Achievements and Contributions – Photographer Kim Ki-sam

As a photographer, it is my duty to take photos of Jeju 4·3 movement

My job is to document and deliver the records

Interview and Arrangement by Jang Yoon-sik, Head of the Memorial Project Team

Photographs by the Editing Office and Photographer Kim Ki-sam

Photographer Kim Ki-sam is a living witness to the photographic record of the movement to discover the truth about Jeju 4·3. He was present at the most symbolic scenes of the movement, including the 1989 Jeju 4·3 Memorial Ceremony, which was the first public rally for the truth about Jeju 4·3 held in Jeju. He also recorded the discovery of the massacre site in the Darangshi Cave, rallies and protests by college students, and the activities of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute. The photographer, who has been documenting the truth-finding movement for more than 30 years, told us stories related to his photographs. Listening to his commentaries allows for a revisit to the importance of documentary heritage, as the Jeju 4·3 documents are expected to be inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World List. <Editor>

Photographer Kim Ki-sam is a living witness to the photographic record of the movement to discover the truth about Jeju 4·3. He was present at the most symbolic scenes of the movement, including the 1989 Jeju 4·3 Memorial Ceremony, which was the first public rally for the truth about Jeju 4·3 held in Jeju. He also recorded the discovery of the massacre site in the Darangshi Cave, rallies and protests by college students, and the activities of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute. The photographer, who has been documenting the truth-finding movement for more than 30 years, told us stories related to his photographs. Listening to his commentaries allows for a revisit to the importance of documentary heritage, as the Jeju 4·3 documents are expected to be inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World List. <Editor>

Kim Ki-sam

Kim returned to Korea in 1985, 11 years after he left for Japan. When the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute was established, he shared its office and naturally became a member of the institute, serving as an editorial board member. With a camera in his hand, he takes on the role of documenting all activities related to Jeju 4·3 at the institute.

Kim has always carried his camera to the scenes of the Jeju 4·3 movement.

Born in 1956 in Pyeongdae-ri, Gujwa-eup, Jeju Province, Kim worked at the Public Affairs Office of the Jeju Special Self-Governing Provincial Council from 1992 to 2016. Currently, he is a member of the Tamra Photographers’ Association. He has held solo exhibitions, including “I Cried a Lot Looking at the Moon” (1999, Photo Gallery Nature Love), “A Photographic Overview of the Jeju 4·3 Truth Revelation Movement” (2013, Sinsan Gallery), and “Truth Revelation Movement” (2024, Jeju National University Museum), and participated in many other exhibitions, including the “Jeju Camera Club Exhibition” and the “Tamra Photographers’ Association Exhibition.”

Books I Cried a Lot Looking at the Moon (1999), An Elegy of Darangshi Cave (co-author, 2002), A Photographic Overview of Jeju 4·3 Truth Revelation Movement (2013), Shamanic Ritual “Gut” at Dongbok Village’s Bonhyangdang Shrine (2016), A Heaven of Birds (photos included) (2018), A Hawk Flying Over the Jeju Seas (co-author, 2020)

When did you get started with photography?

My first exposure to photography was when I was living in Japan. There, I learned photography and was particularly interested in documentary photography, which suited my aptitude. From the beginning, I had a sense of duty to take pictures as a record.

I read a lot of books by Japanese photographers, and I was very impressed by W. Eugene Smith, who authored a book of photographs showing victims of mercury poisoning in Japan. It was the moment when I further realized the importance of documentary photography. I became increasingly fascinated with photography and was even accepted into the Japan Institute of Photography and Film in Osaka. But I was unable to attend due to financial reasons.

This is the first time I confess this, but I lived an undocumented immigrant in Japan for 11 years. Back then, a lot of Jeju Islanders stayed in Japan illegally. If caught, they were put in the Omura Immigration Detention Center in Kyushu. And when the plane was full, they were deported to Busan by boat.

