The Jeongbang Waterfalls Memorial Monument: Rescuing the Spirits of Jeju 4·3 Victims Hidden Beneath the Waters

Oh Soon-myeong

Chairman of the Jeongbang Jeju 4·3 Bereaved Families’ Association (born 1944 in Hahyo-dong, Seogwipo-si)

Interview and Compilation by Cho Jung-hee, General Affairs Manager

On April 11, 2015, during the Jeongbang Waterfalls Jeju 4·3 Haewon Sangsaeng Gut (a shamanic ritual for healing and reconciliation), a list of more than 250 victims massacred at Jeongbang Waterfalls was displayed like a fluttering screen. This was the moment when Jeongbang Waterfalls revealed its true identity as the largest massacre site in southern Jeju during Jeju 4·3. Among the hundreds of names listed, a man spotted his father’s name, ‘Oh Hee-yoon,’ and immediately broke down in tears. It was the first time in over 40 years that he revealed his identity as a bereaved family member of a Jeju 4·3 victim. His father’s death, which he had never dared to speak of due to the fear of guilt-by-association policies, overwhelmed him with belated regret and longing, and his tears wouldn’t stop. From that day onward, it took over eight years to establish a bereaved families’ association and erect a memorial monument. We spoke with Oh Soon-myeong, chairman of the Jeongbang Jeju 4·3 Bereaved Families’ Association.

– Editor’s Note

On April 11, 2015, Oh Soon-myeong, at the Jeju 4·3 Haewon Sangsaeng Gut at Jeongbang Waterfalls, bows before the site of his father’s death for the first time in 67 years. It was the first Jeju 4·3 event he attended at all.

The Jeongbang Waterfalls Jeju 4·3 Haewon Sangsaeng Gut in 2015

A few days before the 67th anniversary of Jeju 4·3 in 2015, a piece of mail was delivered to my home. The sender was marked as ‘Jeju Federation of Artistic and Cultural Organizations,’ and inside was a notice about hosting the Jeju 4·3 Haewon Sangsaeng Gut at Jeongbang Waterfalls. It was probably the first time I received a personal invitation to a Jeju 4·3 event. Such notices were typically distributed to schools or through official channels, and no one officially knew that I was a bereaved family member of a Jeju 4·3 victim.

My first thought upon receiving the mail was, ‘How did they know my address?’ Then, ‘How did they know my father died at Jeongbang Waterfalls?’ and, ‘How did they know I was a bereaved family member?’ Questions like, ‘What exactly is the Jeju 4·3 Haewon Sangsaeng Gut?’ and ‘What kind of organization is the Jeju Federation of Artistic and Cultural Organizations to host such an event?’ spiraled endlessly in my mind for days. I couldn’t ask anyone about it and kept all my thoughts to myself. ‘Should I go? No, I shouldn’t!‘ I couldn’t make up my mind. The idea of going just didn’t come easily to me.

Confronting my father’s death after 67 years

It was Saturday morning, April 11. The weather was exceptionally fine. The sky was deep blue, the sunlight was warm, and a gentle spring breeze was blowing. Maybe that’s what moved me to go. Even the night before, I kept wavering—should I go or not? Since I had already retired as a school principal, I didn’t have to worry about anyone’s judgment anymore. Still, it wasn’t easy to step forward as a bereaved family member of a Jeju 4·3 victim.

The place where my father died—a place I had never dared to visit before. I finally arrived at Jeongbang Waterfalls. I parked the car in the lot and walked toward the sound of people gathering. As I stepped into Sonammeori at Jeongbang Waterfalls, the sight before me was both shocking and deeply moving. What I remember most vividly is the sight of the cotton cloth with my father’s name, ‘Oh Hee-yoon,’ fluttering in the breeze. On the green grass of Sonammeori stood a carefully arranged shamanic ritual table adorned with colorful offerings. Above it, the names of those who perished at Jeongbang Waterfalls were written on strips of cotton, blowing in the wind. Among the hundreds of names, I spotted my father’s almost instantly. That was the moment it all began—when I finally confronted my father’s death again.

A photo of Oh Hee-yoon in his youth, father of Oh Soon-myeong

My mother and father reduced to a single grave

When I was nine, my grandmother took me to cut the weeds of my parents’ grave for the first time. About a kilometer from our house in Hahyo Village, there was a single, unmarked grave standing in isolation. I knew both my mother and father had passed away, so there should have been two graves, right? I asked why there was only one, and my grandmother snapped at me in anger. That’s when I realized, ‘Oh, I’m not supposed to talk about my parents!’ From that day forward, my mother and father became taboo subjects.

