The 90th anniversary of Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement, and Jeju 4·3

Special Discussion

The 90th anniversary of Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement, and Jeju 4·3

Park Chan-shik

President, Jeju Culture Promotion Foundation

Memories of Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement brought back during Jeju 4·3

Late in June 1948, Kim Sang-hwa, a reporter for the Gwangju-based Honam Shinmun, published a series of seven articles under the title of “A visit to Jeju, an island of turbulence” covering Jeju while the island was in the vortex of Jeju 4·3. To introduce the outbreak of the chaotic incident, Kim retold the history of resistance of the Jeju residents as follows:

Needless to say, the Uprising of Lee Jae-su [the 1901 Jeju Uprising], which left a pioneering lesson of a revolution, occurred at the end of the Joseon Dynasty in scathing defiance of the government-inflicted oppression of Jeju residents. In another historic event that happened hundreds of years earlier, the enraged residents of Jeju Island, led by Bang Seong-chil, stood up against the immoderate oppression inflicted upon them by the governor, eventually correcting the administrative affairs. Other events under Japanese colonial rule, such as the struggle of residents during the nationwide March 1 Independence Movement, the well-known uprising of Jeju haenyeo, and many other movements led by students, also broadly spread patriotism and progressive ideas among innumerable young people.

With regard to the historical background of Jeju 4·3, the eyes of journalists from outside Jeju Island were on the 1898 Peasant Uprising (led by Bang Seong-chil), the 1901 Jeju Uprising, the 1932 Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement, and the like. These events brought up historical memories behind the uprising and the resistance movement of Jeju 4·3.

As this year marks the 90th anniversary of the full-scale Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement, the related historical memories have been revisited. In January 1932, more than 1,000 haenyeo in the eastern region of Jeju Island, including the Hado, Jongdal, Sehwa, Udo, Siheung, and Ojo villages, took to the forefront of the anti-Japanese movement. Due to the region’s extremely infertile land conditions, it was difficult for any woman in the area to survive without doing muljil (diving underwater to harvest seafood). It wasn’t until they began attending night schools that they became newly aware of the value of their muljil work, which had been deemed simply as a means to make a living. By taking night classes, haenyeo received modern, nationalistic education from young intellectuals who lived in their neighborhoods. They studied books written for the purpose of expanding one’s horizon, such as “Nongmin Dokbon” (“A Reader for Peasants”) and “Nodong Dokbon” (“A Reader for Workers”), while being taught how to read the Korean alphabet and Chinese characters, and even on how to read scales.

Entering the 1930s, the Jeju Haenyeo Association, which was supposed to guarantee the rights and interests of the haenyeo, became thoroughly controlled by the government, with its tyranny running to an extreme. Under these circumstances, Kim Ok-nyeon and other haenyeo organized a new association to solidly stand up to the government-backed Jeju Haenyeo Association. Eventually, their struggle against the Jeju Haenyeo Association, which began in December 1931, unfolded as a large-scale protest through gaining momentum during the Five-day Market days on Jan. 7 and 12 of the following year.

During the Jan. 12 protest, women divers holding jonggae homi (hoes used to collect seaweed) and bitchang (sickles used to collect abalone) rushed Jeju Gov. Taguchi Teiki and his party as they were passing through Sehwa Village, shouting, “If you respond to our demands with a sword, we will respond with death!” The Japanese police suppressed the protest by force. Heanyeo leaders, including Kim Ok-nyeon, Bu Chun-hwa, and Bu Deok-nyang, were arrested, but their anti-Japanese spirit did not break under six months of torture and interrogation by the police. The haenyeo’s struggle is considered in Korean history as a women-led public movement against Japan that did not occur in other parts of Korea during the Japanese colonial period.

[The busts of Kim Ok-nyeon, Bu Chun-hwa, and Bu Deok-nyang, the three leaders of the Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement, were erected in Yeondumang Hill in September 2018.]

Historical memories of the Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement leaders

The historical memories of the 1931-1932 Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement haves been clearly imprinted in the minds of Jeju residents for more than 90 years. In the decades following liberation, those who led the nation’s public struggle from the March 1 Shooting Incident through the Jeju April 3 Uprising accepted the haenyeo’s fight as an example of the resistance of Jeju residents. Under the military regime after the 1960s, however, Jeju-based historians evaluated the haenyeo struggle as a simple movement to protect their rights, rather than as an anti-Japanese movement for national liberation, because the victim mentality of the public and anti-communist ideology remained predominant.

