Returning the Missing Victims to Their Families… Resolving Grievances

–

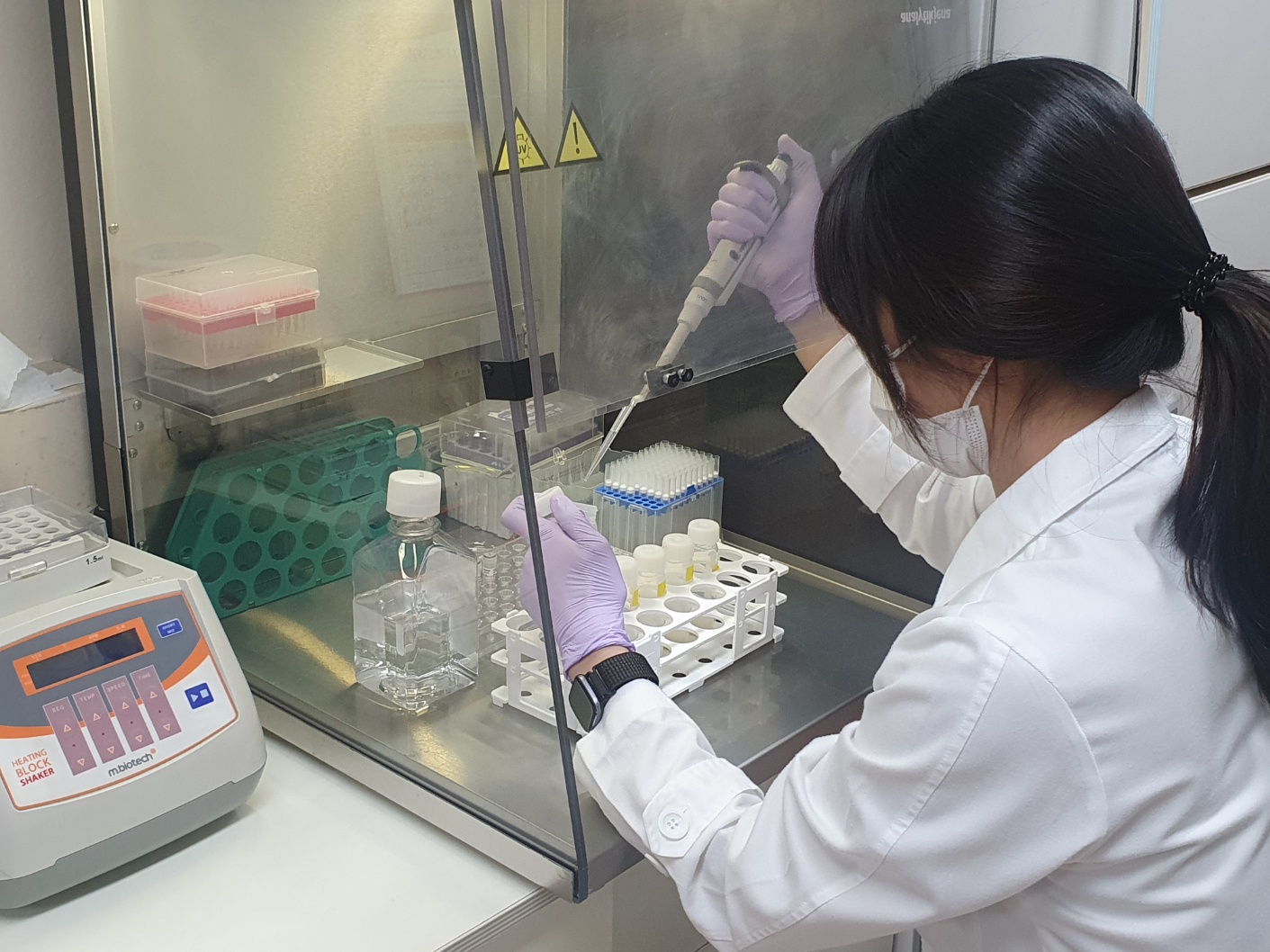

Identifying Jeju 4‧3 Victims Through DNA Analysis

- Blood Sampling is Key to Obtaining Meaningful DNA Data

Professors Lee Soong Deok and Cho Sohee

The project to excavate remains and identify Jeju 4‧3 victims began in 2007.

So far, 414 sets of remains have been recovered from sites including the current Jeju International Airport. Thanks to the active participation of bereaved families in blood sampling and the efforts of Seoul National University’s Forensic Medicine team, the identities of 144 individuals have been confirmed. Since 2018, the Seoul National University team has implemented advanced DNA analysis techniques, including Single

Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) and Short Tandem Repeat-Next Generation Sequencing (STR-NGS), enabling identification through blood samples from both maternal and paternal relatives as distant as 8th cousins. We spoke with Professors Lee Soong Deok and Cho Sohee from the Department of Forensic Medicine at Seoul National University College of Medicine, who are working to reunite missing Jeju 4‧3 victims with their families through DNA analysis.