Living in Japan, I heard that my mother was in a critical condition and thought, “I can’t help it. I have to see her. Or I will regret it for the rest of my life.” We are of six kids, and I’m the youngest. My mother was 46 when I was born.

So, I reported myself that I was an illegal immigration, saying that I would leave the country at my own expense. But they sent me to the Omura Immigration Detention Center. I was forced to stay there for about a month or two, and then repatriated to Busan.

I came back to Jeju right away, and that was in December of 1986. Nov. 7 on the lunar calendar is the date when my mother passed away. She died a week after I returned to Jeju. I have no regrets about it because I could stand at her deathbed.

As I was in Japan illegally, I couldn’t do photography overtly. I only did it as a hobby in my spare time. I took pictures of young Japanese people called Takenoko, who were randomly dancing on the streets.

I also documented those who went to labor sites while staying illegally and Jeju Islanders who migrated to Japan. And I compiled those pictures into a book titled I Cried a Lot Looking at the Moon.

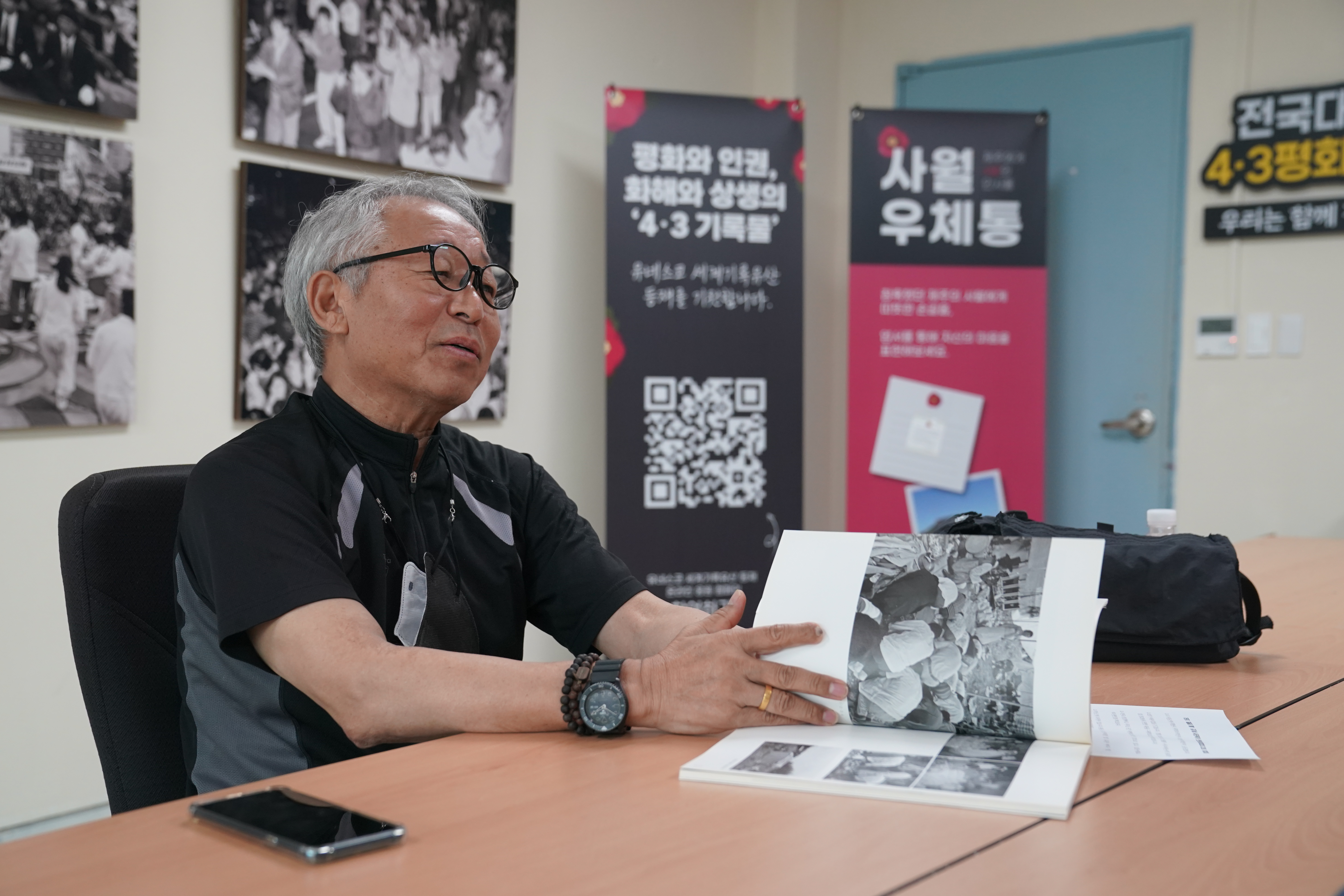

+++ Photographer Kim Ki-sam and Jang Yoon-sik, head of the Memorial Project Team, in conversation.

+++ Photographer Kim Ki-sam and Jang Yoon-sik, head of the Memorial Project Team, in conversation.

What inspired you to take photos of Jeju 4·3?

I came back to Jeju in 1985 after living in Japan for 11 years, and I gradually began my career as a photographer in Jeju in 1986. And in 1987, I met Mr. Moon Mu-byeong. At first, I did research on shamanic performances and shamanic shrines, not Jeju 4·3. We weren’t allowed to document and transcribe shamanic narratives openly at that time. While doing research on the shamanic rituals, I heard short stories about Jeju 4·3 told by local elderly people. As I didn’t have a car, I traveled around the province by bus.

One day, Mr. Moon rented a space on the second floor of a rice retail shop in Yongdam-dong, Jeju City, to create a research center for “gut,” shamanic rituals. The Jeju 4·3 Research Institute was opened in the very office, and I built a darkroom for photography in one corner. I still remember that the office, which had been a pool hall, had so many glue marks left on the floor to fix the pool tables. I sprayed water and scraped them all off with Mr. Hong Man-ki, the first secretary of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute.

