I cannot pick the brackens near ‘Gasinam Cave.’

Testimony of 4·3 by Chae, Gye-chu (born in 1927, Songdang, Gujwa)

In April 2022, A featured exhibition commemorating the discovery of Darangshi Cave was held in the 4·3 Memorial Hall. The names of 11 victims killed in Darangshi Cave were revealed, along with another list of 21 victims killed in the cave and the vicinity. However, there was also an explanation stating that the whole picture of the massacre in Darangshi Cave was yet to be fully revealed. All 21 victims were from Sangdo-ri and Hado-ri. Where were they killed? Was there a Darangshi Cave No.2 out there? What happened in the massacre of Darangshi Cave? One question led to another, over and over again. It was time for us to look for those who remembered what had happened at the time. We met Ms. Chae, Gye-chu in Gasinam-dong in Songdang, past Sangdo-ri and Hado-ri. She told us a sad story about ‘Gasinam Cave.’ She was about to give us the answers we were looking for.

Interviewed and arranged by

Cho Jung-hee, Team Leader of the Memorial Project Team

Photo by Kang, Bong-soo, photographer

Gasinam-dong, my hometown

While the residential registration says I was born in 1928, I was born in 1927. So, I am 96 years old. Initially, my family lived on Udo Island a long time ago. One of my ancestors was a county magistrate in the old town of Jeongeui. He made a nominal transfer and had my great- grandfather become the owner of Donggeomuni Oreum (a volcanic cone) in Songdang. He was also given some land lots for graveyards and farming as well. That is how my whole family became residents of Gasinam-dong, Songdang. There is nothing left now because of 4·3. However, there were about ten households in the area, including the Chaes, our home, the Kims, the Kangs, and the Sons. Now people call the area by the term Songdang. Still, there were smaller villages that had distinctive names such as Gasinam-dong, Neobeunbat, Alsongdang, Utsongdang, and Jangteodeuraengi. Less than 200 households were in Songdang, including those in Gasinam-dong, Neobeunbat, and Janeteodeuraengi.

“You want some buckwheat cake? (蕎麦の餅 たべますか?)

When Japanese troops manned the cave, which they dug inside Saemi Oreum, my second older brother was working in Songdang as a village secretary. His Japanese was good. So, we sold cakes made of sweet potato or buckwheat to the soldiers. I remember in Japanese, sobanomochi (蕎麦の餅) meant buckwheat cake, while imomochi (いも餅) meant sweet potato cake.

“You want some buckwheat cake? (蕎麦の餅食べますか)?”

“Yes, indeed! (はい! はい!)”

They paid in money or sometimes gave us a big, empty bottle that had contained alcohol. This bottle was called isupen (water bottle) and was very useful. You could fill it with cooking oil or lantern oil. The lantern oil was needed so that we could do sawing and cook meals. Ah, the soldiers also paid us with bamboo water bottles. Oh well; they’re all rotten and gone a long time ago.

The village of Gasinam-dong, where homes were lost during 4·3. The bamboo forest is all that is left to tell us that the place was once a home.

The Liberation of Korea, at the graveyard of my grandmother. “Hurray for the independence of Korea!”

I was eighteen years old when my grandmother passed away. It was July by the lunar calendar. War was going on, and I was scared whenever I heard the airplanes’ roars. “They’re going to bomb us!” I often shouted and hid under the trees and beside the stone walls. I had not seen any airplane myself, but I was scared to death anyway. My grandmother was buried not far from home. She was buried in the field she used to farm. Then one day, I heard rumors.

“The Japanese surrendered!”

Many people came to the funeral, including guests and relatives. And suddenly, we began shouting, “Hurray! Hurray!” Everyone who was there was shouting, “Hurray for independence!” We were so happy! When the Japs were around, we had to give them everything as offerings, from brackens to barley. Everything we collected and produced. We had to give them everything, so I could not even wear rubber shoes! I had to wear straw shoes and bleed while working for the offerings. That’s why we were so happy at the news that ‘the Japs surrendered.’

Ms. Chae pointing at the ruins of her old home in Gasinam-dong

The beginning of Jeju 4·3

“Never write the name on the list!”

I was 20 when I got married and moved to Alsongdang. That’s when it began. Every night a bunch of people shouting “Watsha! Watsha!” demanded my mother-in-law turn over her son, my husband.

“Never write the name on the list!”

My second older brother told the mob not to harm us, but my husband and I were so afraid at night that we could not get decent sleep. In the old days, we used to dig a hole and bury the sweet potatoes we collected. We would eat them during the winter and spring when there was little food. Anyway, my husband and I sometimes hid in that hole. But these men poked us with steel rods. Later, we escaped to my husband’s uncle’s field and returned in the morning. I barely lived because my name was not on the list. Those who were are all dead now!

