Unyielding Love and Endless Longing:

Consoling the Spirit of My Father, Who Was Left on the Street

Ko Dae-ok (Born 1939 in Sinheung-ri, Namwon-myeon)

Ko Dae-ok (born 1939) is the daughter of Ko Pyeong-sam (born 1904), who lost his life during the 1949 massacre in Namwon, a southeastern coastal village on Jeju Island. At the age of six, she was separated from her family and subsequently lived for a long time on Udo Island, a small island located off the eastern coast of Jeju. The little girl, left alone waiting for her father, lost all connection with her biological family due to Jeju 4‧3 and lived as ‘Yoon Bok-seon,’ the daughter of another household, for 85 years. After enduring decades of hardship, she reclaimed her own name and now seeks to restore her father’s name and honor him as a victim of Jeju 4‧3.

– Editor’s Note –

Interview, Documentation, and Photography

Ko Eun-kyeong, Research and Investigation Office

My Last Memory of My Father… An Endless Yearning

I was born in 1939 near Anjwa Oreum. There was my mother, my father, my eldest sister, me as the second child, and a younger brother. I can’t really remember if my brother died from sickness or hunger, since I was so little back then. We lived near Anjwa Oreum, first as a family of five, but it became just the four of us.

My father was short, and even though my memories are a bit hazy, I think the one thing I got from him is my height. I was small as a kid, but I was smart and capable. I later heard that by the time I was five, I was already helping take care of babies in the neighborhood. When I babysat, the families would give me pretty hanbok as a thank-you. Five years old―that’s such a little kid. A little kid taking care of a baby? Maybe that’s why they gave me those gifts.

I think I was around six years old when I heard there was someone—my grandaunt on my father’s side—living on Udo Island. When my father said we were going, I thought it was just going to be a fun little outing. The place my father carried me on his back to turned out to be Udo Island. Oh my, who would’ve thought that trip would end up with me living here all this time? When we got to Udo, I had no idea where anything was. I was so busy playing that I didn’t even realize when my father left the island.

I kept thinking, ‘He’ll come back if I wait. He’ll come back.’ But that was the last time I ever saw my father. That’s the only memory I have of him. What else could I remember as a child? The image of him, small in stature, carrying me on his back to Udo Island is etched in my mind. Maybe he cherished me too much to let me go, or maybe he felt guilty. Either way, from home to Udo Island, he never once set me down. He held me tightly on his back, carrying me as he walked onto the island. It must have been hard for him too. Now that I’ve raised children of my own, I understand. To carry me all the way to Udo without letting my feet touch the ground—what must have been going through his mind? How could he have turned and walked away, leaving me behind?

Born into the Ko Family, But Raised as Part of the Yoon Family

Our family was incredibly poor. I later learned that the grandaunt my father brought me to had agreed to raise me as her daughter. Back then, everyone was struggling just to get by. I can’t even put into words how much I suffered. I worked endlessly, doing whatever I could just to survive. As time passed, when I was about twelve, I got word from my sister that our father had died. She told me he had been shot. She explained that during the turmoil of Jeju 4‧3, he was killed by gunfire.

I was so young back then. When I heard he had passed away, I just thought, ‘So, I don’t have a father anymore.’ And that’s how I carried on with my life. The Yoon family must have felt sorry for me―an orphan living in someone else’s house. About a year or two after my father’s death, though I’m not exactly sure when, they added me to their family register. There was a boy in the Yoon family about my age, and they registered me as his younger sister. I was born in 1939, but on paper, I became ‘Yoon Bok-seon,’ born in 1940.

Being added to their family register didn’t change anything about my life. The only difference was that I was now ‘Yoon Bok-seon.’ I was supposedly their daughter, but in reality, I was nothing more than a servant. The house I lived in had a massive field—about 2,000 pyeong (approximately 6,600 square meters). I worked that enormous field by myself, often with a baby strapped to my back. Just think about it. Do you think I ever had a moment to straighten my back? I spent 20 years working in the fields and diving in the sea while living with the Yoon family. Did I even have time to feel sorrow? I was too busy just trying to survive. Then, at 22, I got married through an arranged marriage. It was a late marriage.

