Death was that simple

The sound of a sewing machine raised the son taller.

The needle that pricks skin-like fabric over and over

sews and stitches the ripped and torn life back together.

After father passed away during the 4.3 massacre,

mother tailored and mended for others

to educate the little ones, to rebuild the utterly indebted home.

And so her son’s faithful devotion grew, and her words became law.

Hand-carved phoenix desk

Kang Jung-hoon used his father’s desk to read books and to write. The desk, with an elaborate carving of a phoenix on each of its sides, serves as a repository of records and a sanctuary of memories.

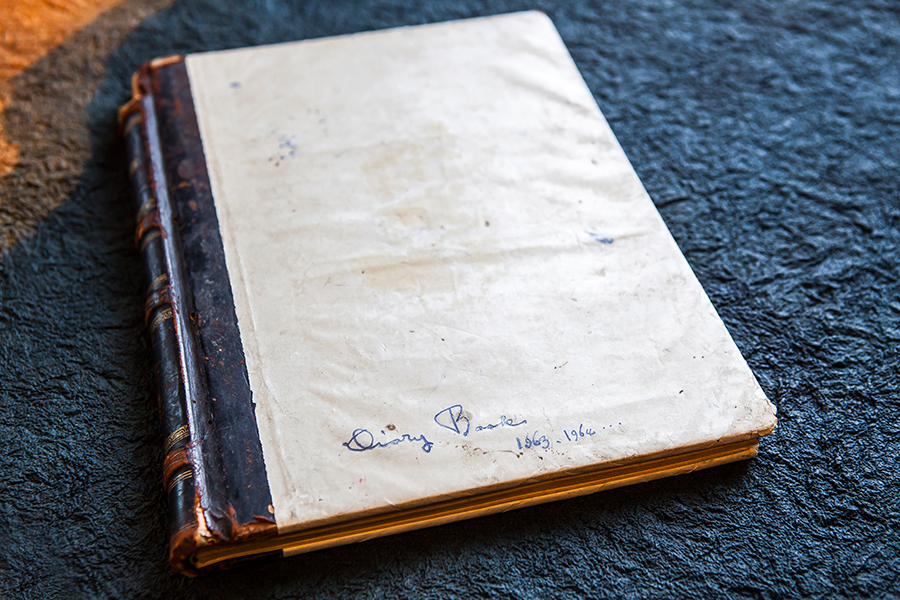

Ledger book

Kang’s father kept this ledger book from when he did business in Japan. Kang removed pages with writing on them lest they cause harm to the owners of the names recorded within.

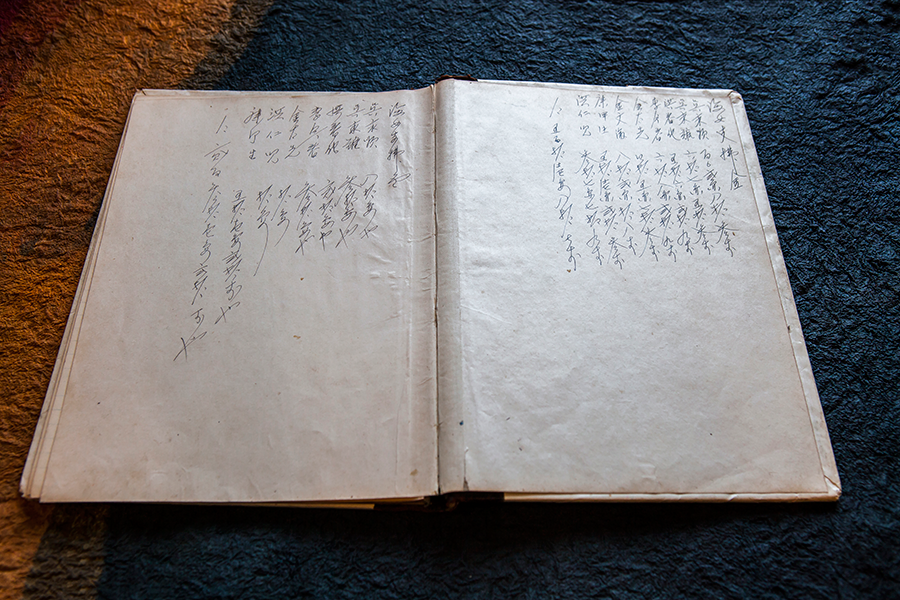

Father’s handwriting

The front cover of the ledger book is the only page with writing by Kang’s father. On the remaining pages, Kang practiced writing poetry. After spending some years wandering throughout the country, Kang finally became a poet. In his poems, he sings about the continuing painful history of Jeju 4.3.

“The victims were killed as if they were a shoal of anchovy — they all died together. This place is called Teojinmok. Over 490 people were massacred here over two years, starting from November 1948. I was eight when I witnessed my grandparents, my father and his two brothers and sister murdered. Death was that simple.

On a spring day the previous year, my father and I returned home from school after my school entrance ceremony. We were sitting on our wooden porch, talking. Suddenly, his face turned serious and he said, ‘Tell them I’m not here. Tell them I don’t live here.’ And he hurried to the shed. As soon as he hid there, police forces raided my house. Stepping on the floor with their military boots on, they searched for my father. I was terrified and even wet my pants. But at such a young age, I thought I had to protect my father. So I asked them why they came. I told them that he was not home, and that he had been away from home for a long time. I was so calm and confident. The police officers opened the drawers of this desk and said, ‘It’s not here.’ Then they searched through the gwe, and again they said, ‘I can’t find it.’ And they left my house. But they kept chasing after my father. That is why I can’t forget this desk. This brings back the vivid memory of that situation.

After my father passed away, my mother sewed to raise us. We lived by this (sewing machine). When I became a teenager, I hated Jeju and ran away to Seoul. But I came back and had my house built right in front of the site of the massacre. It is now a memory I can’t avoid. Facing it, however, soothes me.