A year later, my grandmother took me again to trim the weeds. Then the year after that, and the next. Over the years, as we made these visits, I began to piece together why there was only one grave.

During Jeju 4·3, my father was taken to Seogwipo, and my mother went to visit him. Setting out from Hahyo Village and passing through Wolla Hill in Sinhyo Village, she encountered soldiers on a truck. Back then, soldiers would shoot indiscriminately—it was a mad world. My grandmother ended up retrieving my mother’s body from a draining ditch near Wolla Hill after she had been shot. Could my grandmother even hold a proper funeral? She managed only a temporary burial, and while desperately trying to confirm my father’s fate, she learned two weeks later that he, too, had been executed at Jeongbang Waterfalls. My grandmother, who lost her youngest son and daughter-in-law—both under thirty—had to bury them together in a single grave with her own hands. I can only imagine her anguish.

“It’s because of your father that innocent people died!”

After my parents died, I was sent to live with my maternal grandparents. Back then, they would round up and kill anyone, child or adult, labeled as a “rebels’ spawn.” What else could we do? It wasn’t just the soldiers and police we had to avoid. You couldn’t be seen by anyone in the village. I spent two months hiding in a sweet potato pit at my grandmother’s house. During the day, I’d crouch in that dark, cramped pit. At night, I’d crawl out and sleep curled up on the kitchen floor. I was only five. What did I know about death? I cried myself to sleep, terrified of the cold and hunger beyond words. After about two months, just as warmth began to seep into that cold, damp pit, I was finally able to return home.

“Hey, you rebel’s spawn! What are you doing here?”

It was clearly the house where I had lived with my parents, but strangers had taken over the main room and were acting like they owned the place. My grandmother hid in the small room, cowering like a criminal. That must have been when I started avoiding people. If I saw anyone while walking, I’d instinctively bow my head and step aside. Unlike other kids, I never got to run around and play freely in the village. I didn’t want to hear, “Don’t play with that rebel’s spawn!” Every time someone called me a “rebel’s spawn,” it felt like they were blaming me, saying, “It’s because of your father that innocent people died!”

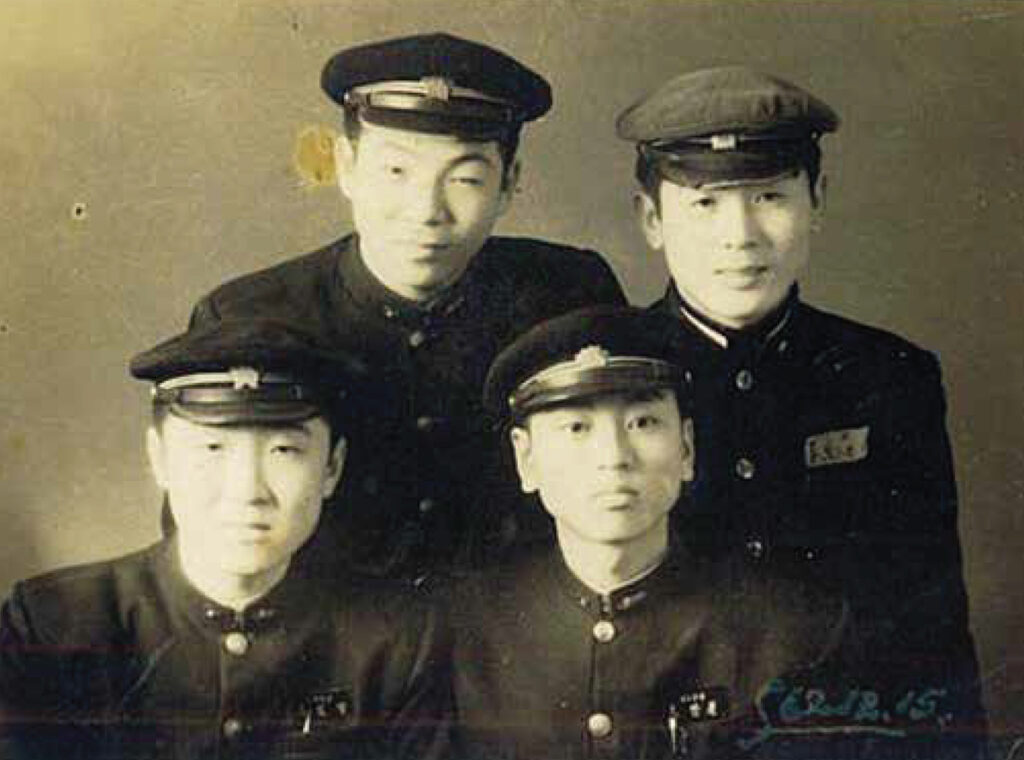

A 1940 commemorative photo of the 2nd Graduating Class from Hyodon Village School

(In the last row, second from the right, is Oh Soon-myeong’s father Oh Hee-yoon)

Ah, parents are supposed to be there!