- Editor’s Note

Interview Compiled by Yang Jeong-sim, Chief of Research and Investigation Office

You’ve been working for a long time to identify missing Jeju 4‧3 victims through DNA analysis, uncover the truth of Jeju 4‧3, and provide solace to bereaved families. What were your initial thoughts when you first began this project?

Professor Lee Soong Deok: Years ago, I was contacted by the Jeju 4‧3 Research Institute, asking me to give a lecture to help them understand the circumstances surrounding excavation of remains and DNA analysis, which I did. That was my first encounter with Jeju 4‧3, and I also had the chance to visit the excavation site inside the Japanese Cave Encampment on the coast of Byeoldobong Peak. One of the roles of forensic medicine is identifying people—determining their identities.

Honestly, when I was first asked to assist with the excavation and identification of Jeju 4‧3 victims, I didn’t fully grasp the significance of the event and initially thought of it as just another routine task. But after discussing the matter at the Jeju 4‧3 Research Institute, I realized it was far from routine and would involve some academic challenges. From the beginning, I felt it was crucial to carefully design the project to ensure its success.

Now, many of the challenges I initially thought would be difficult academically have been addressed by Professor Cho Sohee. The most critical aspect of DNA testing is having familial data—someone to compare it against. But there was no prior data available to identify the remains of the Jeju 4‧3 victims.

Another issue was that bone analysis at the time was one of the most challenging types of testing. Since obtaining results was so difficult, the task felt even more daunting. Additionally, because this work required a long-term perspective, I spent a great teal of time contemplating the best approach to take.

Between 2007 and 2009, we discovered 387 remains from a mass killing during Jeju 4‧3 at the current Jeju International Airport site, marking the beginning of full-scale DNA analysis. The early stages must have been quite challenging.

Between 2007 and 2009, we discovered 387 remains from a mass killing during Jeju 4‧3 at the current Jeju International Airport site, marking the beginning of full-scale DNA analysis. The early stages must have been quite challenging.

Professor Lee Soong Deok: At that time, the excavation was carried out collaboratively by Jeju National University’s Industry-Academic Cooperation Foundation and the Jeju 4‧3 Research Institute, which enabled large-scale DNA testing. As I mentioned earlier, while excavating remains is crucial, the most important factor is having information from the victims’ families for identification. That’s why I’ve always emphasized the need for blood sampling by the bereaved families, both then and now.

There were several reasons why I believed blood sampling was necessary. One was that the search process would take a very long time, and during that period, new testing methods we’re currently unaware of might be introduced. Relying solely on oral samples wouldn’t be sufficient. Another point, which might not be apparent to most people, is that the act of giving blood can serve as a form of ritual for the bereaved families. During the process, they share their stories, which can help release some of the emotional burdens they’ve carried for so long. Blood sampling takes time and can be painful, but thanks to the active participation of Jeju 4‧3 victims’ families, we’ve been able to identify 144 individuals.

Could you briefly explain the forensic identification process in a way that the general public can easily understand?

Professor Cho Sohee: The purpose of forensic genetic analysis is to identify individuals. When conducting tests for identification, DNA extraction from remains is much more challenging than extracting from live samples typically used in other tests. In the case of Jeju 4‧3 victims’ remains, they’ve been buried underground for a very long time and have suffered damage from bacteria and external factors, such as UV rays from sunlight. These external factors negatively impact the quality of DNA, which is why we need to exercise extra caution when extracting genetic material from remains. The extraction process itself takes a long time, and the amount of DNA we can obtain is often extremely limited.

Next comes the DNA analysis. As I mentioned earlier, extracting DNA from remains is challenging, but making comparisons is even more critical. The goal isn’t just to extract DNA from the remains―it’s to compare it with the DNA of relatives and derive meaningful information. That’s the primary purpose of the process.

We typically use methods such as analyzing paternal lineage, maternal lineage, and parent-child relationships through paternity tests. Relatives undergo the same tests, and the results are compared. When meaningful matches are found, we can confirm the identity of the remains.

As Professor Cho mentioned, analyzing remains that are over 70 years old must be very challenging. For instance, during the excavation in Gollyeonggol, Daejeon, 200 remains were discovered, but samples could only be taken from 70 of them. Similar issues were encountered with the Jeju International Airport remains. However, as Professor Lee pointed out, advances in DNA analysis techniques have recently allowed us to achieve better identification outcomes.

As Professor Cho mentioned, analyzing remains that are over 70 years old must be very challenging. For instance, during the excavation in Gollyeonggol, Daejeon, 200 remains were discovered, but samples could only be taken from 70 of them. Similar issues were encountered with the Jeju International Airport remains. However, as Professor Lee pointed out, advances in DNA analysis techniques have recently allowed us to achieve better identification outcomes.

Professor Lee Soong Deok: That’s correct. Technological advancements have made things that were previously difficult either possible or more likely to succeed. Let me use Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) as an example. As I mentioned earlier, the extent to which remains have been degraded by external factors significantly impacts test results. Due to these external factors, DNA often loses its original length, leaving us with shorter fragments or, in many cases, no viable results at all. However, the introduction of NGS has allowed us to derive results even from shortened DNA fragments, significantly increasing the amount of information we can obtain compared to before.

