Capturing Memories Through Photography

Photographer Kang Jeong-hyo

Photographer Kang Jeong-hyo

Interview and Compilation by Jang Yoon-sik, Memorial Project Team Leader

Documenting Jeju 4·3 requires deep affection and persistence. Photography, in particular, demands presence at the scene. Photographer Kang Jeong-hyo has long captured the shadows and lights of Jeju 4·3 through the expressions of bereaved families. His camera has consistently been present at sites of excavation of victims’ remains and investigation into the truth of Jeju 4·3. Additionally, Kang has raised awareness of Jeju 4·3 through the publication of photo books and exhibitions. He also co-chaired the Memorial Project Committee for the 70th Anniversary of Jeju 4·3. Here, we delve into his journey.

Documenting Jeju 4·3 requires deep affection and persistence. Photography, in particular, demands presence at the scene. Photographer Kang Jeong-hyo has long captured the shadows and lights of Jeju 4·3 through the expressions of bereaved families. His camera has consistently been present at sites of excavation of victims’ remains and investigation into the truth of Jeju 4·3. Additionally, Kang has raised awareness of Jeju 4·3 through the publication of photo books and exhibitions. He also co-chaired the Memorial Project Committee for the 70th Anniversary of Jeju 4·3. Here, we delve into his journey.

– Editor’s Note –

Kang Jeong-hyo’s Profile

Born in Jeju in 1965, Kang has worked as a journalist, photographer and mountaineer, and as a lecturer at Jeju National University. He has served as Chairman of the Jeju Federation of Cultural and Artistic Organizations and Co-Chairman of the Memorial Project Committee for the 70th Anniversary of Jeju 4·3.

Starting with 《Jeju Now》 (1991), Kang has published 10 personal works and numerous collaborative books covering Jeju’s nature, Jeju 4·3, mythology, history, and cultural heritage. His notable Jeju 4·3-related works include 《Bones and Gut》 (2008), 《Jeju 4·3 Literary Map Volumes I and II》 (2011, 2012), and 《The Land Departed by Jeju 4·3, Revisited by April 3》 (2013).

Since holding his first solo exhibition (Dongin Gallery) in 1987, Kang has hosted 16 solo exhibitions and numerous group exhibitions. Among these, his Jeju 4·3-related exhibitions include the following:

2016 〈Jeju 4·3, Those Left Behind〉, Mabui-gumi, Okinawa

2013 〈The Land Departed Due to Jeju 4·3, Revisited Due to Jeju 4·3〉, Jeju 4·3 Peace Park Exhibition Hall, Jeju

2004–2015 Jeju 4·3 Photo Exhibition, Jeju Culture and Art Center, Jeju

1994–1998 Jeju 4·3 Art Festival, Jeju Culture and Art Center and Sejong Gallery, Jeju

01: Jang Yoon-sik, Memorial Project Team Leader of the Jeju 4·3 Peace Foundation, and photographer Kang Jeong-hyo engage in a conversation at the artist’s studio, ‘Isojae.’

How did you first learn about Jeju 4·3?

When I was little, my family observed two ancestral rites on the same day—one for my maternal grandfather and the other for my paternal uncle. Because there were two ceremonies on the same day, the family would split up: my father and older brother would go to my uncle’s house, while my mother and I went to my grandfather’s. As a child, I thought it was a coincidence that they passed away on the same day. But I learned the truth when I entered college.

‘Ah, this was because of Jeju 4·3.’

I was part of Jeju National University’s class of 1984. At that time, it wasn’t easy to access anything about Jeju 4·3. The only thing available was Hyun Ki-young’s novel <Sun-I Samch’on>, which was briefly allowed on the market before being banned again. Back then, government agents were stationed on the first floor of the student union building.

But in 1987, the situation began to change. The Chun Doo-hwan regime was promoting university and education liberalization policies as a means to control campuses. However, following the national transition to democracy, a movement for genuine liberalization began emerging from within universities, significantly altering the atmosphere among students. Universities at the time became liberated zones. Students’ voices grew louder, and their creativity, especially in organizing protests, was remarkable.

It was during this period that a memorial altar for Jeju 4·3 victims was set up on campus for the first time, and wall posters calling for uncovering the truth about Jeju 4·3 were put up. Some students involved in these activities were arrested, prompting demands for their release and midterm exam boycotts. I believe this marked a turning point for the rapid spread of the truth-finding movement. I was head of reporting for Jeju National University’s newspaper, which is when I began to engage with Jeju 4·3 in earnest.