“Why spend money when we’re not the rioters!?”

There was news telling who burnt down what or who was killed. It wasn’t very comforting! The counterinsurgency forces told us to leave all the cows and horses and move to the coast because they would burn down all the villages in the mid-mountainous areas. My parents had moved to Pyeongdae, my mother’s home, before marriage. I had not seen my parents for some time, so I decided to join them since I was pregnant. Because my husband’s home was full of people and we had to live inside someone else’s home, I did not want to go there.

Immediately after I moved to Pyeongdae, my father and his older brother were taken to the Sehwa police substation. It seemed that when my uncle moved down to the coast, their family cooked and ate a pig they used to raise. They were going to leave the pig anyway. He gave a leg of the pig to his second wife, who was eventually caught on her way back to her parents in Hado-ri. She was captured near Darangshi Oreum by the counterinsurgency forces.

“You are rioters! You provided food to the rioters!”

She explained that the food was a home-cooked meal, but to avail. So my innocent father and uncle were taken away. They were in their 60s. They had nothing to tell, even when they were being tortured. The counterinsurgency forces seemed tired and released them. Instead, they took away my second older brother. He had been the village secretary since the Japanese colonization because he was brilliant. He was famous as ‘Songdang’s bond manager, Chae, Gap-jin.’ He was so popular that even the rioters tried to lure him to their side. However, my brother was never a person to be swept away, nor did he have his name on any list. He told his siblings and cousins, “How can you win when you’re hiding in the mountains? You have to follow the law!” He also attended the meetings of the counterinsurgency forces. That’s why my brother’s capture meant a conspiracy was going on.

“Why spend money when we’re not rioters!”

There was a conspirator who had attached himself to the police officer at the substation. We all knew him. We all knew he tried embezzlement. It was my brother who stopped him. The substation caught and tortured my brother. After martial law, my brother was killed. I feel so sorry about my brother.