My joining the Jeju 4·3 movement is closely related to the establishment of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute. The institute was opened on May 10, 1989, and naturally, I came to accompany the researchers on their events, research activities, and travels. I even took pictures of the opening ceremony of the institute. Later, I went on a research trip with Mr. Hong to publish a book titled “The Journey of Jeju 4·3.” I was the main photographer for the book, and that’s how I started taking Jeju 4·3 photos.

My joining the Jeju 4·3 movement is closely related to the establishment of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute. The institute was opened on May 10, 1989, and naturally, I came to accompany the researchers on their events, research activities, and travels. I even took pictures of the opening ceremony of the institute. Later, I went on a research trip with Mr. Hong to publish a book titled “The Journey of Jeju 4·3.” I was the main photographer for the book, and that’s how I started taking Jeju 4·3 photos.

In 1989, just before the institute was founded, the first memorial ceremony for the Jeju 4·3 victims was held on Jeju Island. I took pictures there, too, and that became a part of the documentary record. There were many other social issues that could be photographed, such as poetry exhibitions, yard theater performances, seminars, and rallies. Of course, I wasn’t allowed to freely take pictures of rallies at the time, but I tried whenever possible. My perception was that if there is something to record, it should be documented. “There should be someone to record it, and I’ll be the one to do the job. I have to be there on the scene,” I thought.

In the early days of the Jeju 4·3 movement, it must have been difficult to keep a photographic record. What were some of the challenges?

Once, Mr. Hong, secretary of the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute, said, “Hey, I have been tipped off that someone is coming to crack down on the institute.” It was a time when the intelligence agencies were under heavy surveillance. So, I went with Mr. Hong to get the research materials, take the film from the darkroom, and tried to hide them elsewhere. If I had left them at home, they might have come to my house, and there seemed to be nowhere to hide them. Finally, we came up with the idea of hiding about two rolls of film on top of the glass window at the back of the institute. I don’t remember if we hid the materials there or somewhere else. Anyways, I shudder to think that the photos could have been stolen. At the time, we were buying 30-feet rolls of self-developing film and cutting them up. The rolls of film, black and white film, could have been lost.

