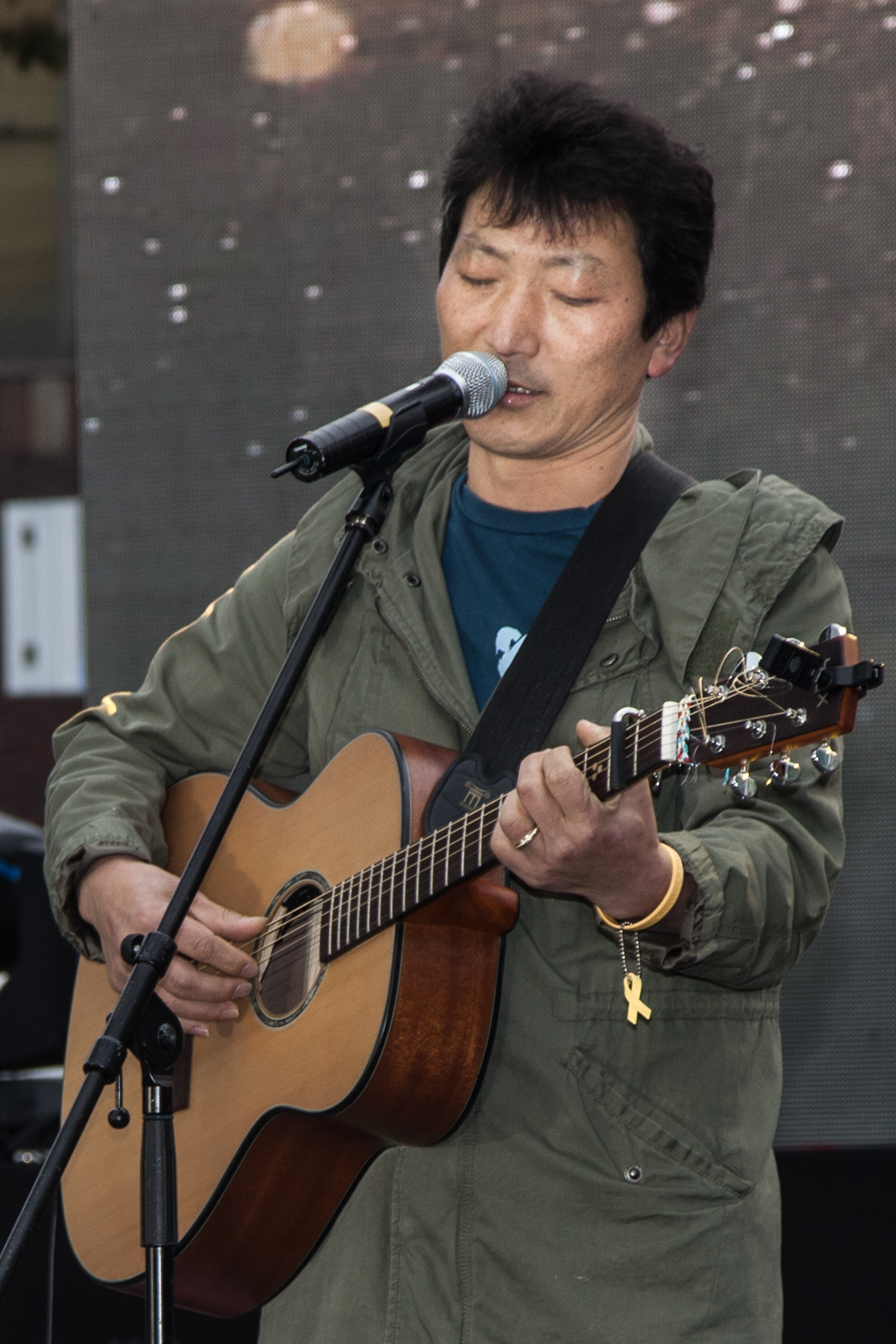

He sings for the resolution of Jeju 4·3

A grand stage was set at Gwanghwamun Plaza. A singer’s finger points to the U.S. Embassy, and the lyric says, ‘We cried under the shadows of the star-spangled banner – Oh, the time we spent being suffocated.’ It was a moment the audience could feel the retching from the inside. At the plaza, numerous actors, singers, poets, and the audience let fall camellia flowers while singing ‘The Song of Baby Camellia Blossoms.’ Performances such as ‘Yeoksamaji Geori Gut’ and ‘Halla, the Collective Drama’ were also performed. A collection of about one hundred flags that used to be hung across Mudeungiwat, the lost village in Donggwang-ri, was erected. A small stone pagoda was raised. Here, the songs the singer sang and the performances he directed were not only for the audience. They were a devotion to the spirits lost. It was a shamanistic ritual for the victims. The performers worked tirelessly, thanks to the singer’s devotion. I followed the trails of the arts of Jeju 4·3, and it led to the Jeju 4·3 Peace Park, where Choi, Sang-don, the singer, had his wedding ceremony.