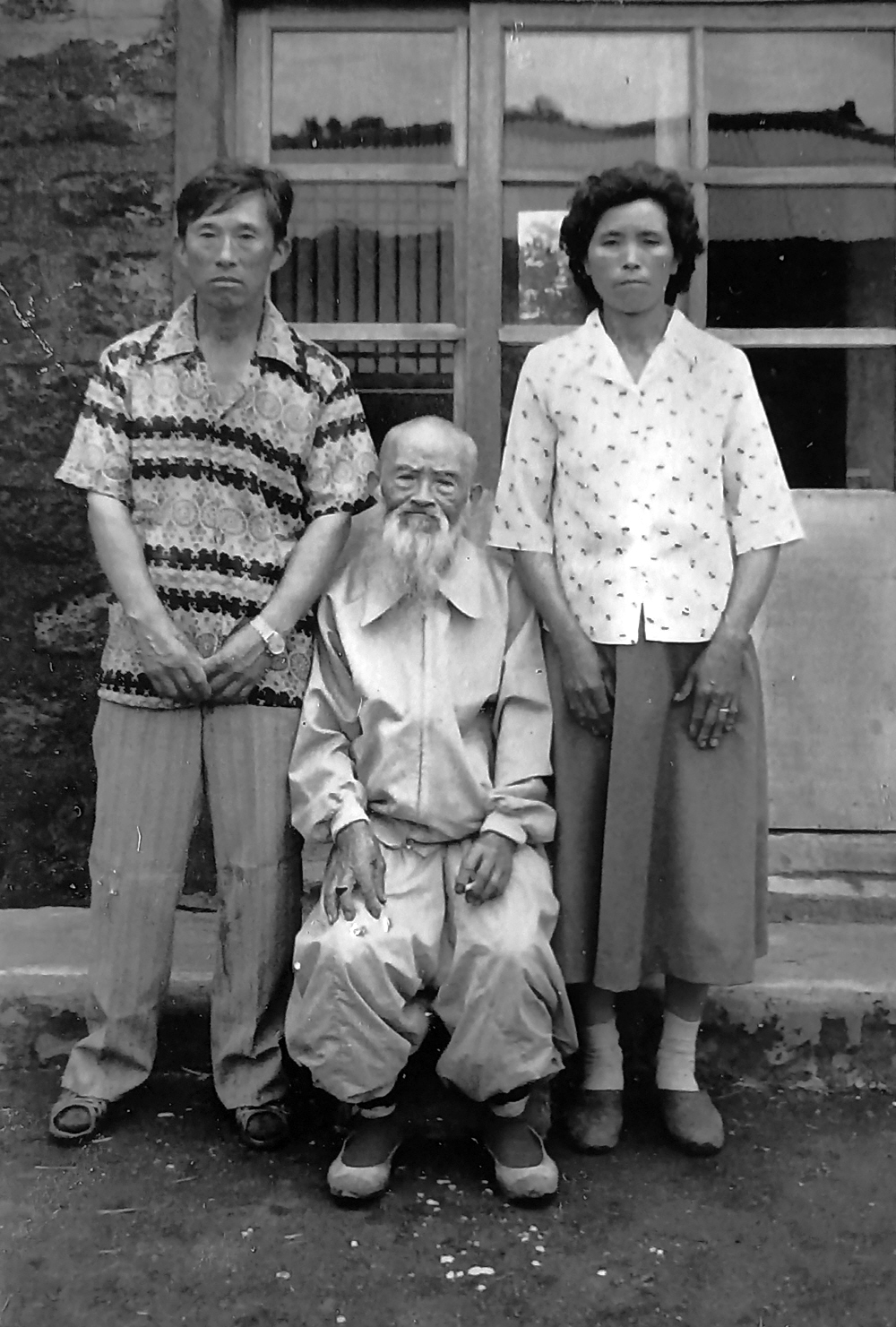

Ms. Chae in her younger days with her father-in-law and her husband

My second older brother was buried wearing my father’s shroud.

Oh! They could have killed him in different ways, like shooting him! Anything else than being speared to death! He was killed on the beach sand of Woljeong-ri by the steel spears that were meant to protect the people! Those who speared my brother were the rangers supposed to protect us! My second older brother died on January 4, 1949, by the lunar calendar (February 1, 1949).

After the turmoil became quiet, we could move back to Songdang. My father, not even close to having recovered from the wounds inflicted during his torture, ran to the sand beach of Woljeong-ri to find his son’s corpse. Fortunately, my father was able to recognize the face. However, the flesh was torn. There were dead maggots in the bones and intestines. He would have been better off if he had been shot to death. To think that the maggots fed off my dead brother… Oh! I feel so bad about my brother, and there is nothing left I can do about it but cry.

Would it have been better if he had joined the riots and been caught and killed? My father had my dead brother wear the shroud that had been made for himself at the funeral. He even took that shroud when we left our home to the coast. He was so proud of his second son, who took the place of his eldest brother, who died earlier. Before we could relocate my brother’s tomb, my father died at 62.

Damselfish soup I barely managed to cook after the birth of my first child.

In the meantime, I gave birth to my first child. I was pregnant when I moved to Pyeongdae. When I came back to Songdang, it was time for the delivery. It was the day when I left home for Sehwa to get flour. Suddenly, my stomach ached. I discharged blood, and I knew nothing about giving birth. I thought I would die on the road, but a horse carriage passed. Luckily the owner was a neighbor of my mother-in-law and knew her well.

“I won’t blame you for anything. I want to die at home. Just take me home, please.”

As soon as I was picked up by the horse carriage and delivered to a hut in Songdang, I gave birth to my child. It was June 5 by the lunar calendar. The rain was heavy. We weren’t at home. I was exhausted, and so was my baby. It was known that buckwheat flour was good for thinning the blood. But was there anything like that around? No. I only had boiled buckwheat flour one time. The rest of the time I was served with sujebi (hand-pulled dough) made out of wheat flour that was given as distributed food. My wound could not heal fast. Back then, it was also known that one is recommended to eat fish soup for recovery three days after giving birth. The fish should be a proper one with scales, not ones like mackerel or cutlassfish. Oh, well! Where would you find that kind of fish, huh?

Almost 20 days after the birth, one of my cousins, the daughter of my father’s younger brother, came from Hamdeok to Songdang to sell damselfish. After all, damselfish is a kind of fish with scales. So, I bought it and made soup out of it. I cannot forget the taste of it even now. It was the first soup I had had in 20 days after the birth of my first baby.

Ms. Chae is pointing to the location of Gasinam Cave. On the far left is Darangshi Oreum. The smaller hill on the right is Eomseolmaru. Gasinam Cave is located south of the hill.

The burial of my first baby without my husband

My first baby died after all the toils of delivery. That was when I was living alone in a hut. I was alone because the military had conscripted my husband. I had no medicine. There were no pharmacies or hospitals in Songdang. I only took my baby to an old Korean medicinal doctor named Ko in Geomheul. He was famous for acupuncture. Since I had little to eat, it must have affected the baby as well. I could not feed my baby well. Did I have some rice to make porridge for my baby when my breastmilk was poor? I could not do that either, and I am so sorry for my baby. I could not even feed him sesame porridge. I was 22 when I buried my first child in vain. When my husband came back home on leave, I was 27. We had our second baby. My parents-in-law wanted children so badly. Maybe it was because my husband was an only child. I gave birth to children one after another every two or three years. In the end, there were seven children. We weren’t rich, and I had to raise them all. How easy could that have been? We were always short on clothes and food… We barely made it.