At the rally, it was common to be teargassed. I managed to get some toothpaste under my eyes to take pictures, just like college students, but I couldn’t resist it. It was so pungent that when rubbing my eyes with my hand, the pain was incredible. Some daily newspaper photographers were wearing gas masks, but I didn’t have one. At the rallies, you have to photoshoot from the police side to get a good shot of the row of students. So, the police back and forth swept me, and when I was on the police side of the rally, the police were taking photos of me. Of course, it was intimidating, but I didn’t care. I needed to document it. College students also acknowledged me because I often show up at rallies.

The police also investigated me when I was working for the Jeju Provincial Council. On how I started working for the provincial council, the fourth provincial council opened, and they didn’t have a photographer in the public affairs field. So, they asked for a recommendation from the Jeju branch of the Korean Photographers Association. I was recommended because I had had experiences in archival photography. After a background check and an interview, I was hired as a contractor.

At the time, I had no intention of belonging to any organization and taking pictures. I had no intention of living in Jeju, either. I came back from Japan for my mother, but as soon as I arrived, my mother passed away and I had to bury her. I thought, “Let’s leave as soon as I get a chance. If I can go to India for documentary photography, I’ll go.” So, I worked at a magazine for a while, shooting folklore, archiving the Jeju 4·3 movement, and then I started working for the Jeju Provincial Council. Until then, I thought it was just a day job, a part-time job.

Anyway, while I was in the provincial council, I was called to the Jeju police station twice. Somebody had reported me, asking, “Can someone who is so involved in the Jeju 4·3 movement work in the public office?” Once a report comes in, you cannot avoid investigation. I answered the police honestly. I had already taken pictures of Darangshi Cave. When they finished interrogating me, they handed over my statement and asked me to take handprints and fingerprints on it. I rejected. “How come taking pictures form a criminal act? I can’t do it,” I said. In the end, I left the police station without getting my handprints and fingerprints stamped.

After that, government employees wouldn’t let me near them, because they wouldn’t stay close to anyone who had been investigated by the police. I ate lunch alone. (Laughs) Looking back, I think they had the intention of firing me because I had been illegal in Japan for 11 years, had been detained in the Omura Immigration Detention Center, and had been taking Jeju 4·3 photos.

+++ The road in front of Jeju University is littered with Molotov cocktails and tear gas. Students at Jeju National University were the most militant actors in the fight for the truth about Jeju 4·3.

+++ The road in front of Jeju University is littered with Molotov cocktails and tear gas. Students at Jeju National University were the most militant actors in the fight for the truth about Jeju 4·3.

Honestly, the only thing that was harder than this was making a living. It was a time when film was very precious. And whenever I had money, I bought film, because film is the only way I could take pictures. My wife said, “Please take pictures that make money. It’s just pictures of caves all the time, of rallies. You always take pictures…” Ha ha. I still feel sorry for her.

You were always taking photos of the key scenes of the Jeju 4·3 movement. And the photo of Darangshi Cave is very significant in the history of revealing the truth about Jeju 4·3.

The photos of Darangshi Cave were not released until April 1992, but we first discovered the cave on Dec. 22, 1991. I joined the group of researchers including Kang Eun-suk, Kim Dong-man, and Kim Eun-hee at the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute to bring witness Moon Eun-cheol, who was from Darangshi Village and had been living in Sehwa Village

But it’s been so long that Moon couldn’t find the cave. So, the rest of us scattered around and looked for it. When we looked to Yongnuni Oreum, there were some big boulders that had collapsed. We thought that was the entrance. But when we went in, the dirt just fell out. We weren’t able to get in through that entrance. We came back the other way and found a little hole, like a badger burrow. I just stuck my head in there and shined a flashlight in there. There, I saw something white and shiny. It was the remains, and I was so stunned.

After discussing it on the spot, we agreed to come back another time and left for the day.