When did you start taking photographs seriously?

During my university years, I joined the school newspaper. The position of photojournalist was vacant, and someone asked if anyone could take photos. All I had was some experience handling a camera in high school, but I volunteered, saying, “I’ll do it.” That’s how my journey with photography began.

When I give lectures at universities, I always emphasize this experience to my students. I tell them: “I became a photojournalist simply because I had used a camera a few times before. With passion and commitment, I became a professional. You must have confidence in yourself because everything depends on how you approach it.”

Even when I joined a daily newspaper after graduation, I started as a general reporter, not a photojournalist. I passed the exam as a general reporter but later transitioned to photojournalism. Many people asked why I chose photojournalism, which they saw as more demanding. But a photojournalist can’t do their job without being on-site, and I loved going to the field. That’s why I made the switch. As a result, I naturally found myself present at the forefront of the Jeju 4·3 truth-seeking movement, documenting survivors and other stakeholders.

What message do you aim to convey through your Jeju 4·3 photographs?

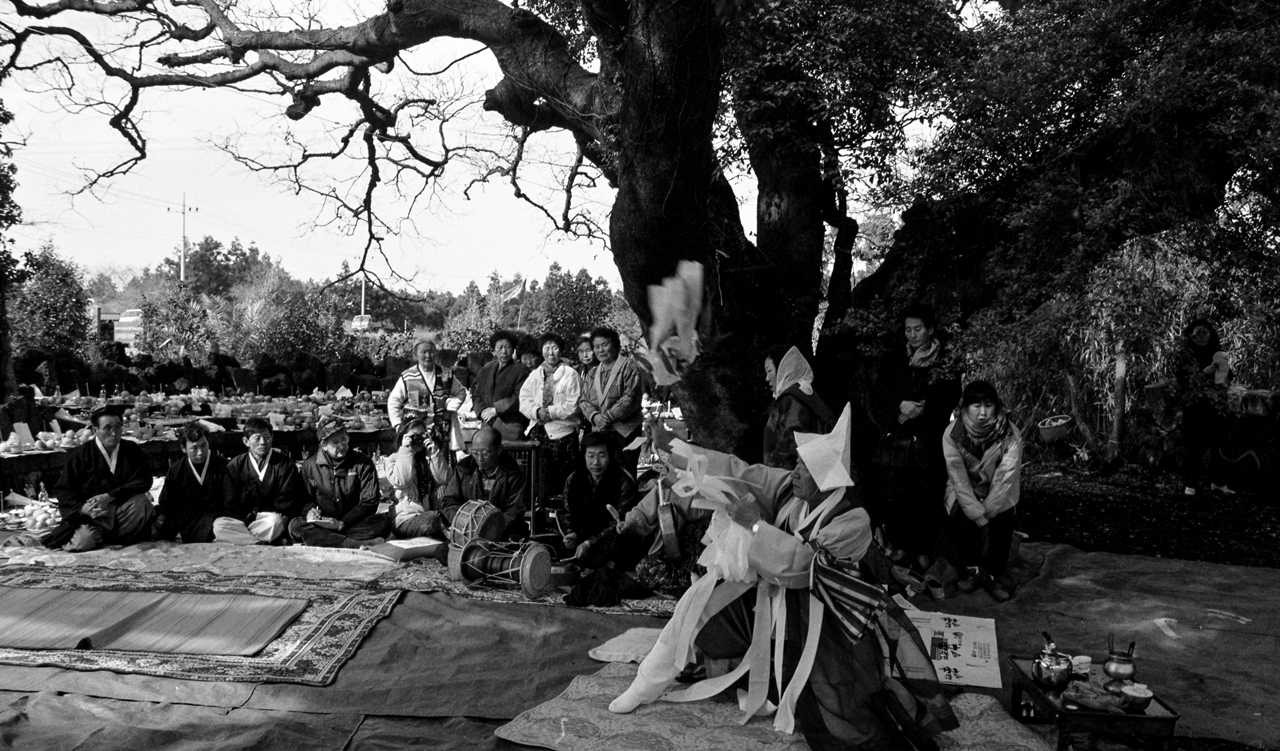

I began taking Jeju 4·3 photographs in earnest at the first Joint Memorial Tribute Ceremony in 1994. In the early days, the Jeju 4·3 memorial services were divided into the Memorial Tribute Ceremony by civic groups and the Soul Consolation Rite by the bereaved families’ association. The bereaved families’ association held their memorial event at Sinsan Neighborhood Park, while civic groups organized theirs at the Jeju Citizens’ Hall. Later, they were disallowed to use the said venues and selected other places, like Jeju Teachers College and Gwandeokjeong Square. But police intervened, leading to tear gas incidents. These separate memorial events merged into a single joint ceremony starting in 1994.