Interview arranged and photos taken by Yang Dong-Gyu, a photographer and screenwriter

Choi, Sang-don, an artist, has directed several concerts and performances related to Jeju 4·3, such as the events of the eve of the commemoration of Jeju 4·3 and the cultural and art festivals for Jeju 4·3. He took part in the songwriting, lyrics, and story-telling in a ‘pilgrimage’ on the history of Jeju 4·3. His works in Japan include the Jeju 4·3 memorial services in Osaka, Tokyo, as well as performances held at the Jeju 4·3 Memorial Monument in front of the Tokoku-ji (temple) in Osaka. Until now, the artist has been a member of the Korean People’s Artist Federation Jeju Branch (JEPAF), a member of the steering committee of the Jeju Dark Tours, a chair of the music committee, a director, and an art director of the JEPAF.

<Most-renowned songs>

The Song of Baby Camellia Blossoms, Time, The Song of the Descendents of Jeju 4·3, Five Rules for the Nation’s Foundation, Remember 3·10 General Strike, Promise, Sangook, The Song of Yamada(山田), Halla-san, Yellow Cactus, The Lullabies of Moksimul Cave, You, Silver Grass and the Sunflower, Wind Blowing in the Prison, Jeongteureu Airfield, Fossils, Hyeoneuihapjang (graveyard), In the Village of Darangshi, Bukchon Gobeulak, Resentment of Seotal Oreum, Ieo-do Yeonyu, Birds of Korea Strait, Here We Live, and many more.

It has been a while since your last visit to Jeju. How have you been faring in Osaka?

It’s been about 10 months since I last came to Jeju, and I must say that I was not feeling well, especially with all the presidential and local elections. If I had been in Jeju, I would have met people and talked with them over a drink. In Osaka, I could not do so. I longed for Jeju and the people.

I would say it has been a relatively short span of time, but much has changed in Jeju, which makes me nervous.

The name Choi, Sang-don comes with the subtitles of the Jeju 4·3 singer and folk singer. You have sung songs of resistance and peace for the truth-finding of Jeju 4·3 and protests against the construction of the Jeju naval base. What caused you to become interested in such activities?

When I was young, I often saw my parents playing drums and janggu. When I got into college, I joined a folk music club. It turned out the club was an activist one. The nation was ruled under a military regime in the 1980s. It was a time when every university student had to face the political situation directly. In the club, I became interested in social issues as all the members discussed, argued, and sometimes fought over the issues.

By the time I was nearing my graduation, I heard news that human remains were excavated near Darangshi cave on Jeju. It was a shock to me. I made a pilgrimage to the site. That is when I first wrote a song about Jeju 4·3, feeling sad and noting the landscape. Upon graduation, I swore to myself never to lose the ties I had made regarding Jeju 4·3 in the club and in the social activities. I organized a singers’ activist group. I also requested consultations with the Jeju 4·3 Research Institute. This made me who I am now.

[Choi Sang-don and Yang Dong-gyu are talking about how Choi became interested in Jeju 4·3 while they visit the special exhibition on the Darangshi cave excavation at Jeju 4·3 Peace Park.]

You have been writing songs and lyrics yourself. When and how did you first write a song?

When I was in my third year of high school, there was a guitar that my older brother (does he mean his real older brother, or just friend? If it was his brother, it seems that it would just be ‘gave me.’) brought to my room. I wanted to play it and sing. I taught myself music, utilizing the knowledge I learned in primary school and middle school. I wrote my first song based on letters I exchanged with a girl I liked at the time. Its melody was later used to create the song, ‘Flame Fighter,’ which I presented while I was at Jeju National University. I met many people who played music from that time on and learned more.

It wouldn’t have been easy to make music using historical issues like Jeju 4·3. What has Jeju 4·3 meant for you in creating music?