I didn’t have a car at the time, and the road to Darangshi Cave was too bad for a regular car. I asked a friend of mine, Yoon Sangpil, who was in my camera club, to drive me there. He had a jeep. We went back a few days later, just the original members, and that was the first time I went into Darangshi Cave.

Inside the cave, I took pictures, while Kim Eun-hee took videos with a camcorder. We worked on it at night as soon as we got back. When we developed the pictures, I was shocked to see how terrifying the scene was. But we couldn’t take them home, so we hung them in the darkroom. We didn’t make the announcement right away, either. I had an appointment to go to Japan to work on the book I Cried a Lot Looking at the Moon. In the meantime, we gathered experts, including journalists, lawyers, and doctors, investigated the case, and made an action plan. And finally, we released the photos in April 1992.

You’ve been taking pictures on the scenes of Jeju 4·3 movement for over 30 years now. How does that feel?

It used to be difficult to take pictures in an organized way because films were a scarce commodity. Now, the photography landscape has improved to the point where you can take a picture with a camera and save it as a computer file. This means you can have an organized photographic record.

Now the environment is better, but it’s a little disappointing that there are few people who are systematically recording. Maybe someone is working on it in some form, and I just don’t know it. But it’s very important to record and organize systematically. My idea is that records should be left in any form for 100 years, 200 years from now, for the history of the Jeju 4·3 movement to be remembered, however trivial it may look now. So I hope to see more people who are systematically recording the scenes.

Recently, I was asked to take photos for a disability grade evaluation of a victim suffering from a residual disorder. In many cases, the gunshot wounds are hard to be found on the body because 75 years have passed. This is why the evaluators rarely recognize those with gunshot wounds as Jeju 4·3 victims. In fact, the person’s life changed tremendously by the gunshot wound. It is heartbreaking whenever I come across a situation like that, and it reminds me of the importance of documentation.

I think I did my part to document the Jeju 4·3 scenes, so I have no regrets. I have never thought about making a fortune from photography. I used to buy film and documented the Jeju 4·3 movement even though I ran out of living expenses at home. There are some scenes that I missed, and I remember that it was from the Jeju 4·3 memorial ceremony in 1991. The memorial event that had been scheduled to be held in Jungang-ro was canceled due to a police blockade. So, we had a roadblock protest at night, throwing Molotov cocktails. It was very intense, and I took pictures of it. But I don’t have any pictures of the memorial service after that. It was held a few days after the protest, during the group tour of the historical sites in Songaksan Mountain.

I think I did my part to document the Jeju 4·3 scenes, so I have no regrets. I have never thought about making a fortune from photography. I used to buy film and documented the Jeju 4·3 movement even though I ran out of living expenses at home. There are some scenes that I missed, and I remember that it was from the Jeju 4·3 memorial ceremony in 1991. The memorial event that had been scheduled to be held in Jungang-ro was canceled due to a police blockade. So, we had a roadblock protest at night, throwing Molotov cocktails. It was very intense, and I took pictures of it. But I don’t have any pictures of the memorial service after that. It was held a few days after the protest, during the group tour of the historical sites in Songaksan Mountain.

But I wasn’t informed that there would be a memorial service in the mountain. Fortunately, someone else took a picture of it, but I regret that I didn’t get to see it myself.

In closing the interview, is there anything you’d like to say to young students who want to document Jeju 4·3 in photographs?

If the earlier activists who recorded the Jeju 4·3 movement were to organize the ‘scenes,’ I think a different approach is needed now. Recently, Ko Hyun Joo’s posthumous exhibition was held (June 23 to July 31, 2023, Jeju 4·3 Peace Memorial Hall). I was impressed by her perspective. I hope that there will continue to be those who try new approaches. We need to keep raising public awareness of Jeju 4·3 and pass the values on to young generations.

As a photographer, it is my duty to take pictures of the Jeju 4·3 movement. My job is to document and deliver the records. And I’ve documented and delivered the record within the broad boundaries, so I am satisfied with that.