With the heightening atmosphere of the democratic movement in the late 1980s, a new evaluation of the popular movement under Japanese colonial rule was made, along with the production of subsequent empirical studies. Moreover, the national level of independence merit bestowed on the key players helped the haenyeo struggle become recognized by the state as an official history related to the nation’s anti-Japanese independence movement. Those leaders, such as Bu, Kim, and Ko, lived with a clear memory of their struggle as an anti-Japanese movement. They were women who led the struggle in January 1932 in which more than 1,000 haenyeo members from the Hado, Jongdal, Sehwa, Udo, Siheung, and Ojo villages participated. On behalf of all participants in the haenyeo struggle, they negotiated with the Japanese-born Jeju governor. Bu and Kim were arrested by the police and suffered hardships for six months while confined in detention at the Jeju Police Station as prisoners on trial.

Bu became a haenyeo at the age of 15. It was in 1923 when she began to realize modern national consciousness after studying Hangeul during night classes offered by the Hado Village Common School in Gujwa. In 1928, the then-21-year-old haenyeo was appointed as the representative of the Gujwa Regional Haenyeo Association under the umbrella of the Jeju Haenyeo Association and served as chairman of the regional branch. Later, Bu remembered the haenyeo struggle and accurately recognized it as an anti-Japanese struggle. Compared to what she remembered, her ties with the Hyeogwoo Alliance and her guiding local youth remained uncovered. Social activists have simply been remembered as the masterminds behind the struggle. For Bu, the red complex of Jeju 4·3 overlaps with her memory of the haenyeo struggle. She said in a testimony, “I returned to my hometown after national liberation and experienced Jeju 4·3. When the counterinsurgency forces left, I suffered another ordeal. At the time, each village had people write a letter of repentance, which I persistently refused. I said I would write a letter of repentance if they told me what I had done wrong. Then, out of nowhere, they mentioned the haenyeo struggle. I scolded them. The haenyeo struggle happened in early spring when I was 24 years old. Now it’s been more than 50 years since then. That incident chased me all my life.” This testimony shows that social memories of the haenyeo struggle and personal memories collide while experiencing the turmoil of Jeju 4·3.

Kim Ok-nyeon started performing muljil when she was nine years old. Being a good diver, Kim ranked first or second among the divers of her age. Despite the opposition of her parents, she went to night school and became educated. Later, she remembered that attending night school had been an important turning point in her life. She recalled, “I encountered a really good opportunity, which made a big turning point in my life. I mean when a night study center opened in my village, I used my evening hours to flee my parents’ opposition and study in the center. This lasted for two years. By attending night school, I met my husband and formed a relationship with those who led the haenyeo struggle with me. During the Japanese colonial period, the night school provided education mainly for conscious young male intellectuals as part of the independence movement; and on the other hand, it created opportunities for women to study as well. As independence movements were easily detected and suppressed at the time, the teachers worked to enlighten the public nationwide as an indirect and long-term preparation for independence.” According to her testimony, the haenyeo movement was “an organized anti-Japanese struggle led by Bu Chun-hwa and myself, who had been taught by Oh Moon-kyu and Kim Soon-jong, core members of the Jeju Island Youth Council”.

She was arrested by the Japanese imperial police for playing a main role in the haenyeo struggle, for which she spent six months in jail. While being interrogated, she was beaten with a cow whip, she had her arms twisted behind her back, and was forced to kneel on a wooden bar several times. During her testimony, she also remembered night school teachers who had taught her Hangeul and the history of the Korean people, while escaping the vigilance of the Japanese government, as well as young people affiliated with the socialist movement who had been imprisoned along with her for their involvement in the haenyeo struggle. Later, she married Han Young-taek, a young man from Jongdal Village who protested along with her in the haenyeo struggle. After national liberation, however, she would never see her husband again as he made the voyage to Japan and then to North Korea during the repatriation of Korean residents. The pain the leading actors of the haenyeo struggle suffered due to their participation in the anti-Japanese movement was compounded by the events following national liberation, such as Jeju 4·3 and national division.