A Life of Poverty, Struggles as a Daughter-in-Law

I moved into my in-laws’ house with nothing. I couldn’t even bring a blanket when I got married. Who would give anything to a child they raised as a servant? I was expected to be grateful for being raised, housed, and fed. Even being added to their family register was something I was supposed to thank them for. So, I got married empty-handed. My in-laws didn’t have much either. At least when I was at the Yoon household, I didn’t have to worry about meals. But because I was an orphan who had been a servant in someone else’s house, they looked down on me. After marrying, I worked as a haenyeo (female diver) to help feed my in-laws. My mother-in-law kept the rice in a jar and placed it on top of the chest, carefully measuring its weight by each dwe (Korean measurement for 1350 grams) before cooking. Even leftovers were hidden back on top of the chest, so that I might not eat them. I felt so miserable. When my widowed sister-in-law came to visit, arguments would sometimes break out between my mother-in-law and me. If I ever reached my breaking point and spoke back to her, and my father-in-law happened to see it, all hell broke loose. From a hundred meters away, one of his shoes would come flying straight at my head.

“You cheeky wench, how dare you talk back to your mother-in-law? You’re nothing but an uneducated fool!”

My father-in-law made such a fuss while he was alive, even saying that he wouldn’t eat anything I made for ancestral rites or holidays after he was gone. It broke my heart to be looked down on just because I grew up without parents and didn’t get an education. On days when I had to hide behind a horse-drawn wagon for hours―or even days―to dodge his flying shoes, the only one who cared enough to come find me was my husband.

Parentless Myself, But a Good Parent to Seven Well-Raised Children

My late husband really cherished me. He always took me with him wherever he went, and when I had to go to the hospital, he held my hand tightly and stayed by my side. I didn’t have the blessing of good parents, but my husband treated me so well, and together we raised seven kids through sheer determination. One day, for our family of ten, we didn’t even have a single grain of rice for dinner. Even now, just thinking about that time makes it hard for me to even glance in the direction of Udo. As I was out diving with a neighbor from Gosan, I kept racking my brain, trying to figure out how I’d feed my family that evening. But no matter how much I thought about it, I couldn’t come up with a solution. Then, as we were walking, the lady from Gosan suggested we stop by her place for a moment. So, I followed her in. She took out some rice in front of me, carefully measured it grain by grain—one, two, three—and then plopped the pot onto the stove and said, “Let’s go.”

How naive I was. Worried sick about my family’s dinner, I thought the Gosan lady was going to give me some rice to feed us that evening. I really believed she had brought me to her house because she understood how desperate I was. Hoping for even a handful of rice, I stood there humbly with my hands clasped together, waiting while she washed the rice. I kept thinking, ‘When will she hand me some?’ But instead, she proudly cooked just enough for her own family’s dinner and said, “Let’s go.” I couldn’t bring myself to take a step. I didn’t even realize she was mocking me. She pulled at my clothes to get me to leave, as I stood staring longingly at the pot of rice. All I could think was, ‘If only I could take just one handful of rice, I could at least give my kids a few grains.’ The pain of that moment left such a deep scar in my heart.

Even now, just thinking about it makes my blood boil. I felt so miserable. After that, I completely stopped talking to her. I felt like she treated me like I didn’t exist, like I was a nobody—an orphan with no family, no support, no one on my side. And she did that right in front of someone who was struggling to figure out how to feed her family. Every time I think of Udo, all those bitter memories come rushing back. I don’t ever want to go there again.

Waiting for My Father, Not Knowing He Died Due to Jeju 4‧3

When I heard at twelve that my father had died, I… I was too busy just trying to survive, barely able to take care of myself. I couldn’t even properly attend his memorial rites. When my husband was still alive—my youngest daughter is almost fifty now—I think she was in middle school at the time. My husband and I went to my maternal family’s house for my father’s memorial rites. It was only then that it truly hit me—my father was really gone.

I attended the rites two or three times, but I stopped going because no one there welcomed me.

“Yoon Bok-seon, what are you doing here? You belong to the Yoon family now. You’re not a Ko anymore!”

When I brought my husband and youngest daughter to my father’s memorial rite at my maternal family’s house, my only sister spoke so coldly. Eventually, she even got angry and told me not to come. My mother couldn’t bring herself to say anything. She only said she was sorry for not being able to raise me herself. Though she didn’t express it much outwardly, it seemed like she felt pity for me. Later, she saved up small amounts of money, bit by bit, and put it under my name. She even left me a small amount of money before passing away in the nursing home, but my sister ended up taking it all.

“Dae-ok, take me with you, away from here. Please, let me leave this place with you…”

I can never forget the words my mother said to me when she was in the nursing home. At least she told me what happened when my father passed away. She said that my father had only planned to leave me on Udo temporarily because of our financial situation—not permanently. But not long after I was sent to Udo, Jeju 4‧3 broke out. Since I was on a different island, I didn’t know much about it, but chaos must have completely overtaken the village where my family lived. My father, mother, and sister were living in a village called Yeoune in Namwon, but I don’t even know if it exists anymore. In the winter of 1948, the entire village burned down, and my family had to flee to the mountains and live in hiding.