If you look at the photos taken during this process, you can see the changes in the expressions of the bereaved families, reflecting the evolving journey of uncovering the truth about Jeju 4·3. The shifts in their expressions are evident. In the early photos, they uniformly appear somber, heads bowed in sorrow. However, after the enactment of the Jeju 4·3 Special Act in 2000, their expressions became somewhat brighter. With the president’s attendance and official apology, the commemoration of the 70th anniversary of Jeju 4·3, and the recent decision on reparation for victims, their demeanor now feels markedly different.

My first photo, ‘The Years of Suffering—Silence’, which was part of the Capturing Jeju 4·3 exhibition at the Jeju 4·3 Peace Memorial Hall from March 25 until May 5 this year, also illustrates this well. This piece was first displayed at the 4th Jeju 4·3 Art Festival in 1997. It combines two photographs: one of bereaved families attending the 1994 Soul Consolation Service at Tapdong Square and another of ivy roots entwined around a stone wall. Through the bowed heads of the bereaved families and the tangled ivy roots, I sought to depict the silence they were forced to endure.

I believe that photojournalists must focus on two elements: memory and documentation. As photographers of the present, we have a responsibility to capture the current reality. With this sense of duty in mind, I photographed Jeju 4·3 while reflecting on the emotions of the bereaved families.

As a photographer, it’s a bit embarrassing to my profession to share, but something happened during the 1997 Soul Consolation Ceremony at the Jeju Sports Complex. In the crowd, there was a frail, elderly woman dressed in traditional Jeju clothes, with a white headscarf tied around her head. As she approached to inscribe a name on the memorial tablet, six or seven photographers swarmed around her, taking pictures. It was staged from the start. I was furious and started an argument. I felt that such methods couldn’t capture the genuine emotions or the decades of anguish etched on the faces of the bereaved.

Scene from the 48th Joint Soul Consolation Ceremony for Jeju 4·3 Victims held at Tapdong Square (ⒸKang Jeong-hyo)

The Years of Suffering—Silence (By Kang Jeong-hyo)

Could you share a particularly memorable project?

