 after the retrial for her imprisonment 74 years ago due to the brutal torture by constabulary forces and the subsequent unlawful court-martial. (Photo provided by Jeju Special Self-Governing Province)