The South Korean government has taken the process of recognizing the series of academic and local government achievements to remember the haenyeo struggle as an anti-Japanese movement. On Aug. 15, 2003, the government officially declared the struggle as an anti-Japanese independence movement by awarding two haenyeo members (Bu Chun-hwa and Kim Ok-nyeon) and two members of the Hyeogwoo Alliance (Moon Do-bae and Han Won-taek) the independence merit for their efforts. Subsequently, the selection of additional winners of the merit were announced on March 1, 2005, including to Kang Chang-bo, who had taken responsibility for the Jeju branch of the socialist group of Yacheika, and Kang Kwan-soon, Kim Seong-oh, and Kim Soon-jong, who had been members of the Hyeogwoo Alliance. On Aug. 15, 2005, the independence merit was also presented to Bu Deok-nyang (the other member of the three main actors of the haenyeo struggle), Shin Jae-hong (the virtual leader of the Hyeogwoo Alliance), and Chae Jae-oh (a member of the Hyeogwoo Alliance). With this, the haenyeo struggle gained the status of a nationally recognized anti-Japanese independence movement and regained its place following repressed under the anti-communist regimes in the history of Korea’s democracy movement.

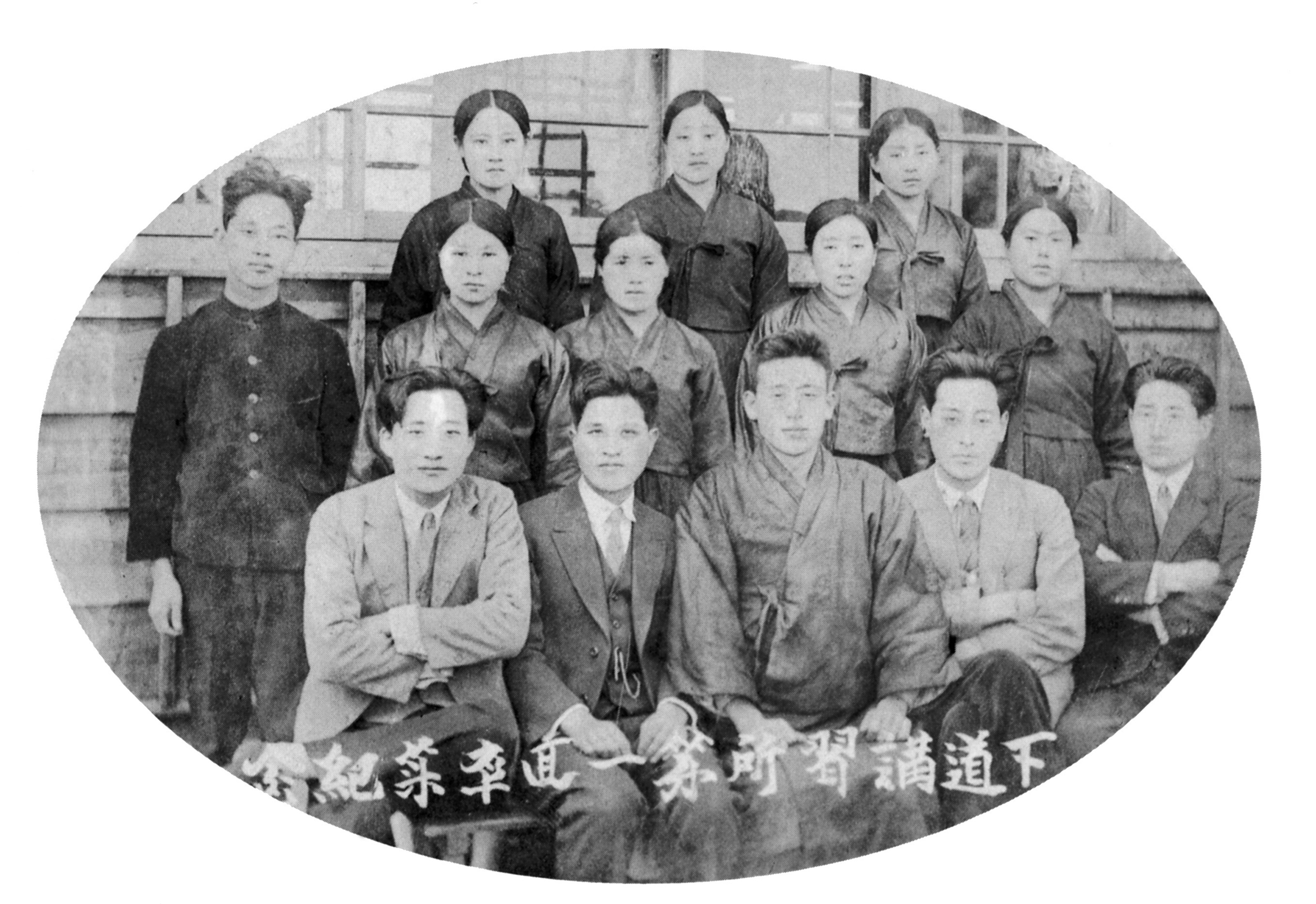

[The first graduation photo of the Hado Night Study Center: The five main actors of the Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement, including Bu Chun-hwa, Kim Ok-nyeon, Bu Deok-nyang, Ko Soon-hyo (also known as Ko Cha-dong), and Kim Gye-seok, were all graduates of the first class.]

The 90th anniversary of Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement

During the National Liberation Day ceremony on Aug. 15, 2018, President Moon Jae-in mentioned the history of the 1932 Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement in his congratulatory speech. President Moon said, “In 1932, Gujwa-eup on Jeju Island was the epicenter of the female divers’ anti-Japanese resistance, which was sparked by five divers: Ko Cha-dong, Kim Gye-seok, Kim Ok-nyeon, Bu Deok-nyang and Bu Chun-hwa. The anti-Japanese movement spread among 800 female divers, and approximately 17,000 women participated in 238 rallies in total during three months. Now a monument to the Jeju female divers’ anti-Japanese movement stands in Gujwa-eup.” He also said, “Any endeavor made for liberation will certainly be given due credit and legitimate esteem. The government will identify more accounts of the independence movement without discrimination on the basis of one’s gender or role. I believe that the complete identification of the independence movement’s unknown history and independence activists will be the consummation of yet another liberation.”