What’s encouraging is that terms like SNP and NGS, which are highly technical and typically used by researchers, are now being casually mentioned by the Governor of Jeju and those involved in Jeju 4‧3 projects. It’s personally gratifying to see these advances in testing technology gaining recognition and value. Currently, Jeju is leading the way in DNA analysis for resolving historical issues both domestically and internationally. This progress has only been possible through the collaboration of bereaved families’ associations, government officials, and civic organizations in Jeju.

We are always grateful that when we propose the use of SNP or NGS, the significance of these methods is understood and supported. Although the Jeju Special Self-Governing Province and related foundations share the same goals as we do, they are administrative bodies with procedural requirements that may not always align with our research process or outcomes. Their willingness to find compromises has been instrumental in making this work possible.

As a result of such efforts, we’ve been able to expand blood sampling from bereaved families every year, which has also allowed us to conduct DNA analysis more actively.

Professor Lee Soong Deok: The importance of blood sampling by families is exemplified by two cases this year where families were reunited with their lost relatives. The remains of the late Kang Moon-ho did not initially yield definitive results. However, many family members, including great-grandchildren, participated in blood sampling, making the identification possible. Another case involved President Lee Han-jin of the Association of Jeju People in America (New York), who provided a blood sample during a brief visit to Korea, enabling the identification of his brother’s remains.

When we review the DNA extraction results from the remains found at the airport, we see cases with very promising results where identification is still not possible, as well as cases with intermediate or poor result. For the latter, even multiple testing methods face limitations, requiring further research from experts like Dr. Cho to resolve them in the future. For the former, there is significant potential for identification using current methods, which is why extensive blood sampling from families is so crucial.

When you were first asked to take on this project, you must have approached it with the mindset of a forensic scientist. During an identification report meeting, Professor Lee, you once tearfully said, “I’m truly sorry for finding them so late.” Your sincerity was deeply felt. Over the course of this work, how has your perspective changed compared to when you first started?

When you were first asked to take on this project, you must have approached it with the mindset of a forensic scientist. During an identification report meeting, Professor Lee, you once tearfully said, “I’m truly sorry for finding them so late.” Your sincerity was deeply felt. Over the course of this work, how has your perspective changed compared to when you first started?

Professor Lee Soong Deok: I believe that the excavation and identification of remains are ways to help bereaved families resolve their long-held grievances. Whenever I visit the Jeju 4‧3 Peace Park, I make it a point to look at the Headstone Monument Engraved with Names of the Deceased and reflect on those who have yet to be found. It always weighs heavily on my heart and deepens my sense of responsibility for this work. I remember a time when Professor Cho and I were in Jeju and a bereaved family member who had just found her brother’s remains cried out, “Brother, why did you come so late?” She was overwhelmed with tears, and that moment stays with me. It’s moments like these that remind me of the importance of helping to ease their grief, however we can.

Professor Cho Sohee: I began participating in this project in 2014. At the time, I was still learning about forensic science, so I approached it primarily from an academic perspective. Later, as I became a primary researcher and experienced the identification-reporting sessions, my perspective changed significantly. I developed both a sense of mission and a deep sense of fulfillment through this work. Seeing the bereaved families reunited with their loved ones became a turning point for me. Now, when I see the names of the victims, they no longer feel like mere subjects of research—they feel like family.

Lastly, is there anything you’d like to say to the bereaved families?

Professor Lee Soong Deok: I hope they can find closure before they pass. While DNA sampling is important, I also hope they use this opportunity to share their stories and leave behind meaningful information. Many of our elders often think, “I must not pass my pain and sorrow onto my children.” However, the case of Jeju 4‧3 isn’t something that should be borne on an individual level. Since such tragedies could happen again, I believe it’s crucial to resolve and address this properly.

The successful participation of bereaved families in blood sampling ensures that the significance of this project is passed on to future generations. This project is not just about finding people; it’s an issue of trust between the state and its people. This work is ongoing, and while the details differ across periods, many issues share similar characteristics in nature. Projects like this should be comprehensively supported at the national level and approached with a long-term perspective. We must ensure that bereaved families do not pass away harboring unresolved grief and that even their descendants can eventually find their lost loved ones. To the bereaved families, I sincerely urge you not to carry that burden of sorrow alone.

Professor Cho Sohee: Since I’m deeply involved in DNA analysis, I know that the more bereaved families participate in blood sampling, the more evidence we have, and the greater our hope becomes. I believe this is a profoundly meaningful endeavor, and I am strongly driven by the desire to identify as many individuals as possible while their family members are still alive. I encourage families to participate in blood sampling.

The excavation and identification of Jeju 4‧3 victims are projects we are pursuing with the utmost sincerity. We are truly fortunate to have your support and guidance, as esteemed professors from Seoul National University’s Department of Forensic Medicine. We sincerely thank you.

Professor Lee Soong Deok: This is work that needs to continue for a long time. Similar incidents must not happen again. To prevent that, I believe it’s important to keep revisiting and reaffirming its significance. I see my role as connecting this work to the next generation, and I am committed to fulfilling that responsibility. I’m reassured knowing that Professor Cho, here with me, will carry on this work effectively.