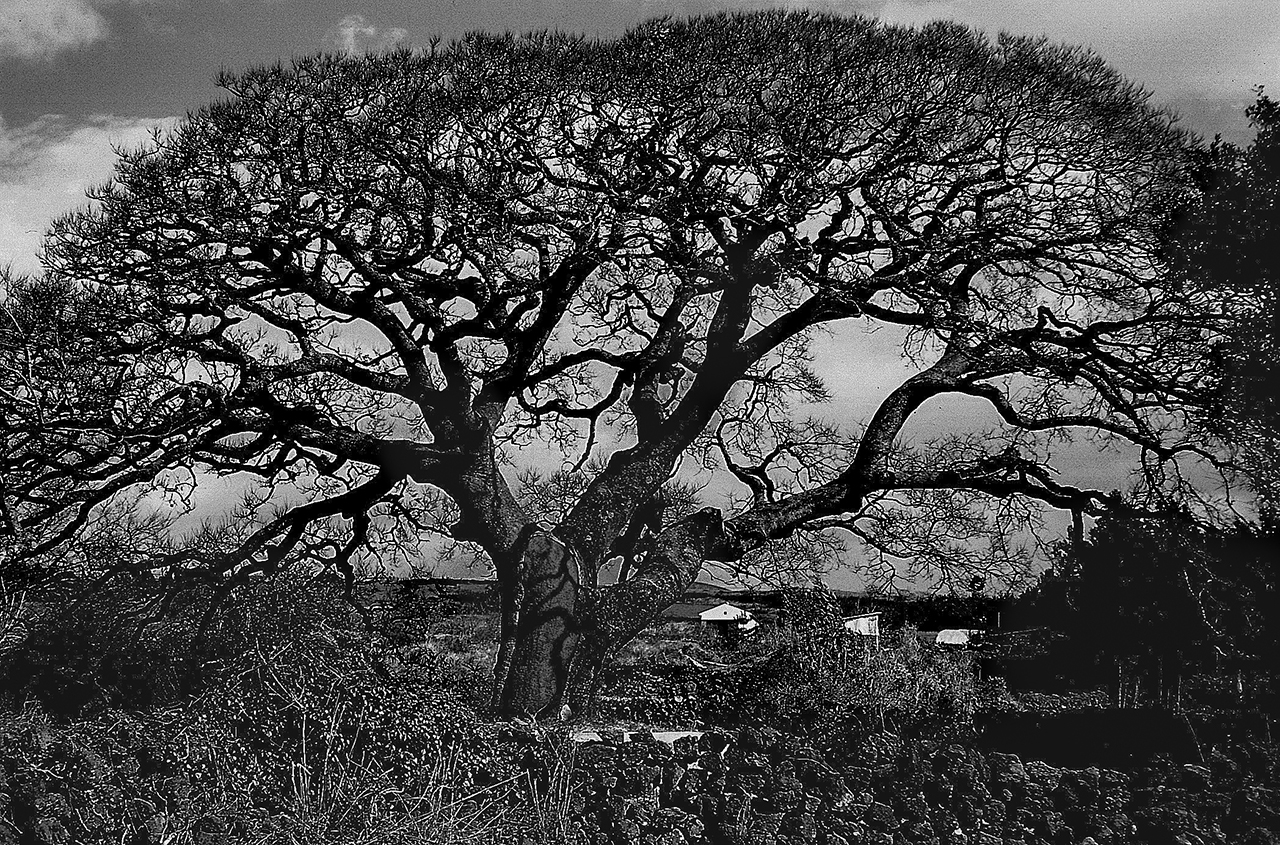

I believe the local hackberry trees silently bear witness to Jeju 4·3 and still testify to the fact that these places were sites of the tragedy. Known as pongnang in the Jeju dialect, these hackberry trees served as communal resting spots at the centers of villages. One of my photos features the hackberry tree in Dongbok Village. This tree stood in the center of the village and served as the initial gathering point on January 17, 1949, when 86 residents were taken to a place called gulwat and massacred. The villagers were assembled under that tree before being led away. In that sense, the hackberry tree is a silent witness to a horrific chapter of history. As you travel through Jeju’s mid-mountain villages, you’ll see many towering hackberry trees. These areas are often remnants of villages burned to the ground during Jeju 4·3. Many were never rebuilt, left as ruins, or later converted into farmland. It’s not far-fetched to call them “lost villages.” These trees undoubtedly hold the memories of the atrocities committed back then.

Today, countless tourists visit Jeju for its beauty, but beyond that facade, lone hackberry trees in the fields quietly speak of the pain of that day. That’s the perspective from which I approached my pongnang project in 2020. Through this project, I published a photo book on hackberry trees in 2020.

One memorable moment was in 2022, when the bereaved families’ association held a ceremony to plant a hackberry tree in the yard of former President Moon Jae-in’s residence. On that occasion, they framed one of my pongnang works and presented it to President Moon.

Pongnang at destroyed neighborhood Sambatguseok in Donggwang Village (ⒸKang Jeong-hyo)

Pongnang at destroyed neighborhood Sambatguseok in Donggwang Village (ⒸKang Jeong-hyo)

Bonhyang Shrine for the guardian sprit of Waheul Village (ⒸKang Jeong-hyo)

Bonhyang Shrine for the guardian sprit of Waheul Village (ⒸKang Jeong-hyo)

What are your future plans?

I plan to continue documenting Jeju 4·3, organizing my materials, and expanding them to convey messages from diverse perspectives.

A few years ago, I conducted research on a lava cave in Jeju. It was less than 200 meters long, but as soon as I entered, I sensed something different. Stone walls lined the sides, and there were fragments of traditional water jars (heobeok). At first, I thought it might have been a shelter for refugees during Jeju 4·3. But as I ventured further inside, I found numerous cow bones. It struck me—could this have been a hideout for armed resistance groups rather than refugees? After all, refugees likely wouldn’t have had the resources to slaughter cattle in such a setting. These findings haven’t been disclosed or officially investigated. That’s why I’ve decided to gather and organize my records of visiting Jeju 4·3 sites.