Jeju 4·3 is something you cannot miss if you are from Jeju. You hear from your parents and older generations. The Jeju 4·3 story I was told by my mother, when I was a boy, (commas maybe not necessary) was about how the Imperial Japanese forces were ousted from Jeju. However, what I found out after I grew up differed. The stories I heard in college were about justice and the reunification of Korea, not about suffering and ordeals. They were slogans for peace. That inspired me to write songs about emptiness.

I was motivated to write music while visiting the ruins and sites of the mass killings of Jeju 4·3. Especially the atmosphere at the sites like the Darangshi cave overwhelmed me. I listened to the victims’ stories and the village’s lost history. It inspired my imagination, which led to creativity. Looking up Hallasan from a stream, I thought about the lives of the people during the incident. Those were important elements in the creation of my music. They become alive, unlike what you feel from reading a script about Jeju 4·3.

‘Singing April’ was your group. Then, you moved onto JEPAF, where you continued your ‘Jeju 4·3 music pilgrimage’ until now. We want to know more about it.

Even while I was in the group, there was at least one music concert in commemoration of Jeju 4·3 once a year. After that, I joined the JEPAF and came to a turning point in my career in 2001. I assumed the role of music director for the song, ‘The Song of Baby Camellia.’ It was then that I became more interested in plays and various music. That’s when I began studying about Jeju 4·3, visiting lost villages and oreums myself.

I listened to the stories of the survivors to write scripts and make music, and I loved the work. I felt that the spirits of the lost ones would be fond of it when I went back to the fields and sang my songs to them. At least, it allowed me to think I could contribute to healing those suffering. So, I gathered up a group of people a couple of times a month. When we first entered the fields, we held a ritual before the performance. The official version of this series of actions was the Jeju 4·3 music pilgrimage. Although it started out as a personal resolution, I had company every time I made my pilgrimage.

Was there a memorable moment during the pilgrimage?

There was a friend named Kim, Hyeon-mi with whom I traveled together. One time, we decided to walk from the 1,100-meter point all the way to Donggwang-ri. The path was to pay respect to the people who ran away from Donggwang-ri, as far as Doloreum and Bolleoreum. The idea was to bring those people back to their homes. The problem was we were lost in the middle and barely made it back. It was way more difficult than I thought. As we reflected, maybe it was a bit immature to bring the fugitives back home.

I can also still remember visiting prisons with the Association of the Bereaved Families members. It was in the middle of a hot summer day. Kim, Kyeong-hoon, a poet, kept saying that a hierophany of a spirit emerged from my sweat-soaked shirt. It seemed he saw a face of the spirits coming from my shirt.

On the daybreak of July 7, I walked from Moseulpo and climbed up Seotal oreum, from which one could see the streets, the towns and the landscape that victims might have seen. The red rising sun, along with the hot wind blowing from the still, dark land, came to me, totally different from what I had imagined in front of my desk.

I was also inspired by a rubber shoe worn by a baby in the cave of Moksimul, and came up with the song, ‘Lullubies of Moksimulgul.’

[Choi in the middle of the interview. The singer maintains seriousness as long as the talk is about Jeju 4·3.]

[Choi in the middle of the interview. The singer maintains seriousness as long as the talk is about Jeju 4·3.]

Personally, I can think of several songs such as ‘Time,’ ‘Ieo-do Song,’ and ‘Song of Baby Camellia,’ the most famous being the last one.

The ‘Song of Baby Camellia’ was not allowed to be sung at the commemoration event during the former regime of Park Geun-hye. The song became even more famous because of it. I first participated in the historical play as a music director in 2001 at JEPAF. It was a song I was asked to write upon a request by the general director, Kim, Soo-yeol. The play was supposed to be performed in April, and it was already February when I was asked to begin the work. At first, I was at a loss and wandered around many sites. I went to my childhood neighborhood. I imagined a boy waiting for his mother to return from fieldwork there. Also, the village was abundant with camellia trees. The symbolic flower of my former primary school was also the camellia, so I naturally focused on the camellia flowers while I was working on the song. Many people were separated during Jeju 4·3. They were waiting for their fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, sons, and daughters who ran away to the mountains. I couldn’t shake the feeling that all of those who ran away or waited died because of the incident.

That’s how the verse, ‘When it snows white in the mountains, the red flowers bloom in the field – the girl who went to meet her family burned and became the red flowers’ was made. I cried after writing the first one. I thought it was a great verse. I still think it was a good one. The verse is naturally good when you’re telling even an elementary school student about peace and the environment.