Are you familiar with ‘Gasinam Cave?’

There is a small hill called Eomseolmaru in Gasinam-dong where I used to live. It was a bare hill without trees I used to play on that hill, picking brackens since I was young. In front of Eomseolmaru was a Ke, a flat field where horses and cattle are often released for grazing. The people of Sangdo-ri used to send their herds to the Ke. During the day, the herd grazed on the ranch of Donggeomun Oreum. At night, they were locked up on the Ke near Eomseolmaru. The following day the herd was again sent to Donggeomun Oreum because there was nothing to graze on in the Ke. On each day the people from Hado-ri and Sangdo-ri took turns to stand watch over the herd. There were three ponds, called Saetongmul, on the Ke. So, that was the place was best for keeping the herd. South of Eomseolmaru is a cave. The entrance is flat and stony, so one must bend on one’s knees to get into it. The ceiling is still low even when you get farther in. It is too low for an adult to stand up. But it was wide enough to be used as a large room. When I was young, I wandered into the cave after picking brackens near Eomseolmaru. There were bats on the ceiling flapping their wings, so I was surprised.

A house she built in Alsongdang after the evacuation from Pyeongdae during Jeju 4·3. She has lived her whole life here, raising seven children.

Escape to Gasinam Cave, subjugation, and massacre

When the incident began, the people from Sangdo-ri and Hado-ri came up to the cave at Gasinam and hid. The people and their families who had sent their herds were there. Every time they stood watch, they would come to my home and stay for a night or two, so we knew them well. There was a cave to take shelter in and water to drink near Eomseolmaru. The fugitives would dig up the crops and sweet potatoes that the people of Gasinam-dong stored. They used the millstone of Gasinam-dong to grind the crops and cooked meals with it. However, the counterinsurgency forces wandered among the mid-mountainous villages and stirred the place up, looking for rioters hiding in the cave. They made the young people from the villages lead them. A unit called the rangers followed the young people, and my husband (Jeong, Sang-il) was one of the rangers. My husband was ordered to join the hunt. When they reached Eomseolmaru, there was smoke. When they followed the smoke, they saw people sitting inside the cave. The counterinsurgency forces dragged all the people inside the cave. There were men and women, and one of them was pregnant.

I heard they lined them up in a row and shot them all, saying that those people weren’t worth shooting bullets one by one. My husband felt sick seeing those people being shot and helplessly tumbling down. He felt terrible about people being killed and was frightened. After the killing, my husband made bizarre noises whenever he drank, like “ah, ah, ah.” He frequently woke up at night, frightened and panicked, so I had to ask for a shamanistic ritual to cure him.

How much I liked the brackens… But I cannot pick the brackens near Gasinam Cave.

Rumors spread about the mass killing at Gasinam Cave. The young people who followed the rangers saw it. For some time, the bodies were left there. It was not because we did not know who they were. It was because they were killed in the name of the riots. Nobody dared to recover the bodies, risking being framed as rioters. After a while, when things quieted down, I heard that their families secretly recovered the bodies. The area around Eomseolmaru and Gasinam Cave has been ripe with brackens. The place was famous among all the people in Songdang. So, what? I am scared to even set foot inside after what happened there. I don’t even care about the place being my old home. I don’t want to go there. I like brackens so much. But to think of the people killed there, how am I supposed to pick brackens from there?

I regret my whole life not having served my father a meal.

I am my father’s daughter, yet I have not been able to serve him a proper meal. It is what I regret the most my whole life. Luckily, my mother did not pass away until she was 77. I was able to do some good for her. I served her meals, and my grandchildren were there to please her. But my father couldn’t see it. He died right after I married, and after Jeju 4·3 broke out. I have regretted this my whole life when thinking about my father’s untimely and miserable death. A few years ago, I performed an ancestral ritual for my father myself. I prepared all the food I could to make up for all the food I could have served him until then. Two years ago, when we relocated the tombs of my mother and father, my feelings were somewhat resolved. I made silk pants, a handkerchief, and a dharani (a Buddhist incantation). I couldn’t serve my parents a good meal before. Now that I have woven clothing for them to send them away, I feel a little more relaxed and relieved. This is the best I could do, and I am pleased about it.