The 1932 Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement is a people’s movement that holds an important position in the history of the anti-Japanese independence movement during the Japanese colonial era. Above all, the movement is unique in that the main agents were female divers. It is the largest anti-Japanese movement to take place on Jeju Island during the Japanese colonial era, with some 17,000 people participating, and at the same time, it is the largest fishers’ uprising in Korea. It is also evaluated as an organizational anti-Japanese movement that had an organic connection with the youth social movement in Jeju.

Under the anti-communist regimes, which caused the collective deaths of tens of thousands of residents during Jeju 4·3 and its subsequent suppression, the haenyeo struggle was long regarded as an impure movement connected to socialist activists, where the main actors of the struggle were suppressed. The memory of the fight for national independence had been hidden. Local historians shrunk the memory of the haenyeo struggle by documenting the case merely as a movement of haenyeo to protect their livelihood. The memory of the haenyeo struggle was returned to its rightful place as a result of the liberalization and democratization of Korean society.

The memory was handed down as an official one in such efforts as the compilation of The History of Jeju Anti-Japanese Independence Movements and The Annals of Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Struggle, the construction of the Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement Memorial Tower, the creation of the Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement Memorial Park and the Jeju Haenyeo Museum, the hosting of the commemorative ceremony for the Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement, and the erection of a bust of the main actors.

The Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement was an organized and systematic struggle against economic discrimination, exploitation, and oppression by the Japanese during the harsh Japanese colonial era. The movement went beyond the boundaries of the haenyeo community to receive support from other Jeju residents, developing into an islandwide movement.

The Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement was revived as a historical memory during the Jeju 4·3 resistance following liberation. Newspaper articles conveying the public sentiment of Jeju residents at the time of Jeju 4·3 described the resistant atmosphere against the tyranny of external forces, represented by the Northwest Youth League and their supportive police forces, by comparing it to the haenyeo struggle against Japanese imperialism.

In marking the 90th anniversary of the Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement today, Jeju residents stand in another place demanding a transition of the times. It is necessary to reflect on the historical significance of the resistance movements in Jeju, which have striven to protect the self-esteem and identity of the community through the Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement and Jeju 4·3.