I had always assumed I didn’t have parents. Living with my grandmother seemed natural to me. It wasn’t until I was in the third grade of elementary school that I realized it. In May, on Parents’ Day, my teacher wrote “Draw your mother and father” on the blackboard and told us to draw pictures of our parents. But I didn’t know what my parents looked like.

“Oh Soon-myeong, why aren’t you drawing? Come to the front!”

The teacher must have thought I was being lazy or rebellious, so they made me stand in front of the class and slapped my palms without explanation. At first, I felt embarrassed and humiliated, but then I became increasingly resentful. It wasn’t my fault that I didn’t know my parents’ faces! Eventually, my anger boiled over, and I couldn’t contain it. I didn’t go to school for a week after that. Now, I can only barely understand the teacher’s perspective. They probably thought, “Who in the world doesn’t have parents?” After that experience, I gradually came to realize, “Ah, parents are supposed to be there! I’m the only one without them!”

A turning point in life: Could my parents have watched over me?

It was when I had just started my second year of high school. One day, I saw a first-year student smoking. I couldn’t just let it go and scolded him like a typical upper-class senior. I guess I was meddling. That evening, around dusk, a couple came to my house. They were relatively young, and as soon as they saw me, they started hurling insults.

“You little punk! You bastard! Growing up without parents, are you planning to become a thug? A beggar?”

That day, I heard more insults than I ever had in my entire life. I couldn’t believe they’d come all the way to my house just to curse me out because I had scolded their son. But strangely enough, instead of feeling angry, I thought, ‘What will become of me if I don’t make an effort?‘ It was as if I had been scolded by my own parents, and it snapped me to my senses.

The next day, I picked up my discarded school bag, took out my books, and started paying attention in class again. Fortunately, I didn’t seem to lack the aptitude for it. Back then, I thought I’d get a job at a local government office after graduating high school. That’s how I spent the winter of my third year in high school. One snowy day, an envelope arrived at my house. Inside were an application form for a teacher’s college and a letter.

“Soon-myeong, what do you have to lose? Why not give it a try?”

My middle school friend, Won Geun-myeong, had bought the application form for me during his trip to Seoul for his college exams and sent it to me. Back then, teacher’s college was a two-year program with free tuition. I had never dreamed of going to college, but that application changed my life.

Third year in high school: Oh Soon-myeong (back row, right) with the friend who changed his life, Won Geun-myeong (back row, left). Nov. 15, 1962.

Graduating from Teacher’s College and facing the onset of guilt-by-association policies

After graduating from the teacher’s college, I waited for my teaching assignment like everyone else. All my friends received their appointments, but I heard nothing. As my anticipation turned into anxiety, I got a call from the police saying my background check hadn’t cleared.

“It’s because your parents died during Jeju 4·3! You’re affected by guilt-by-association policies, so it’s not possible!”

That was the first time I heard the term “guilt-by-association,” at the Hahyo Police Substation. I’d never encountered it before and had no awareness of it until then. It felt like my world was collapsing. I was utterly despondent. There was only one reason I went to teacher’s college: to become a teacher. I’d focused only on that goal without considering anything else. Now they were saying I wouldn’t get an assignment—what was I supposed to do? ‘Should I give up on life?’ I even had such extreme thoughts. Eventually, my relatives intervened. The Hahyo Police Substation called again.

“We’ll issue the background check, but under no circumstances should you mention that your parents died during Jeju 4·3!”

From that day on, I never spoke about my parents again.

Leaving Jeju didn’t mean escaping Jeju 4·3

At 22, I received my first teaching assignment at Nam Elementary School in Jeju City. Fortunately, teaching suited me well. At 24, I married earlier than most and immediately joined the military. I served in the 818th Artillery Battalion in Cheorwon, Gangwon Province. One day, a captain in the operations division noticed from the personnel records that I had been a teacher. He must have thought I could be useful. At that time, there weren’t many people who had graduated from university. “Private Oh! Would you like to work in the operations division?” “Yes, I’d love to!” But about a month later, they told me, “Private Oh, you’re not eligible after all!”