They managed to stay hidden for about three months, but eventually, my father was shot and killed. They mistook him for part of the armed resistance and executed him. My mother said she hastily made a stone grave for his body and left him there. That’s how I learned from my mother about my father’s death. I had been waiting for him, wondering, ‘Will he come today? Maybe tomorrow…’ Only to find out he died like that. Why did I even wait for my father by the sea on Udo as a child?

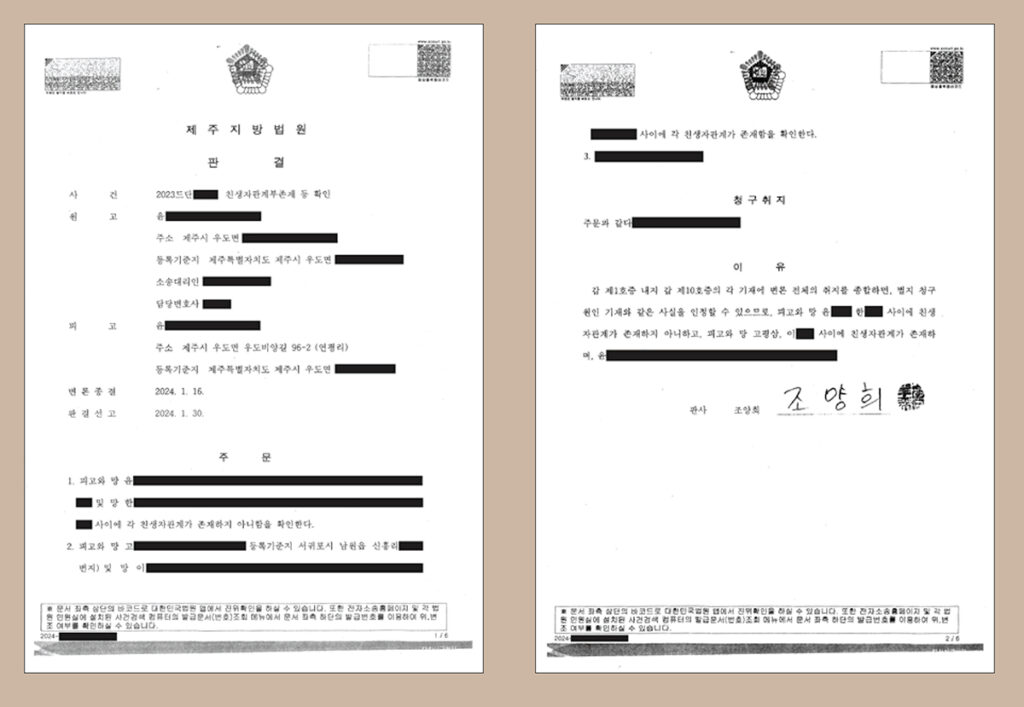

Court Ruling on Non-Existence of Biological Parent-Child Relationship between Ko Dae-ok and the Adoptive Father

If Only I Could Offer a Glass of Soju at My Father’s Grave

My daughter and I tried to find the stone grave where my father was buried. When we visited the village where my family used to live, there was nothing left, and it was hard to find anyone who remembered my family. It seemed like the grave had been moved, but we couldn’t figure out where. The place was completely overgrown with trees and grass, making it hard to tell what was where anymore.

“Father, it’s me. Dae-ok. I came to see you, and now I’m leaving. Rest well.”

With no other choice, I offered a drink to the air and said my goodbyes. Maybe sensing my sorrow, my youngest daughter told me last year that she would help me reclaim my name, so I could finally live as my father’s daughter. She worked so hard to make it happen, and I felt both sorry and grateful. I’ve lived my whole life as ‘Yoon Bok-seon,’ but now I want to live as my father’s daughter, ‘Ko Dae-ok.’ I want to bring peace to my father who died so unjustly. My father had no siblings, so no one remembers him as a victim of Jeju 4‧3. When I think of how he has no proper grave and is still wandering somewhere, it brings tears to my eyes. My mother didn’t know much, and my sister only thought of herself. They both passed away like that. My father wasn’t even properly reported to have died due to Jeju 4‧3. I only found out when my youngest daughter helped report him as a victim. How much anguish must my father have endured!

I don’t have much time left either. Will I get to meet him when I go to heaven? Before I go, my one wish is to find my father’s grave and offer him a glass of soju as a farewell. A life taken so unfairly, with no one left to remember him. I can’t help but wonder if he’s still wandering, unable to rest, because he hasn’t been laid to rest properly. I want to send my poor father off the right way before it’s my turn to go.