Two years ago, I bought an infrared camera to pursue a new project. This type of camera visualizes infrared radiation (heat) emitted by objects to create images. When using this camera for normal shooting, the entire image appears red, as if everything has been painted red. But when processed with Photoshop, the green leaves are rendered white, making them look as if they are covered in snow. I thought that capturing Jeju 4·3 massacre sites in this way could convey several powerful messages. While some might see only red through tinted lenses, I wanted to reinterpret what the scenery of their hometowns might have looked like to those who faced death during that time. I am continuously experimenting with new ways to convey messages.

Are there any disappointing memories?

Many of my predecessors who organized photographs of Jeju used to say that during Jeju 4·3, there were only three or four photography studios in Jeju, and very few people could operate a camera back then. Even at the existing studios, soldiers would often bring their film to be developed, stand by until the photos were ready, and take all those of others away. Realistically, individuals couldn’t take photographs during Jeju 4·3, which is why there are almost no surviving photos from that period. However, this suggests that photographs may exist within military archives, making the discovery of such materials a task for the future.

When I was creating the photo book for the 70th anniversary of Jeju 4·3, I visited all the local newspaper offices in Jeju with official cooperation requests and met with the editors-in-chief. Most of the newspapers hadn’t properly organized their photo archives. But one paper did provide some photographs. That newspaper had considered discarding its old film reels when transitioning to digital. Fortunately, they preserved them and converted the content into a database. Many people, especially photographers, need to realize that photos are historical assets. Just because they don’t have immediate use doesn’t mean they’re irrelevant. That misconception is disappointing.

As someone who has documented Jeju, do you have any regrets about its changes?

I pursued a master’s and doctorate in tourism development. One might expect me to lean toward sociology or environmental studies. But my choice was driven by a desire to protect tourism from the negative impacts of tourism itself.

For Jeju to continue thriving as a tourist destination, we must clearly identify what needs protection and ensure development happens within those limits. In 1967, there was a plan to build a 1,000-pyeong (3,300m²) hotel within the Baengnokdam area, the summit crater lake of Mt. Hallasan, under the pretext of boosting mountain tourism to revitalize the local economy. But if a hotel had been built there, would Jeju have achieved the World Natural Heritage status we’re so proud of today? Even with development, we must prioritize sustainability. My idea is that we should protect what needs protecting without being reckless.

I feel that the value of Jeju is often underappreciated by its own residents. Looking at the process of Jeju becoming a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site and a UNESCO Global Geopark, international experts have highly praised the island, yet we seem unaware of its true worth. For instance, there are still fewer than five guidebooks about Mt. Hallasan, most of which I created. I did this because whether it’s Mt. Hallasan or stone walls, I felt that we didn’t truly understand our own heritage. There weren’t enough resources available, so I started working on it out of frustration. You have to first understand its value before expanding to how to protect it. That’s why I’ve been consistently working on projects related to our local community.

What would you like to say to the next generation leading the Jeju 4·3 movement?

When people talk about Jeju 4·3, they often mention reconciliation and coexistence. But I believe those are just steps in the process; our ultimate goals are peace and human rights.

I also want to emphasize that photography gains depth when it combines nature with the humanities. Don’t just focus on Jeju’s landscapes—also pay attention to the lives and stories of the people connected to them.

In the 1990s, it was possible to mentor younger generations because there were people eager to learn. Nowadays, everyone is so busy that it’s much harder. Back then, many artists didn’t have full-time jobs, but now, that’s no longer feasible—you’d starve. It’s not easy to sustain that kind of life today. Whether it’s Jeju 4·3 or Mt. Hallasan, these are topics that require long-term dedication. People often give up when they don’t see immediate results. But if you persist, it eventually becomes an invaluable asset to you. Chasing quick results makes it difficult. Younger people now need to develop their own interest. If an early-career photographer ever asks me, ‘How do I approach this?’ I’d gladly offer my help anytime.

Kang Jeong-hyo has authored several works on Jeju Island, pongnang (hackberry trees), Mt. Hallasan, and Jeju 4·3.