It must have been because of my background check. That’s when I realized for certain: even if I left Jeju, I couldn’t escape the consequences of my background. Not being able to work in the operations division was fine, but I worried about whether this might make my military life more difficult. I tried my best not to stand out—whether it was something good or bad. I became even more cautious to avoid drawing attention. To my relief, after 14 months, I was safely discharged for family hardship. Back then, being parentless was a valid reason for early discharge.

Oh Soon-myeong marries at the age of 24

40 years in teaching, turning away from Jeju 4·3

Throughout my nearly 40 years as a teacher, from starting as a regular teacher to retiring as a principal, I received countless official notices about Jeju 4·3 memorial ceremonies and other such events. Especially after the Jeju 4·3 Special Act was enacted in 2000, news about Jeju 4·3 frequently appeared on TV and in newspapers. Every time I came across such news, I always felt like attending. But I never did. Not even once. I could never know when my past experience with background checks during my first teaching appointment might come back to haunt me.

It must have been when they first began accepting applications for Jeju 4·3 victim registrations. One day, a second cousin of mine came to me with an application form. I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I told him there was no point in reopening old wounds I couldn’t heal anyway and didn’t want to stir up unnecessary trouble. But my cousin must have filed it on my behalf without telling me. A notification of Jeju 4·3 victim status arrived at my house. Honestly, I was terrified. It felt like my carefully hidden secret had been exposed to the world. I stormed over to my cousin’s house and tore up the notification in a fit of rage!

But no matter how much I pretended otherwise, I couldn’t lie to myself. Every April 3, I felt indescribably sad and depressed. In the evenings, after work, I’d watch the faces of bereaved families at Jeju 4·3 memorial ceremonies on TV, and tears would well up in my eyes. Every April 3, I’d drink heavily—something I normally didn’t do. My wife, my children, and my family must have been bewildered. Yet, I never talked to my wife or children about my parents or Jeju 4·3. That’s the life I lived—a life where I had to completely turn away from Jeju 4·3.

Commemorative photo of teacher training at Jeju Dong Elementary School. Oh Soon-myeong is the second from the right in the third row (Nov. 4, 1964).

May the Jeongbang Waterfalls Memorial Monument become a sacred site of Jeju 4·3!

Before the Jeongbang Waterfalls Jeju 4·3 Haewon Sangsaeng Gut, there was no clear recognition of the massacre at Jeongbang Waterfalls. Nobody could say for sure what happened at Jeongbang Waterfalls during Jeju 4·3, how many people were killed, who they were, or why they died. Even I only knew the date of my father’s death for ancestral rites. And even that, I kept secret out of fear others might find out.

At the Jeongbang Waterfalls Jeju 4·3 Haewon Sangsaeng Gut, I saw the names of my father and hundreds of other victims. That was the moment I decided we needed to build a memorial monument. I went through the victim list in the ritual booklet, verified each name, tracked down every family member to form a bereaved families’ association, and appealed to the local government authorities to erect the monument. Not a single part of this process was easy. But the hardest part of all was choosing the location.

Initially, we considered the Seobok Exhibition Hall, but since it was a cultural heritage site, no memorial monument or facilities could be built nearby. So, we moved to Sonammeori, but then nearby villagers began to oppose it. They called the Jeju 4·3 memorial monument an “eyesore” and put up banners saying “No to the Monument.” I was seething with rage. But we couldn’t just keep fighting the residents. Reluctantly, we moved to the Seobok Exhibition Hall parking lot, but the spot assigned by the authorities was next to the restroom. Naturally, the bereaved families opposed that, too. In the end, we chose what is now known as Bullocho Park as the final site for the monument. It took eight full years to finally hold the unveiling ceremony for the Jeongbang Waterfalls Memorial Monument on May 29, 2023.

We still need proper signage, an altar where people can place flowers, and, most importantly, to rename the park from Bullocho Park to Jeju 4·3 Park. That’s the top priority. I plan to turn this into a representative Jeju 4·3 park, highlighting its history as the largest massacre site in southern Jeju during Jeju 4·3. That way, we can properly educate the ignorant and inconsiderate people who call the Jeju 4·3 memorial monument an eyesore about the truth of Jeongbang Waterfalls and Jeju 4·3. Finally, I hope that the many Jeju 4·3 spirits resting in the cold waters can find their names on the memorial monument and rise to the warm land above.

Oh Soon-myeong delivers a speech at the unveiling ceremony for the Jeongbang Waterfalls Memorial Monument on May 29, 2023.